Brooklyn is flooded. The mayor is absent. Chicago plans to place Latin American asylum seekers thrust onto buses and trafficked north by Texas’ lycanthrope governor into tent refugee camps. The governor says, not so fast.

That’s just notes from the past few hours, this Friday at the end of September 2023.

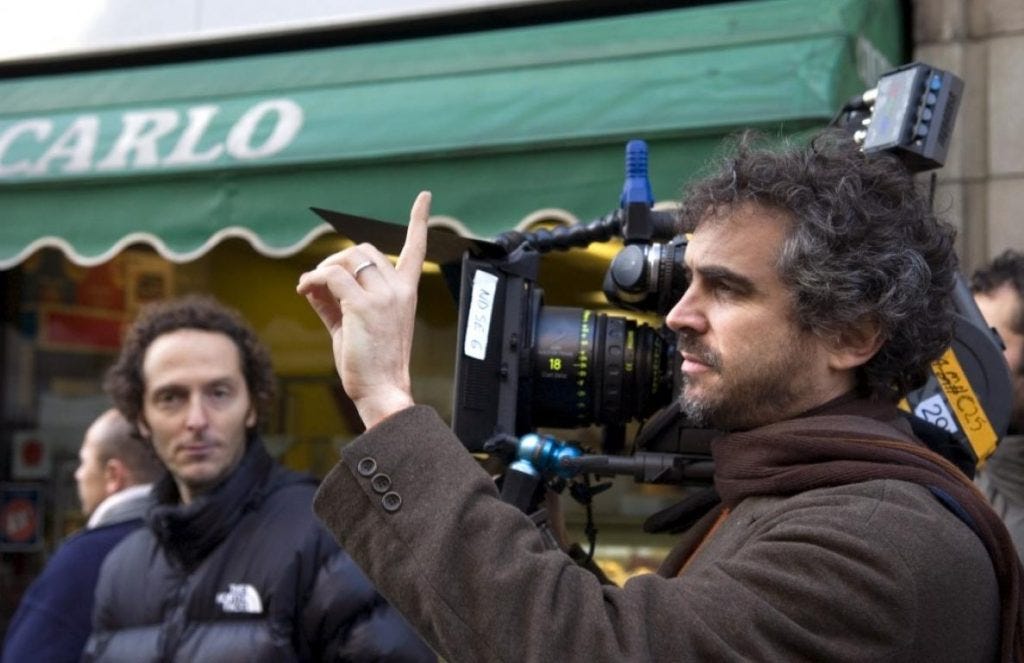

A couple years back, tough-minded, big-hearted advice columnist Heather Havrilesky found a moment, another moment that recalled Alfonso Cuarón’s bruising, bruised Children of Men. The film “gives you such a visceral taste of ambient desperation and resignation and this sad, frantic search for meaning. It's such a brutal movie,” she wrote. “It springs to mind all the time for me.”

Doesn't it?

For a possible revisit of the movie, I dug up the extended transcript of an interview I had done for long-gone movie website The Reeler, with Cuarón, to reflect upon the virtues of his dour, detailed masterpiece, and see how it met the next, decidedly malefic downturn in how the United States treats stolen children. But bad things happened in batches. Then other bad things happened on the way to today: the arrival of the virus, restrictions, shutdown, lockdown. Fires, floods. Overflowing “entrance cities.” Heat. Crop-killing heat. Mass migration. Militarized cities. Training grounds, “cop cities.” Further floods.

We live here now.

Cuarón's Christmas 2006 feature is monstrously alive to the condition of despair as well as the necessary dogged march forward. Cuarón consulted a raft of futurists to game a damnable future, his 2027, and the backdrop seethes with detail. Like his other films, including Roma (2018), Children of Men is concentrated cinema, wrought, focused, emblematic. They don’t make movies like this any more, not that any movies are being produced right now at all. Cuarón, I rediscovered, was equally concerned with the survival of richly detailed cinema as the fraught voyage of his encircled, besieged characters.

Silent cinema achieved an amazing mastery of communicating without language.

Cinema caught up, but with the arrival of sound, it became about people

talking and telling stories and singing.

Masquerading as a science fiction film, Children of Men is set seven years from then, and now a decade ago, when, for reasons never known, after wars and disasters and plagues, women worldwide are no longer able to conceive. In its quietly bravura opening scene, Theo (Clive Owen), an alcoholic onetime activist, witnesses a crowd in a café weeping over television news coverage of the death of an eighteen-year-old—“the world's youngest person.” A few seconds later on Fleet Street—a London with grit but without glamour, dirtied as if by another century's version of the Blitz—a terrorist bomb detonates. Julian (Julianne Moore), a former lover, turns up, dragging Theo into a battle for the future of the other failed, failing cities; he must protect a female "fugee," a woman (Clare-Hope Ashitey) who is unaccountably pregnant, on her way to sanctuary. Does the government want her dead? What of the masses of angry anarchists?

As intimate as Cuarón's earlier, more conventional road movie Y Tu Mamá También (2001), Children of Men is enriched with elegant metaphors for how countries and their ideologies shape how immigrants and refugees are treated in Europe and the United States. (It also boasts a witty, reflective subplot with Michael Caine as an old friend, who, in his forties way back in the early 2000s, had protested British involvement in the first Iraq War.) Cuarón is cerebral yet still emotional; Children of Men is keenly close to silent cinema, with geometry and décor of uncommon precision, occasional explosions and an appreciation of the traveling shot that would please Max Ophüls. The feeling is both hyperrealist and nightmarishly impressionistic: a kind of lucid screaming.

Children of Men is a great film that gets better every year. If I was Alfonso Cuarón I'd just be tweeting 'Told ya' every fucking day.

— u13 (@utherlives) October 10, 2019

There is a welter of eminent influences, borrowings and outright lifts in Cuarón's arsenal. I had movies in mind: the urban verisimilitude of CIA-taught terrorism thriller The Battle of Algiers (1966); master shots reminiscent of Erice’s oneiric Spirit of the Beehive, (1973); a city as blasted as Kubrick’s vision of Brit-shot Hue in Full Metal Jacket (1987); the melancholic romantic perfection of Murnau’s Sunrise (1927). Was there a single movie that he, as a cineaste and cinephile, he would describe as perfectly achieved in every fathomable fashion?

Cuarón cut a big grin way back then. "Oh, I have a bunch of them," he said. "I am almost afraid to say, then you have to keep on going! No, that's the beauty of cinema, man. There are amazing masterpieces. I am almost afraid to unleash the demon. Your interview is going to be a laundry list of amazing films. Completely, fully fulfilled. I'll say just Sunrise." Indeed, I said, there are hints of city-versus-country in Children of Men that gain from comparison, and the film's climax would be unthinkable without the German director's example. He laughed. "Man! You know Sunrise! That's good."

How about Battle of Algiers? "Well, okay, so you see where I rip everything off!" he said. "That's good! I love Battle of Algiers! That was a big point of departure. But it's different; Pontecorvo was honoring the technology of his times. It was not handheld, everything was kind of stiff. Funny enough, it was very stiff, because of 35mm cameras and pretty much on tripods. We were trying just to take the same approach but as with the technologies of today. We shot in 35, but with the mobility of a video camera."

With the forceful production design that is rich but not slick like a page from a furnishings catalog, Cuarón's decors tell the story, too, and better than a few reams of dialogue. Children of Men demonstrates that the director wants to tell stories by the way people live and move in their spaces—the contents of the frame are transparent, but they hold weight. "Narrative is the poison of cinema,” he said earlier. “What I hate is when cinema is hostage of narrative," Cuarón told me. "Then I say, 'Come on—don't be lazy, read a book.' If you want to see performances, go to the theater; it's fantastic! It's an actor's medium there and a dramatic medium—at least conventional theater. But come on, leave cinema alone! Let cinema breathe, in which narrative is an element of the cinematic experience, but it's an element, as acting is an element, cinematography is an element. Music and decors, those are elements. But right now? Cinema becomes just about seeing illustrated stories as opposed to engaging audiences in an experience in which you don't explain much.

People tell you that narrative is something organically human.

Yes. But even more? The reading of symbols.

Even what you see in the early paintings in caves.

"I'm not saying that narrative isn't valuable, of course. But it's not only in cinema. In our culture, this culture, it’s over-narratized. Everything is built on the content of a narrative. Politicians tell you narratives all the time. Then we are missing one of the biggest, probably something more powerful than narrative to humans, that is, symbols. The reading of symbols. Not only the understanding of narrative. People tell you that narrative is something organically human. Yes. But even more? The reading of symbols. Even what you see in the early paintings in caves. Yeah, there's a narrative there, but more than that, there's movement. And there are symbolic elements that they were relating. It's not like they did a comic strip of what happened with hunters."

Cuarón doesn't aim to simplify, however, working instead to maintain his struggle to be as concrete as possible yet remain enigmatic. Yes, like a silent movie. He invoked his compatriot and friend Guillermo Del Toro's Spanish Civil War fairytale Pan's Labyrinth (2006). "In Guillermo's film, you follow story, you follow psychology, but what really matters are the thematic metaphors he's working with all the time. It's something that cinema—particularly silent cinema—had so strongly before the big explosion—the big September 11 of sound—happened to cinema! They achieved an amazing mastery of communicating without language. Cinema caught up, but with the arrival of sound, it became about people talking and telling stories and singing.

"It's so damn gratifying," Cuarón continued. "The principle of cinema is that you are looking at that screen. A lot of reviewers nowadays, they fall into that vice: they want stories. They want explanations, they want exposition and they want political postures. Why does cinema have to be a medium for making political statements as opposed to presenting facts, presenting elements and then you make your own conclusions—even if they are elusive? There's nothing more beautiful than elusiveness in cinema."

The $76 million-budgeted "Children of Men" was released December 25, 2006 on sixteen screens, widening to 1,524 locales. Theatrically, it grossed $33.5 million in North America and $34.5 million in the rest of the world, taking $69 million before descending to the accounting department. "Children of Men" is available to rent on many of the usual providers.