David Fincher In The Panic Room

"It's like the high-school play. It's like eight fucking people and that's it, that's all you got."

Rumors circulate again about an unlikely remake to kick off David Fincher’s latest three-year stint with Netflix. After the critical conflagration of Fight Club (1999), Fincher retrenched with a precise exercise—much like The Killer after Mank—that functions as the full Fincher as well. (“It’s not supposed to be that important,” he says with his standard verbal shrug in the film’sDVD commentary. “B-movies are kind of, in a weird way, the most memorable movies.”)

We talked about The Panic Room before its release in 2002 in a large, unfurnished room in a Los Angeles hotel, with sheets of opaque plastic covering one wall and its wide windows to the west toward the sea.

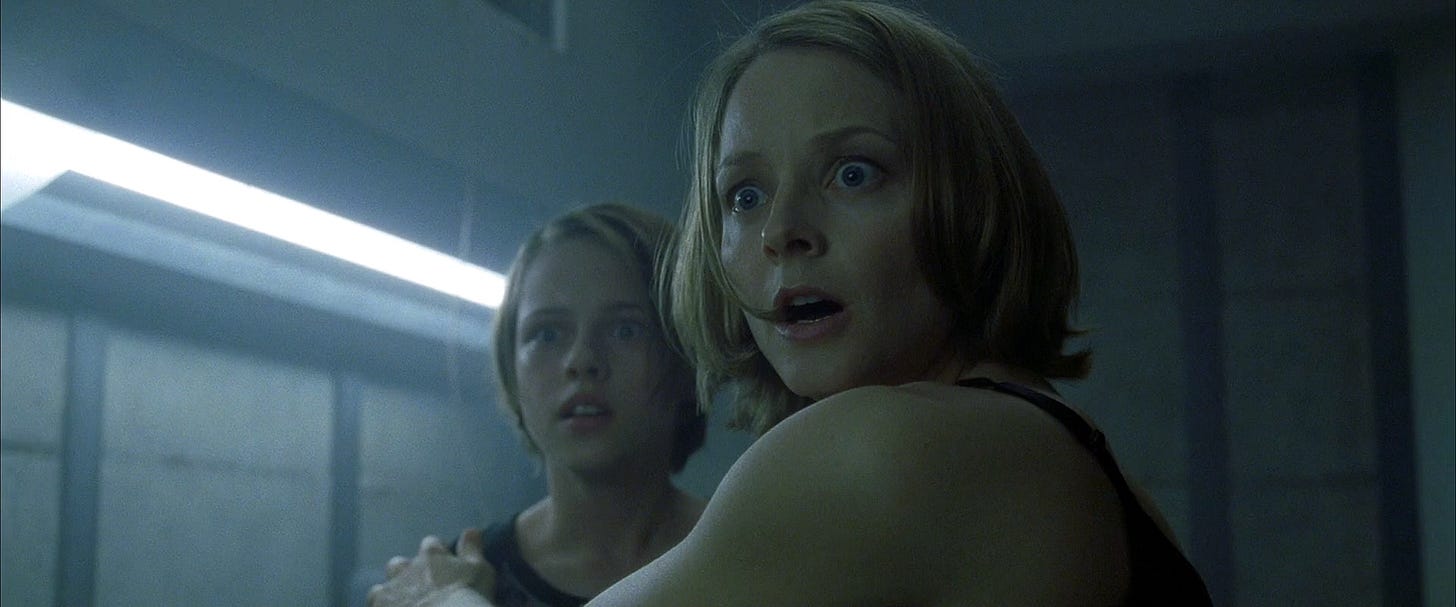

Hearing about Panic Room, a script by David Koepp bought by Columbia Pictures for several million dollars, my heart sank. One location, one night, one goal: a divorced mother (Jodie Foster) must protect her daughter (Kristen Stewart) against home invaders (Forest Whitaker, Jared Leto, Dwight Yoakam). Her greatest weapon? A secret, cement-lined, steel-reinforced "panic room" hidden in the middle of the house.

No need! Panic Room works like the scare machine it needs tobe. Jodie Foster took the role after Nicole Kidman was injured following several weeks of shooting, and her pain, then courage, as the put-upon mom is one of her most meticulous performances.

Fincher plays at soft-spoken, but talking to him about the production of Panic Room reveals him as meticulous about any detail you could bring up. I mention my fear before seeing the film that he wouldn't pull off this hyperkinetic, fast-as-the-wind riff on Hitchcock's Rear Window.

FINCHER: Yeah. That was the key to making it. It's a pretty terse script. There's not a lot there. The whole time, it was like, y'know, an hour-and-forty-five-minute movie, that's what it's gotta be. It's got to feel like one night. Is it going to feel like that or is going to feel like three nights?"

There's hardly any backstory for the characters. We're in the present. How long is this woman in the house before hell breaks loose—four hours?

Yeah. Not even. That's the thing. That's what makes it a movie. We kept saying, [taking a major scene from the film] there's no way you're not going to see fucking fire on the ceiling in the trailer. So all this playing coy in the first three pages, it's stupid. It's like, let's get on with it. We know where we're going with it. We know where we're going to wind up.

The movie's beautifully dark—gray and blue and black.

It seemed like if you were going to make a movie that takes place during a breaking-and-entering in the middle of the night, it's gotta be dark.

The dialogue avoids catchphrases, unlike nineties movie heroes were fond of cracking, as well as overt racial remarks. Whitaker is black; Yoakum can be taken by some as being poor Southern bad guy; Leto is a spoiled Manhattan trustafarian. There are a handful of pop-culture jokes, but nobody's slanging about class or race or gender up front.

I think we added one line in the looping. You can't really hear it because there's so much music and craziness going on. But in the scene where you see the fight through the bedroom doorway and you see it in shadows, I had Forest say, 'Get off me, you crazy hillbilly motherfucker!' But again, New York, I don't see racial divisions in New York. Everybody's suffering the same and everybody's pawing their way. The most agonized and miserable guy in the movie is the one with the trust fund!

The script can mostly stand as a paradigm of classic Hollywood terseness, where you can say almost nothing yet say everything.

David's a real stickler for, tell what you need to know at the last possible minute. I'm sure in the second Jurassic Park that it was not David's decision to show that Jeff Goldblum's daughter is a gymnast in the first act. That's just not who he is. This is a movie-movie.

Fincher pauses, reading my page filled with scribbled notes and diagrams upside-down.

It's about what the expectations are about movies as much as our expectations about people. In that sense, it is a true genre picture. It exists to either deliver or subvert your expectations of what's going to happen in that situation. It's a crime thriller, but it's also in the Treasure of the Sierra Madre vein. These people are going in to look for what they perceive as the quick solution to their problems. Money is never the quick solution to anyone's problems. It's just an object that everyone's after for the wrong reasons. It's a cinematic study in how you use or abuse the one setting for maximum effect. I was drawn to it because I loved the idea: They've gotta get in, they've gotta get in, now how are they going to get out? A simple reversal.

The story's so stripped-down that it can be read as a really clean metaphor for child custody battles.

This is a movie about divorce. The destruction of the home, the attempts to... One party's always after the money, the other party is going to allow whatever has to be destroyed to be destroyed, whatever. That's there.

Get in, get out, survive, vanquish the bad guys. That's a pretty simple narrative mechanism after Fight Club. Was it time for a more direct kind of storytelling?

Fincher turned my notes around, not making them any more legible, then looks back to me.

I don't really think in those terms. I read a script, going, 'Is it a movie I'd want to see, A; are there a lot of movies like it already out, B; and do I think I can do something with it, C. That's my criteria. This movie's been a challenge for me because it's all in one night, all in one place. It's like the high-school play. It's like eight fucking people and that's it, that's all you got.

“Art of the Title” analyzes the memorable title sequence here.