Being John Malkovich At Twenty-Five

Spike Jonze's film was released in October 1999; here are contemporary interviews with Jonze and co-producer Michael Stipe

Two interviews from the 1999 release of Being John Malkovich, with co-producer Michael Stipe and director Spike Jonze. A shorter version of the Stipe interview appeared at the long-defunct Playboy.com, editor, Rob Walton.

Michael Stipe comes into the interview suite balancing a plate with an omelet and hash browns just like hotel room service. He’s missing only a small flower in a small vase. Which, of course, it was, as he was a little late to talking, as a co-producer, about the imminent release of Being John Malkovich, another bloom of indie moviemaking in that halcyon year of 1999.

While Stipe's published books of his photography, he is, of course, best known as the frontman for R.E.M. But for most of the last decade, he's also quietly gone about a mission of changing the face of American movies. As a producer, he's put his interests and time behind projects both large and small, such as the shockingly funny documentary on no-budget filmmaking, American Movie.

But his biggest splash so far is Being John Malkovich, the surreal, subversive comedy of what goes on in the minds of those who wonder what goes on in the minds of celebrities, written by first-timer Charlie Kaufman and directed by video wonder Spike Jonze. Being John Malkovich takes chances, starting with its nutty concept, its casting-against-type (John Cusack as a sniveling puppeteer; Cameron Diaz made ordinary as his unloved wife) and working through to its weird and farcical conclusion. It's filled with the kind of artistry that doesn't come from formula.

Go ahead, have a bite of that omelet.

Stipe smiles.

Thank you. I was going to smoke instead. I went all day yesterday with three shrimps and half a tuna-fish sandwich.

What prompted you to produce?

I’ve been working in film for twelve years, which most people don’t know. Um. Probably the only thing I’ve worked on that came out with something of a wide release was Velvet Goldmine, two years ago, the Todd Haynes film. But I’ve done six feature films.

I heard you had an interest in American Beauty.

That was my movie! Seriously, I wanted that script. I thought it was great. We wanted to make it, but we were outbid.

What attracts you about movies as a medium?

Like music, it’s a very powerful medium. I’m drawn to it. I’m a photographer myself, and I have a lot of friends who work in the film business. The first movie that I executive-produced that really went wide was Velvet Goldmine. Most of the stuff I've done is really under the radar. I’ve garnered a good deal of experience working with films like that, and I'm continuing to do so.

What about this project made you say, “I wanna do this”?

Stipe shrugs.

I read the script! I read a lot of scripts and there's such so much dreck. When the main character or the supporting character isn't an out-of-work script writer, I'm amazed. There are so many horrible, horrible scripts floating around. Some of them have the spark of an idea or the spark of a character that's vaguely interesting but they never, ever carry through. But this script came and [my producing partner] Sandy Stern said, “You have to read this [now.] So I read it and finished it at 2am in Athens and called him 11pm L.A. time and said, “Make the call tonight, we have to make this movie.” The script had been around Hollywood for several years and a lot of people had read it and thought it was funny and audacious. But I no one had the audacity to make that call until we got it. Sandy flew to New York and met with Charlie Kaufman, then we found out that Spike Jonze had also read it and liked it. He was working on “Harold and the Purple Crayon,” but that never happened. So we put a little team together, started going over the script, making it happen.

The script is throwing up gender, throwing up identity, throwing up ideas of the soul. The late twentieth century has had us moving along the separation of mind, body and spirit. But I think people are slowly heading towards something else.

Was it always John Malkovich?

Yeah. The short list of alternatives was really dire. And Charlie can't answer “Why John Malkovich?” For whatever reason, he always just shrugs his shoulders. There is really no one else who could have pulled it off.

So if Malkovich hadn't agreed to do it, you’d have been in trouble.

We hade a short list of "What if Malkovich is horribly offended and wants to sue us?" and "What if he says this is a crock of shit and I want nothing to do with it?" Who else could do it? It was original enough of an idea that we could have tried to insert someone else but I don't think it would have worked.

There’s a Steve Buscemi rumor.

Buscemi would be okaaaaay. But there's something about Malkovich that's more than his public persona. Which he so brilliantly sends up, and that takes, I'm sorry, that's a lot of balls to really send yourself up like that

Did Malkovich accept it immediately?

No. he read the script five years ago when Charlie wrote it, just because it had his name on it. He thought it was curious and terrifying. But it took Spike going to visit him in France (where he lives) to convince him that as a director, he'd be able to follow through and make something as smart as the script.

Who came on board next?

John Cusack was next... or was it the other way around? Then Catherine Keener and then Cameron [Diaz]. Even with that cast, we had difficulty finding financiers.

What does the script say about a culture of celebrity?

To me, Craig's line, “This is a metaphysical can of worms,” says it all. The script is throwing up gender, throwing up identity, throwing up ideas of the soul. The late twentieth century has had us moving along the separation of mind, body and spirit. But I think people are slowly heading towards something else. To be able to present a script that all these as underlying themes, and not smack you in the face with it is great. The script isn’t didactic, it's very funny, it's surreal and bizarre.

Would you call it philosophical, then?

Philosophical, yeah, but I think Spike downplayed a lot. If you think about the way this could have been shot, directed and acted, it could have been a lot more gratuitous. He was really brave to play the humor really flat and allow the surrealness of the story to become ordinary.

Basic question: what would it be like, whose head would you go into if you had a “portal”?

The scene where Lottie and Maxine are being chased through his subsconscious. it’d probably be not dissimilar to that.

Anyone whose eyes you'd like to see through for fifteen minutes?

I feel like I do, so I don't need a portal. I don't feel like I need a portal to see into people's heads. It's not that hard!

Is the film as good as it seemed it could be on the page?

Oh, yeah, it's better. I knew how Spike envisioned it, but I didn't imagine he'd take it as far as he did. It's not sight gags. It was all about subtleties and downplaying the surreal twists and turns of the story. Think about the Jim Carrey movie, [The Mask]. This movie’s gags could easily played out like that, visually. Catherine played this very subtly. As Cusack said, in her character, he always felt like the mean thing that she said to you would be the last mean thing she would ever say and from that moment, she'd become nice. That's a very subtle thing for an actor to do and she did a great job of it. And this thing between Keener and Diaz hasn't been successfully done [since Hotel New Hampshire] between Jodie Foster and Nastassja Kinski when the roles they played were the opposite of the roles they would have played had the male studio system been dictating who was going to take what role.

How long have you known Spike?

I've known Spike for 12 years. I met him through Jane Pratt when she was doing Sassy magazine. and they were working on an adjunct to Sassy, a boy version called Dirt .

Is the movie business or the music business more treacherous?

That's such an easy answer. Film! Hands down. The music business is a walk in the park, because with MP3s all you need is a tape recorder and a guitar.

Any interest in directing?

No. None. No desire at all. I know directors who wake up in the morning and they see movies in their head and it's their place in life. I'm 39 and pretty much I've made my mark in music and I've had an interest in film since I was 22 and I've been a photographer since I was 15. Those are my three creative outlets.

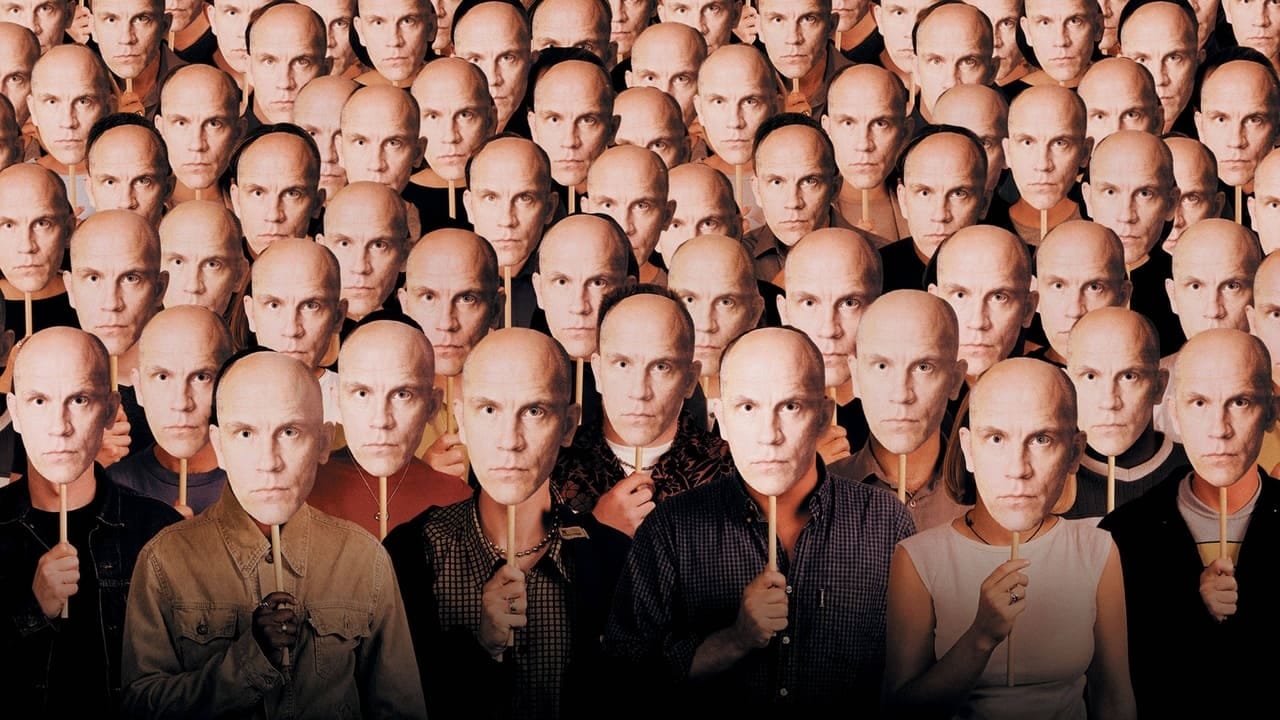

The scenes when Malkovich goes into his own mind are troubling, and, so is the end where Malkovich becomes a conduit for dozens of souls.

Yes, the woman on the piano is terrifying. I thought both scenes were brilliant plot twists and a fine ending for a film. It begs the questions, “What are we? who are we? How separate are we, one from the next, questions of gender, questions of identity?” I am hoping this film puts a few more chinks in the armor that is the studio system

There was a point in the early nineties, where I'd been working on very, very guerilla independent films for a couple of years. Then I wanted to go Hollywood! I knew a lot of people who were just incredibly frustrated with the material that they were offered as actors or directors or editors or writers or lighting poeple or what have you. Naively, I thought, well, I’ll just create another film company that will make movies that don't suck. It's just as easy as that.

So most movies suck?

Yes. I was on vacation in Athens for a week, having just come off tour on my band before I had to come up [to New York City] for this thing, and I really just wanted to just relax and go see movies with my friends. With all the multiplexes in Clark County, Georgia, out of thirty-five-odd films playing, I couldn't find one fucking thing worth seeing that I hadn't already seen, which was about three of them. I thought The Sixth Sense was wonderful.

So "Being John Malkovich" counts as going Hollywood?

This is it. This is my Hollywood. How d’ya like it? This is it.

Did you know Mlakovich before?

We met after this proect. Actually, we spoke on the phone years ago. I walked into my house after a fact-finding mission to South Ameirca and the phone rang. I picked it up, it was John Malkovich. I was asking him to this charitable, human rights thing, which he declined. But we met through this project. I don't call that a relationship— refusing a phone call! But it was my brush with the greatnesss taht is Malkovich.

Did you ever consider a backup celebrity if Malkovich wouldn't do it?

No. There's nobody else who really could have filled that.

Why?

Y'know, I can't say. And honestly, believe me, we had a short list of "What if Malkovich is horribly offended and wants to sue us?" and "What if he says this is a crock of shit and I want nothing to do with it?" Who else could do it?

So it’s just Malkovich.

I think just in terms of this pr4ojecxt, Malkovich is one of the few actors who is secure enough in his own body of work and his own abilities to send himself up in such a grand way as he did in this movie. And clearly, the character he's playing on film is supposed to be himself as a character—extremely arrogant, extremely egotistical, extremely misogynist… weird. But that's not John Malkovich.

If you sent yourself up, but musically, what would it be like?

It would be not unlike some version of this film with the Spice Girls. I would go for the biggest buck. I would probably hire teenagers to lip-sync along and disguise my voice so it's not Michael Stipe. I would hire beautiful young teenagers and strap them into latex and put them on stage.

The Spice Girls?

Stipe smiles.

I wouldn't do it. I would key into whatever was the next coming musical thing and do that.

John Malkovich: At home, he's a tourist: Fame is pain and fame is confusion.

That's one of the underlying messages of Being John Malkovich, an insane premise for a movie developed with dear, cracked illogic. It might be brilliant or a masterpiece; the likes of Esquire magazine have already anointed Spike Jonze's direction of Charlie Kaufman's inspired screenplay with those dangerous encomiums.

A terrific shaggy-celeb fable, Being John Malkovich develops and elaborates on the rules of its world with uncommon diligence. In contemporary Manhattan, Malkovich plays "himself," a deracinated version of a celebrity of whom everyone on the street can (and will) recite the same handful of sloppy factoids. John Cusack is Craig, a greasy-haired, rotten-hearted puppeteer who wants to crush a world that doesn't appreciate his genius. Cameron Diaz, under a mud-and-stick-colored wig, plays Lottie, Craig's animal-clutching, love-starved wife. And, as the lust object of most of the movie's men, the always wonderful Catherine Keener makes hay with her particular beauty (and just a dollop of extra cerise lipstick). One day, Craig makes a discovery behind the filing cabinets of the odd office where he works—a portal that allows entry into the mind of John Malkovich. After fifteen minutes, you're ejected into a muddy ditch alongside the New Jersey Turnpike. An entrepreneur is born. Who wouldn't want to be someone else for fifteen minutes?

Director Spike Jonze restrains his rambunctious rock video-trained eye and conceptual swagger to serve Kaufman's script. Rules are established, genders are bent, the idea of becoming "someone else" is more frightening by the moment. It's a different can of existential worms than, say, King of Comedy, wherein Jerry Lewis' talk show host reflected his own notorious prickliness as well as Johnny Carson's cool reserve. Malkovich is playing an idea more of celebrity, of elevated existence, than any reflection of whatever may go on in his head. Try not to hear too much before seeing the movie: I'll just mention that when Malkovich attempts to take the trip into his own head, he disguises himself as a tourist, with an I Love N.Y. cap pulled down over his expansive brow.

Jonze, 30, born Adam Singer, is widely admired for his video and commercials work, but he's not known for long moments of introspection. (He makes his big-screen acting debut this fall as well, in David O. Russell’s Three Kings.) While Kaufman's script had made the rounds for almost five years, Malkovich committed to the film after Jonze visited him at his home in France. "We didn't have to pitch it or anything. He read the script and he liked it for the same reasons we all liked it. It's funny, it's original. Y'know, complex character and relationships. He just had to figure out if it was something he really wanted to do or not. There wasn't anything we could say or do, he just had to say yes or no."

The film is as twisty as anything out there, and it's not a one-joke twist, like certain surprise endings that have made a mint this year, or the "discovery" in The Truman Show. Jonze hopes there are a few surprises for audiences after the first weekend. "I love watching movies where you don't know too much about it."

"I dunno," he says, pausing for a while again.

For someone whose work hadn't demonstrated knowing too much about directing actors, there's a consistency of tone that impresses. Probably the greatest challenge was how to direct someone playing a version of themselves. "Yeah, yeah," Jonze agrees. "It's like, 'John, you're not getting the character right. Malkovich would do this.' All the scenes with Malk where he was playing Malkovich, we talked about him as a character. So, John, this Malkovich thinks of himself as a lover and a ladies' man.' He'd just laugh and say, 'OK.' He read the script so he knew what was up."

So the movie went according to plan? "I dunno," he says, pausing for a while again. "Overall I wanted things to be played like Charlie's writing, you can enjoy on a lot of different levels, the comedy, these really interesting ideas, these characters and these relationships. Playing those as our priority in terms of the acting, the art direction, the music, the wardrobe, and just play these characters, these people. All the other things, the ideas would be that much more interesting and the humor would be that much more fun."

Did he miss all the toys from his other work? "Um. No. I think there are certain scenes that required more complicated camera stuff. For the most part, we only had a certain amount of time to shoot the movie, and we had to make sure everything you were going to spend your time and money you really wanted and needed."

Jonze thinks for a long time when he's asked if his first feature held any surprises. "I dunno. It turned out basically... um. Everything changes in preproduction, casting, the script, all these little things keep developing, yet it turned out overall the way I wanted. It's the small stuff that changes."