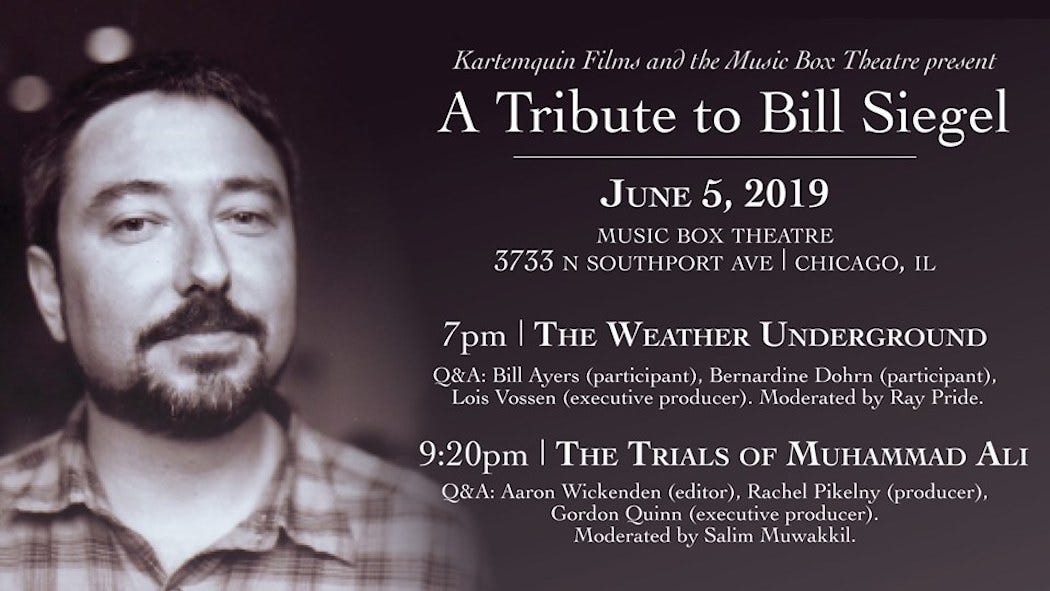

“Bill Siegel (December 24, 1962–December 11, 2018) was an American documentary film producer and director.”

I was making a list of who I would want to talk to if I were to compile an oral history that would draw on a certain passage of Chicago cultural time through the criss-crossing of a long-lived local tavern.

Looking around that room and thinking of what face stood where at what point across decades, one face I saw, laughing, teasing, in one or two chosen parts of that room across the decades was Bill Siegel, ready to talk about music, politics, musical, political radicalism, the necessity of being thunderstruck by a motion picture, of crafted nonfiction, an image, a sound, a lick. He was a curator and an aficionado and always unabashed.

He could have talked that book.

But he left six years ago.

After the movies at the Music Box that night, a couple of us talked about Bill. This is my piece.

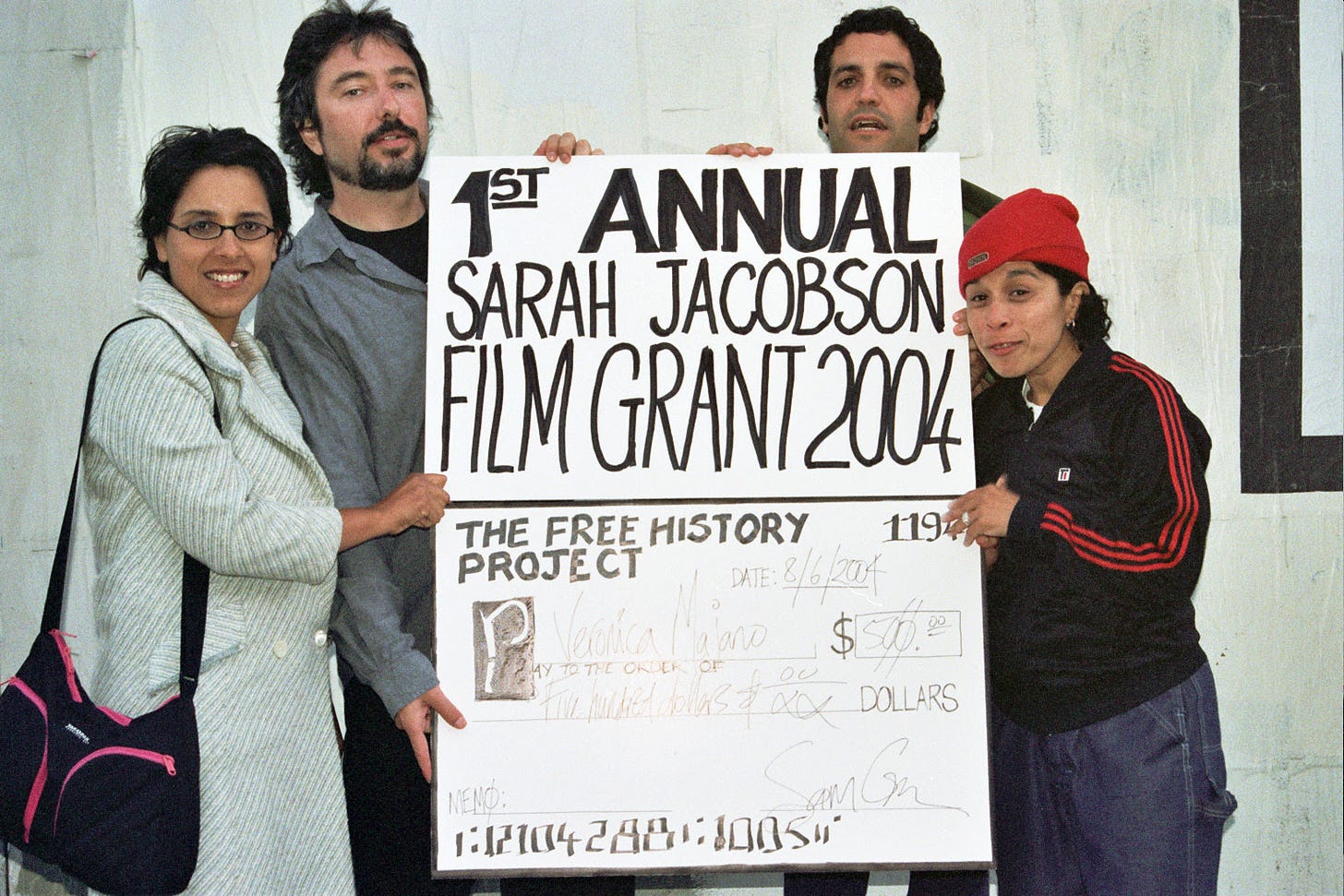

Sam Green, who arranged tonight’s 35mm print, sends his best wishes.

Bill Siegel worked for twenty years at Great Books, teaching educators. He left only two completed movies. But he taught ten thousand teachers. Fewer films, but more friends.

Friends, films, and here we are.

I saw Bill the Friday night before. He was presenting Glenn Silber’s The War At Home. It was the first time he and Glenn had ever met, but as he explained that night, it was the movie that around the age of 18 showed him how to proceed with his life. As an activist, a filmmaker, a Madison resident, as an observer of the world as it is, rather than how it is spooned out to us.

We saw each other a few times a year, hit-and-run moments that seemed as if the previous conversation had taken place only days earlier. That night, I still saw the young Bill, even though he was visibly distracted. Still, the alternately goofy and serious, intellectually voracious young man stood right there. As always, I assumed I would run into him at the right random time, again and again.

And again.

He would easily outlive me!

I assumed everyone had that experience knowing Bill: not compartmentalized, but attentive to what two humans could share in a few short minutes.

He dreamt quietly and testified loudly, followed by laughter. That’s the thirty-plus years of Bill Siegel that I knew.

I encouraged him to accompany Trials of Muhammad Ali to the documentary festival in Thessaloniki in the north of Greece in March. I knew he would like the festival staff and the locals in a city that I know well. We agreed that I wouldn’t tell him much about what I had in store, but that I would introduce him to people and places I loved.

Bill’s second day there was an off-day for him, and I had other business, but at the end of the day I discovered that a half-dozen places I had I intended to take him, he had already discovered.

He started at his hotel by the Bay with the view of Mount Olympus and he set out into this two-thousand-year-old city of a million and managed in a spreading circle to discover and meet so many people across late afternoon and into the labyrinth of night. He had already made his way into the graces of my friends.

I scowled at him reprovingly at first, but all he had to do was laugh at the fine absurdity of it all.

Giggle, really.

He had made home in a day.

On “The Trials of Muhammad Ali,” Newcity, November 2013.

In the many years I’ve known Bill Siegel, I can’t remember a time he wasn’t talking or thinking about Muhammad Ali. Working as a researcher on Leon Gast’s 1996 When We Were Kings, as well as other projects like the six-hour-plus Muhammad Ali: The Whole Story (also 1996) that involved the three-time heavyweight champion, the Chicago-based documentary filmmaker became an expert on not only his athletic victories, but his political activism and commitment. Siegel was Oscar-nominated for the 2002 film, The Weather Underground, which he and Sam Green co-directed, and that film is sharp about political engagement and conviction, about idealism and legacy. Working through several iterations of The Trials of Muhammad Ali, Siegel has arrived at a rock-solid portrait of Ali’s passions about faith and conscience, and makes a stirring case that his political legacy is more important, and will be more lasting, than his days in the boxing ring. A co-production of Kartemquin Films, The Trials of Muhammad Ali resounds with the man’s singular voice. The wealth of seldom-seen footage is consistently eye-opening, and the interview subjects include the now-reclusive Louis Farrakhan. Siegel cleanly explains the most common question about why he portrays the man this way: “Why another film on Muhammad Ali? Because no Ali film has deeply explored his exile years, his spiritual transformation and his impact on the world beyond the ring… It has tensions involving faith, race, duty, and identity. And when you personalize those tensions through the humanity of Muhammad Ali, it gives them depth and definition in ways that resonate now.”

A version of this review of “Weather Underground” ran during Sundance 2003 at Indiewire.

A convocation of documentary makers recently named Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine the best documentary ever.

What a waste of a perfectly good word! While Michael Moore’s gamesplaying as a political provocateur has its value in asking questions others won’t, and Nick Broomfield is maturing nicely into his own in-your-face style, what’s to be done about the old-fashioned narrative that tells its story cleanly and quietly and insurgently? (Even if it is replete with sex, violence and strident political extremism.)

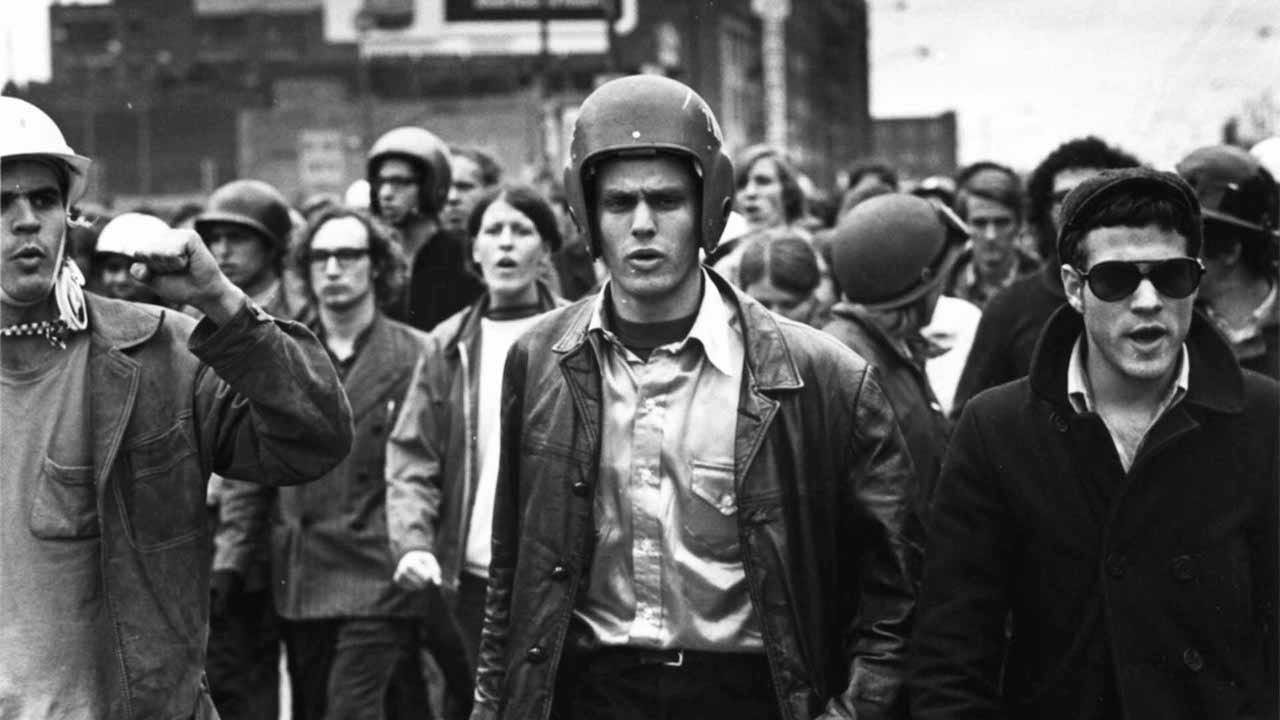

Weather Underground, by Sam Green and Bill Siegel, an impressively sturdy documentary about a difficult-to-master slice of American history, is a sweet rebuke to the narcissism-as-entertainment wing of contemporary doc-making. Its politics exists primarily in the choice of subject: a group of young people who bombed the U.S. Capitol. It’s thorny work, allowing the viewer to consider the ambitions and failures of the radical group, rather than a prickly irritation closer to monologue than investigation.

The feature-length, painstaking chronology, filled with interviews from former members, FBI agents, and adversal former colleagues such as historian Todd Gitlin, turns out to be more topical today than the filmmakers could ever imagined it would ever be, with the parameters of protest against a potential, unpopular war once again under discussion.

In October 1969, several hundred activists in football helmets, carrying baseball bats and lead pipes, wreaked forty-eight hours of mayhem, starting on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue, hoping to prompt a revolution against the Vietnam War and racism. A core group went underground, and battled the U.S. government, notably breaking Timothy Leary out of prison and bombing a range of federal facilities. (It prompted one of the largest FBI manhunts in history, which they evaded for years.) The Weather Underground charts both the ideas and outrage of the group in interviews with Underground members who have moved on to other careers, including Northwestern University Law School faculty member Bernardine Dohrn and her husband Bill Ayers, author of "Fugitive Days," a memoir of time spent underground. Ayers had the misfortune of a quarrelsome interview about the book appearing in the New York Times on September 11, 2001, and the backlash that greeted that bad timing is a model of how controversial ideas are received in larger media today.

But Weather Underground is, at least formally, an orthodox documentary, while testing the received wisdom of what is “acceptable discourse” in our land today. These were our terrorists, and the film also chronicles those who didn't make it back to the other side, including David Gilbert, serving a life sentence for his participation in a 1981 Brink's truck hold-up. What is most affecting, however, is seeing idealists in their fifties and sixties, who have made peace with their consciences, or have not, who have admitted to failures, or will not, yet carry the witness of experience about their failure utopia. “We fucked up” is the underlying refrain, but what was the failure? Did they fail American ideals? Communist or socialist ideals? Did they fail the revolution? All these morally ambiguous questions are implicit, yet the telling doesn’t seem to fall prey to a famous observation, sometimes attributed to Norman Mailer, that the man who remains a liberal is a fool.

It’s more commonplace than that: In its quiet, studied fashion, the ten minutes of interviews that cap Green and Siegel’s documentary suggest a universal truth. We all fail to be perfect, we fail our idealism, we fail history, all because we fail to be immortal. The film's most striking moment comes at the end when group member Naomi Jaffe, older, married with children, reflects the inevitable sorrow of a life long-lived. Her beliefs haven't changed so much as the times; if not for her family, she tells us, sure, she'd do it all over again.