Joshua Oppenheimer: The Beginning

An extended 2013 conversation with the articulate political filmmaker about The Act Of Killing

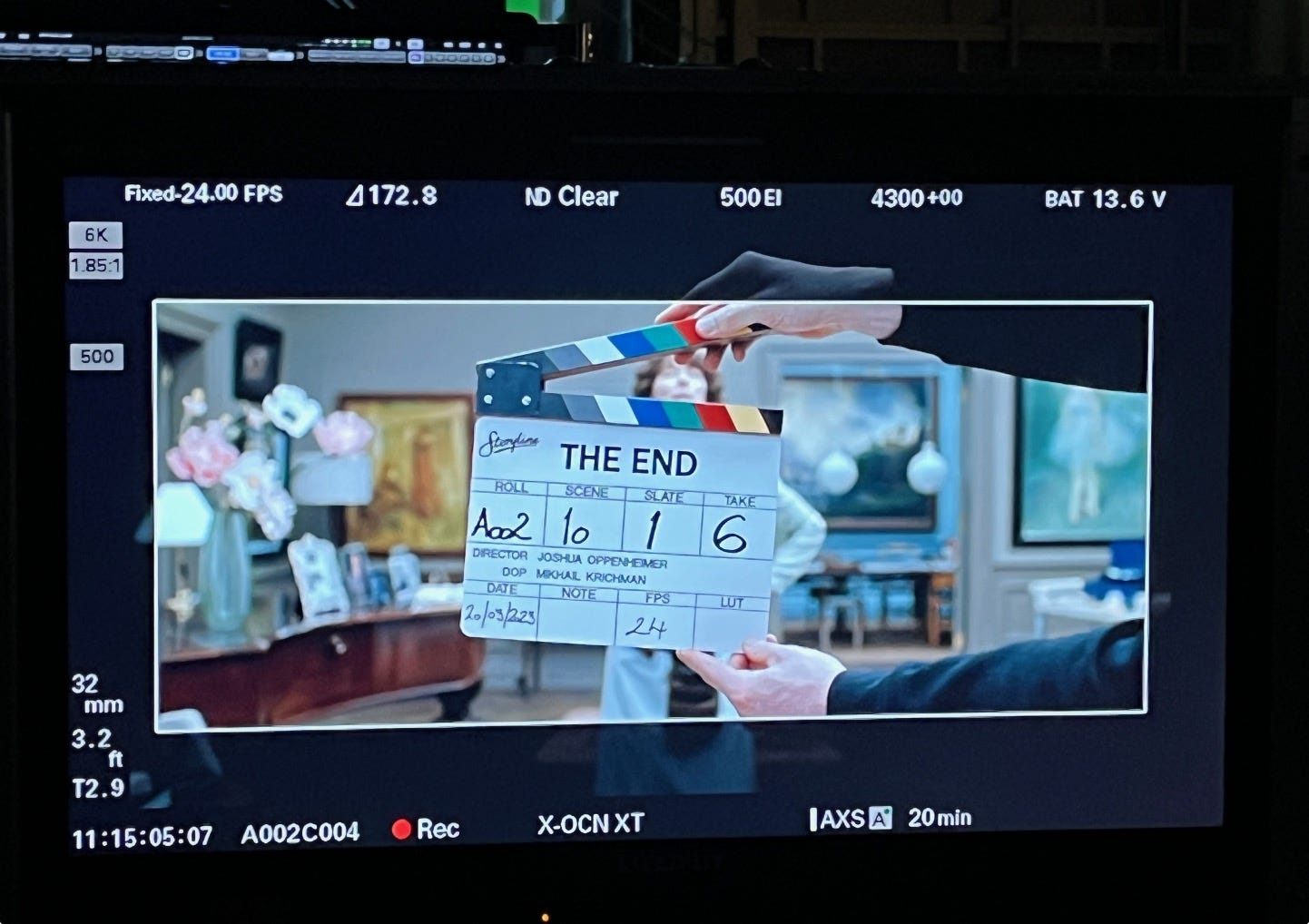

Joshua Oppenheimer’s years-in-the-making apocalypse musical The End debuted at Telluride 2024. NEON will distribute in the U. S. later this year. I spoke to Oppenheimer before the release of The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence; both were Filmmaker magazine cover stories, edited by Scott Macaulay and Vadim Rizov. This is a slightly edited version of the 2013 conversation about The Act Of Killing, which is streaming on Netflix, Peacock and other services. (Our 2015 conversation about The Look of Silence is behind the Filmmaker paywall here.)

When the government was overthrown by the military in Medan, Indonesia in 1965, Anwar Congo was one of many small-time gangsters who hawked movie tickets and plotted petty crimes in front of cinemas showing American movies. He and his buddies who translate "gangster" as meaning "free men," were enlisted as death squads—the Communists cut off imports of American movies like their beloved Elvis Presley musicals—and more than a million intellectuals, ethnic Chinese and alleged Communists and leftists were murdered. The "Medan Cinema Gangsters" were always eager to dance across the road to garrote an alleged Communist or "leftist" or two.

Deep into their seventh decade of life, these unrepentant men remain celebrated as heroes by their neighbors, on television talk shows that sound like cheery Nazi broadcasts, and by the paramilitary groups that keep a boot firmly on the neck of protest even today. In Joshua Oppenheimer's unique, incessant hallucination, a fantastical and horrifying hall of mirrors, Anwar and his friends are encouraged to revisit their acts of killing through recreations in the fashion of their favorite films. Will these fictional "acts of killing" prompt any kind of reflection by these hardened, cheery braggarts?

Plus: this punchy, audacious masterpiece is also a stylized musical, and a comedy, combining bruising horror and burlesque, neighborly genocide and the banality of vanity. Would you expect these "free men," proud, aging gangster-murderers to join in a production number of "Born Free" in front of an epic waterfall, surrounded by dancers in hot-neon-pink spangles and sung by a chorus that remains anonymous (like most of those credited at film's end) for their own safety?

Werner Herzog and Errol Morris signed on as executive producers late in the game, and The Act of Killing shares the wide-eyed ethnographic stare of Herzog and the driven processes of Morris, but Oppenheimer also revels in wandering into the wilderness, akin to Apichatpong Weerasethakul's dreams-within-dreams-within-jungles, alongside an insistent, biting, ceaseless critique of post-colonialism, burbling beneath in a way that even Slavoj Žižek might admire.

Oppenheimer speaks in a swift river of substantial subtext as he unpacks the panoply of reflections and notions in the film, which he co-directed with Christine Cynn and a key "anonymous." Movies, violence, and the construction of self-image were on our minds, as well as why his jam-packed, years-in-the-making, two-hour provocation-cum-meditation plays like a breathless greatest hits collection. We talked a few days after its Telluride debut, at September's Toronto International Film Festival, two days after the attacks in Benghazi, and only a few weeks before the 2012 presidential election. The Act Of Killing opened in late summer of that year.

After your film, I blame Elvis Presley for everything.

Oppenheimer laughs.

Well, I am tempted to clear just one thing up. Which is that I don’t believe, in any way, that violent movies create violence. I think they inflect how we imagine ourselves, and how we take pleasure in violence. And that is a difficult and provocative thing to say, that we take pleasure in violence, but we are the only species that gathers together on the playground to watch each other beat each other up and scream "fight, fight, fight, fight." No other species enjoys watching violence. Other species, they either join in because of some sort of maybe instinctive reason to join in. Or they run away. But we enjoy it, if not all of us. I’ve never enjoyed it, but I only once was in a fistfight. I was in the second grade, I was being bullied, I hit the guy, and I took real pleasure in the moment of hitting him. And I sort of fired up to hit again, and I think I lost. And that was it for me. But there is a rush and a thrill to power and to violence. A guy said to me yesterday, a CBC interview, and he said, "I think those men must have never felt as powerful and as alive as they did in the moment that they were killing."

I think that is more complex, your film demonstrates that is banal and reductionist—

But I think it’s interesting, I think in some ironic way, when they're reenacting what they do, they perhaps think that they are making it okay, what they did, by somehow… As Anwar says several times in the process, "I want to make a beautiful family movie about what we did.” Well, the idea that he's making it okay, by representing—he's trying and he fails—but to represent, as something as beautiful and okay.

At the same time, I think he is compelled to tell the story in the same way as victims of trauma, although I am not saying that they're victims. But they’ve been through a trauma that is undeniable. They're compelled to tell the story, to repeat it, to make it okay, the way we produce scar tissue around a wound. But I think something happens that's unexpected in that journey for them, which is that they find that they are reliving. Not just acting, and the reason they are reliving it, this goes back to your point, saying we can blame Elvis for everything. At the time of the killing, Anwar came out of the cinema, feeling like a gangster after a gangster movie, feeling like Elvis after an Elvis movie, and then acting was always part of the act of killing for Anwar, acting was always part the process, it was a resource of the act of killing.

It was always an "act."

It was. It was always an act. So when he reenacts it for me, hoping perhaps to make it okay, to make it beautiful for the public, to make it okay for himself, something banal enough that he can speak about without trembling. But nevertheless not giving up the goal of making it frightful to the survivors who live around him, who he seeks to intimidate and keep docile, through what he hopes might be a show of force. He actually finds that he is reexperiencing, or experiencing again. a mode of performance, a kind of acting. A behavior, a way of being, a form of subjectivity. It's very similar to what he was in, in 1965, when he was killing people. I don’t say the same, because he is not killing and that's my crucial point at the end of the film. But similar. Similar enough that he slips into a kind of trap. That I didn’t lay for him, I didn’t anticipate it. I had him dramatize what he did, because they wanted to. And because I understood that was the best possible way to understand the big story in front of the camera, which was not what happened in 1965. Although that’s important, that would be an interesting historical documentary or book. And there have been things made about.

But what is the nature of their impunity today? Who are they boasting for? What is the purpose of that boasting? How does it perform in the world? We see it most vividly in the talk show where they produce a kind of chat show that could be right out of a kind of parallel reality where the Nazis win and forty years on, they make a chat show where they invite aging SS stars on a show. And they boast about killing people. And they say it’s beautiful and wonderful and God hates the Jews… and that’s why the film they're making is so beautiful. That's a kind of show of force.

I was trying to understand, how does this society imagine what they've done? How do these men imagine what they have done? If I bring them together to reenact together—I bring in ministers from the government, leaders of the paramilitary group, other, younger paramilitary members. Their families, their friends, members of the public, at least in the street audition, although we never use those people in that actual scene, because we wanted to be sure that in the massacre on the village, those were all people personally connected to this paramilitary group. How do they collectively tell the story? How do they navigate the story among themselves? But in that process, this unexpected thing happened, where I think Anwar trying to deal with his trauma, by reenacting it, and making it "beautiful," as he says. And by at least recognizing it, hoping that through the volume of repetition, he’s recognizing the trauma again and again and again.

Every time he does a reenactment, plans a reenactment, says, "Our film is going to attract such a great audience, because there has never been a film where real killers are killing people." Apart from snuff films, which I am not sure even really existed. But I guess there are of course videotaped terrorist killings—

Daniel Pearl would be one, but that’s a political act, not a recreation, not a fiction, a whole other situation.

So Anwar's right, there has never been another film like this. He thinks that'll make it beautiful, and attract an audience. And it has great scenery and a love interest, and it’s fantastic. He's trying, through the force of insistence, insisting again and again and again that this will be okay, to bury his trauma even as he is reliving the mode of performance that he was in at the time, the disassociation from reality that he was in at the time. And I don’t like this word, disassociation, from reality because actually, it is reality. We are constantly disassociating. I am disassociating from something in myself, by talking to you in this focused way. I am not focusing on my stomach, or my hunger or the fact that maybe I have to shit, who knows? I am talking to you. He was killing… I think he slips into a trap in a way. Which none of us understood? It was very painful for him and very painful for me, and very painful for the audience.

How old was Anwar while shooting?

Let's see… if he was 25 in '65, he was 65 in 2005. So, 65 to 70.

He looks like a middle-aged Mandela, which was weird at times.

When we filmed the waterfall scene, that was actually, that's a tourist attraction. And there are men who look like Anwar from Indonesia, because Indonesia is geologically part of Australia. People from eastern Indonesia can look like Anwar, with curly hair and darker skin. But it’s unusual in western Indonesia where we made the film, so we were filming this waterfall scene and some tourists came and saw Anwar, and they were Dutch tourists and they said, “Is that Nelson Mandela?” And when they watched the massacre scene, and it’s not in the film, but when they watched the rushes of the massacre scene as a group, all the people who were in the massacre were watching together and the guy who says that “the younger generation must always remember what happened” on the talk show, raises his hand and says "You look just like Nelson Mandela!” right as they are watching him massacre a village.

And of course there is a line in the film where he says that they say he looks like Idi Amin. There's a director's cut of this film, a longer cut, which is not cinema length, it's maybe for special festivals, and it'll be on DVD, which has many special things about it, like the final scene on the roof is all one shot. There are no cuts. But there is a moment [in the longer version] on the talkshow where the first question they ask is, “Who is your favorite movie star?” and Anwar says, "Sidney Poiter, because I look just like him.”

Yes, it's about impunity, yes, it's about how our societies are built on killing, yes, it's about the joy of killing and if that didn't evoke "The Joy Of Sex," that would be a great title.

That reminds me of something of Errol Morris said to me. In third grade, he had a teacher who sent him to some psychologist or whatever they had at the school at the time, who asked, “Errol. Have you ever had any unwanted thoughts?” and 8-year-old Errol said, “Is there any other kind?”

Oppenheimer laughs.

That sounds like Errol! That's where Errol and I are probably the most different, by the way. We had a great time in Telluride, arguing with each other. We'd do these panels, and as you know, he loves the movie, he's been just the best, both he and Werner have together have been just incredible for the film. And for me, to have them see themselves? I mean, they're my past as a filmmaker, and for them to recognize themselves in my work and step in and say wow, this is taking it to a new place and we want to be involved with this, is just amazing. But in Telluride, Errol and I, our dynamic, we didn't know it would be this way, was just like banter the whole time. I guess the difference is, for me, all thoughts are wanted! And for Errol? All thoughts are unwanted. Which means that Errol's, I guess, state of nature, is—

It's his relentless forensic brain. And the way he looks at a thing—

Can you imagine how exhausting it would be to be Errol Morris?

From the very first exposure to even the idea of the man, of Errol, from when he got started years ago, this mind that doesn’t stop: I think of the story of what happens when you give a sugar cube to a raccoon, it's always going to go and wash it, turn it over in its paws under the water—

"Where'd it go?"

And there's the quizzical look. And if you're cruel, you give the raccoon another one.

That's how exhausting it is, until it disappears and evaporates in his own hand.

Anwar intuitively deals with these postmodern ideas about representation. But then you have the childrens' reaction, "Look, it's granddad!" He's got these two kids in front of him and he briefly thinks it's too violent, then "Oh they'll get it." And they understand that grandpa is acting. He comprehends the idea of what is romanticized on screen but what happens in terms of allegory and representation of violence, he still doesn't get the full implication—

That's absolutely right. It goes back to my whole idea about filmmaking, which is that the moment we film with anybody, we are creating. We are not documenting, we are creating. Whatever, if I'm going to film you go to work, it's an observational documentary, we talk about it: I am going to film you going to work today. So when you are going to work you're thinking about me filming you, and at best, you become so used to me that I can still capture authenticity, despite the fact that I'm filming you. So I was filming. I have this feeling that when you film with someone, you are creating reality. Always. And of course when you are filming some of the other things that are happening, is that they are staging themselves for you. As Colin McCabe said once, Hollywood is the world's etiquette manual. Never more so.

People watched, they learned how to smoke, they learned how to kiss.

Absolutely, and Anwar learned how to strike his match in that scene when he says, "I'm a gangster." He's in between takes, but it's from watching gangster movies. And nevermore so is it the world's etiquette manual than when you are being filmed, even if it is just an interview. Even if it's just the simplest scene in documentaries. This whole idea that in documentary, we document, it's an illusion. We create a reality that maybe we document through the process of creating it. Through the process of documenting it, we create it. But we are never just documenting unless it's a sports event or a political rally. And even if it is an ambassador being dragged through the street, they are doing it in anticipation of your camera documenting it.

I've only seen a still from [the only days-before events in] Benghazi, but it looked like the images from when Saddam Hussein was pulled from the so-called "spider hole." Just as with Gaddafi. It's some brief eight-second thing that somebody shot cell phone footage of. The seven-, eight-second clip of the vanquished—

It's a genre. The seven second clip where the father is toppled. Yes. But, I think we create reality when we film people. And they are staging themselves and imagining that they're being filmed.

"How do I look?"

"How do you want me to be seen?"

"How do I look to you?"

"How do I want to look to you?"

"How do I look to the world?”

"Who is going to see this?"

That's exactly the questions that came to my mind when I first met these boastful perpetrators who seemed on the surface, remorseless. Who are they boasting for? How do they want to be seen when they boast? How do they think I see them? How do they think their society sees them? So then I realized the moment, if I'm filming them, if I give them the opportunity to be filmed however they wished to be filmed, to do whatever they wish for my film. Then it's like, they place their imagination through a prism—

—tapping into subconscious implications you wouldn't have with common blah-blah counter-shot talking heads.

Yeah, but I am also able to get all the secondhand, third-rate stories, and images, and recycled pieces of cinema, and television that go into their self-conception. Of course then, the story of these reenactments is sort of disappointingly simple. I come, I'm an American moviemaker, they love American movies, they love America because America supported them. They've never seen a documentary except for the news. They see me come with my camera, they just assume I want to make an American movie. Well, okay. Then they want me not just to show tell what they did, they want me to show it, they want it look like it was, and maybe it should have blood, and it should be scary. All I had to do was bring my sensibilities and my questions as a filmmaker to their expectations of me and be non-judgmental. I could be perfectly open, I had to be, because as you see in the talk show, [the words used right away] like extermination and killing—

And that sweet young host, she can't stop smiling…

Yeah, or have a heroic connotation as they might have had in the aftermath of the Holocaust if the Nazis had never lost. Whereas for us, they have a genocidal connotation. I could simply withhold my judgment and listen as a human being to another human being. And indeed of course, I was encountering human beings. I was encountering not monsters, I was encountering human beings. Everybody is a human being, every human's a human being, it's a tautology, there is nothing more to say about it. That's it. I mean, "psychopath," "monster," that's reassurance. They are human.

The projection onto "the other"—

Yes, and it's about fear. It's one thing that underpins the fear, which we don't like to look at. It's not only about fear, going back to the kids on the playground, it's also about joy. You know Obama is the first democratic President reelected after Truman who's not vulnerable on national security. Why? Because his policies are popular. What are the policies? Drone strikes, indefinite detention, impunity for people who we know have committed torture. It's popular. Jack Bauer [and "24"]… Even though we know that the torturers in Guantánamo got their methods of torture from watching Jack Bauer, just as Anwar got his methods of killing from watching James Cagney.

They must know, they might believe that Jack Bauer is an appropriate, heroic model for what they are doing. Because of the ticking bomb scenario that is in play in every Jack Bauer episode. But they know that these people who are in Guantánamo had no contact with terrorist cells from which they allegedly were plucked. They know that there's no ticking time bomb scenario. That doesn't mean they don't believe it when they do it. And that is another great insight I think this film—well, I don't mean great—but the big insight is what we know and what we believe, are, y'know, hardly on speaking terms. They are just totally separate. So, going back to this thing you ask about the postmodern: Once you put a character's imagination through a prism, once you create the conditions, as I tried to, for an observational documentary of the imagination, as opposed to an observational documentary of kind of simulated reality, where there is no camera present, then, you are able to see, as I said, all these secondhand, third-rate generic images that go into one's self-conception and self-staging.

He doesn't lose because he's corrupt, he loses because he doesn't have enough money to give people bribes. And that may be why the Democrats lose. Because corporations are bribing Republican candidates more than they're bribing Democratic candidates? And make no mistake, they are bribes. I mean, they are paying for advertising, and they expect favors for it. It's a great deal for them, they put a few million dollars into candidates' elections, and they get billions of dollars worth of deregulation.

At the end of the viewing scene with those grandkids, we had this choice, in the editing. Anwar is watching himself watching. I sort of confront him and tell him, Anwar, no, you are not feeling what your victims felt. That was difficult, but it was true. So I said it. Anwar is watching himself dazed, devastated after he plays the victim. We had this choice. Should he be sitting there in his living room watching that on a TV? Which would kind of evoke the method again? Y'know, the filmmaking method? Or should we cut back to the shot from the film noir? It was a choice, if he watches the TV, he is seeing the small sadness of a television, which we get early in the scene where he is watching the waterfall and says, I can't believe, I am so proud how the waterfall expresses such deep feelings. There, it was helping that story. Helping that narrative to place the waterfall on a television. And make it look like a piece of kitsch in a kitsch sort of living room designed by an impoverished, but all-too-human imagination.

At the end of the scene, you could evoke the method again, by showing the TV. But here it felt like, no, I felt that somehow it was like taking out one color, you've extracted one piece of Anwar's subjectivity of Anwar through that noir tableaux, or he's just sitting there kind of devastated while Herman is comforting him. And the other gangster, Safit, is sitting in the back, looking like he doesn't know what to do. I felt that shouldn't be on a TV. Because that is like a shot-reverse shot of Anwar with another part of himself and it's a devastating, very human part of himself, seen through and staged through a kind of stylized mise en scène borrowed from Hollywood. So it's accidental postmodernity.

And while Anwar has no depth of understanding, intuitively he was behaving in a way that juggled all of that.

He's always acting…. As I said earlier, he was acting when he was killing.

He likes his costumes.

He loves his costumes, and at the end of the film, people ask, "Do you think he's sincere when he's choking?" I think he's really wretching. But does that mean he's not acting? No. That doesn't mean he's not acting. Of course, by then, I had been filming with him for five years, he knows how to use the space, he knows how to use the camera. As I said, in the longer version of the film there was no cut there. It's all like he's perfect. But he's still really choking, and it's still an empty thing, because nothing comes up. He's too empty for anything to come up, as someone wrote this week, and I think it was very insightful.

It's like finally there is this slug in the sound, the sound implies that it's just guhhhh, a slug that's his soul trying to get out—

It's like the demons trying to get out of him, and they can't get out. They are in his flesh, which has somehow already died. I mean, at the end of the film, Anwar is not haunted, he's dead. Somehow one of the ways in which people feel devastated is how they feel implicated. If I told you our clothes are affordable because somewhere in the world workers are producing these under terrible conditions and are too scared and intimidated to fight for better conditions, and the reason they are scared and intimidated is because wherever it is in China or Indonesia, or wherever, there are men like Anwar and his friends who are enforcing those conditions on the ground. And we all know it.

From the street level.

There are men like Anwar paid to be thugs for a big company. HSBC bank has been accused of being the worst bank in Indonesia for hiring gangsters like Anwar and his friends to go after people who don't pay their loans. To burn down their houses, to beat them up, HSBC. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation based in London. And we know it, we know that in some ways, we are guests of at a cannibalistic feast, we are not as close to the slaughter as Anwar and his friends. But we're at the table. And I think that's a really unpleasant, dislocated thing, because there is nothing exactly we can do about it at the level of individual action. We could not fly so we don't contribute to global warming as much, but I don't think that buying organic apples as Slavoj Žižek once put it, is going to solve the problem.

Particularly when they're flown from New Zealand.

Yeah, especially when they're from New Zealand! So I think part of the reason while Anwar's condition is precisely a postmodern one is because he was, and is, a product of globalization. From the beginning. I mean, he was consuming American movies, he was part of a massacre on behalf of American-, Dutch- and Belgian-owned plantation companies for an army that was supported by the West. A kind of a master narrative that was justified by a master narrative of the domino theory that was kind of a fantasy, I don't know what kind of fantasy—probably self-derived from 1940s Hollywood films in the heads of people like Robert McNamara or William Colby, who was the East Asia head of the CIA in the 60s. I mean, the whole thing is postmodern.

There's some concern in the U.S. about voting day vigilantes, who would be dispatched to places where the poor, the elderly, and the immigrants are voting, and challenge every single person possible.

So our democracy will look just like Hermann's campaign! And what's more, he doesn't lose because he's corrupt, he loses because he doesn't have enough money to give people bribes. And that may be why the Democrats lose. Because corporations are bribing Republican candidates more than they're bribing Democratic candidates? And make no mistake, they are bribes. I mean, they are paying for advertising, and they expect favors for it. It's a great deal for them, they put a few million dollars into candidates' elections, and they get billions of dollars worth of deregulation. Then everybody else bears the costs of it. So our so-called democracy in the United States, and I really say "so-called" very seriously, it's not a democracy. It doesn't even have a democratic presidential [system, states elect electors], the whole thing is not democratic. The Senate is totally not democratic because small states, like Wyoming, the average person in Wyoming, has ten, a hundred times more representation in the Senate than your average New Yorker. Why? Because they live in Wyoming? I mean, it's just not democratic, it's not a democracy, the United States, and it's increasingly not a democracy.

I hope The Act of Killing will make people see, yes, it's about impunity, yes, it's about how our societies are built on killing, yes, it's about the joy of killing and if that didn't evoke "The Joy Of Sex," that would be a great title. But it's about us all, Rwanda, Bosnia, these places where the killers have actually lost, or some point afterwards, have been told what they did was wrong, including the Holocaust, I suppose that's the exception, not the rule. People see this, and say what is amazing about it is that the killers are in power. But probably that is how it normally is, otherwise people wouldn't kill! Those people wouldn't kill if every time they did it they got thrown out and punished, people wouldn't do it anymore. Which is why I also think The Hague has a role. The problem is, as Adi [Zulkadry] says in that scene in the car, but he doesn't say it to me, He doesn't say it in the film, but he said, "Why doesn't the Hague come after me?" Because they have no interest in coming after me.

There is a scene where The Hague is broached, but not that specific line.

Yeah, that's not it. But it was in that scene that he says that.

You left cameras running and captured a lot of humor, and that's what one of the smaller gifts of the movie, absurd lines like, "Fuck this umbrella!" I mean, within the setup it's like, "What is going on here?" But it's just the ideal, because not only have you got the big guy loving being in drag, it's also this logical thing, like argh get this away from me!

But it also tells us so much about him! That's the thing when you have a thousand hours of footage and you have to go down to twenty-three hours of scenes.

That took a year-and-a-half with two editors. Then we went from twenty-three hours of scenes to this 2:40 full version of the film. Then we went to this version, which is the longest in our contemporary economy, and cinemas can really bear. 116 minutes, but it can unfortunately be 24p. It shot at 25 frames. But it's about as long as you can get away with. You have to be extremely economical, given that there is such a big political picture to tell, we're walking this tightrope between repulsion and empathy, and before you can have empathy, you have to see the people are human and feel them as people. And so you have to choose moments like "fuck this umbrella." Where you feel Hermann, you feel what he's like, you feel what it would be like to sit there in a dress in the heat, and having an unwieldy umbrella to deal with before you are supposed to be attacked in some crazy scene on an oxcart. So of course one is looking when you have that much material and that big a task of reduction, it's like everything becomes a great one-liner in a way, because you have to be extremely—

—distilled to a point of poetic essence—

Yes. Yes. Even in the 158-minute version is also that. Because you come from a thousand hours, and it's a thousand hours of pretty extraordinary stuff. When I started the editing, I thought there would be a two-to-three part version that was six hours long. I didn't think realize we would be able to get it down as much as we did. And it was a great joy to realize that, wow, we can actually tell this, and create an experience that's this length.

Maybe halfway through, you could still take every single thing in this film as fictional. Everything. Except it would be incredibly difficult get the density of such cultural detail. Or it's utterly true. And the brain sort of balances on the beam and then goes "this is true." All these things that extraordinary become commonplace. Herzog does that too, long takes, distance at first, colorful characters. But whatever is going on within 15 minutes, it's just like ,"This is all so strange, I know nothing about this culture" and it's like, I am just here for the ride. Or simply, what is going on? What the fuck?"

I think that is why—Errol said this about the film. In the beginning, he said, you're introduced to this surreal, this entire other world, and that was a very difficult thing in terms of editing, because if this was a film about the Holocaust, everyone— you wouldn't have to have the first half hour of the film. You'd simply have to introduce these characters and you would know what their role was, you would know it from the story. You could just say, "They are SS officers" in Auschwitz and you would know it. The viewer knows the story. And then the method would have to be introduced, what happened, and the genocide, who the characters are, the political regime that has been built upon it, the paramilitary group, the basic situation of the newspaper office, the movie theater, the relationship to the present-day politicians, and the movie theater gangsters and the method. That was a very, very hard thing to get right.

One of the things my editor Niels Pagh Andersen said, which is beautiful point, he said—because I am a perfectionist—he said "Josh, there is no perfect film. There is just the best film that you can make." And so critics might write, "Oh it feels long in the middle," or whatever, but of course, we tried removing things in the middle. Then we realized you don't have an understanding of what the stakes are, what are the consequence of their impunity? Do you take the guy out with his gem collections and his little singing fish, you lose the hollowness, and it implicates us all as we get back to the shopping mall.

So it is very easy to criticize films. As a director, as you can see I took a very difficult but very essential one, there was no other option, not to use music. Except for their own musical numbers, I use no music. That's hard. It's easier for me to watch other people's films and be like "oh I hate the music," or "the score is unfortunate…" but you don't know what problems are there when you take the music away. Every film that is good is a minor miracle, so, it's very important, especially in documentary—I hate this word, "documentary"—nonfiction, where you don't have a script, almost never is there a perfect film. Where it doesn't sag. But those sections, if you have done your job, are doing work that's essential for the payoff later.

It's a weird thing when reviewers want to be postproduction supervisors when they describe a film. Does “too long” mean it's bad? Did the person fall asleep? It just seems like to be a de facto talking point as apposed to really applying to the thing you are watching.

That's right, and also, there wouldn't be a two-hour-and-forty minute version of this if it didn't do something different. You know? If it just did the same thing but took longer about it, it wouldn't be there. We would have just said, "this is a rough cut, making our way towards our fine cut." It does something else. You can do more things in two hours and forty minutes. The 90-minute version, we made because we were forced to, because broadcasters wanted a 90-minute version. It does less than this version that you've seen. You use the screen time you have and hopefully, you use it well. And in the longer version, because there is so much backstory that needs to be there, there is so much action, there are various reenactments, you have to get through to get to Anwar's conclusion. In the long version there is not much more violence but there is more space to get under the characters' skin. That changes the whole nature of the experience.

At the end credits, I started giggling uncontrollably as more and more names scrolled up that were "anonymous"… It's one last little frisson, another little chill to the whole enterprise.

Yeah, it is interesting you giggled, because when I first saw them when we put those on within the last week, when I first saw that I cried. I was like "Oh my god, all of these people helped me for all these years, they should come to Toronto with me." One is a co-director. He should be here with me. He's not here because it is dangerous for him. He left doing very valuable work in forestry, preventing illegal logging, because he felt that he needed to understand why nothing was changing in Indonesia. I still am worried about him, we're talking every day. "Okay, what is happening? What is the reaction in Indonesia?" The progressive part of Indonesia is saying this is the most important thing ever to be made about Indonesia. It's a rival, it's about the most important part in our history, but it's a rival, is it an almost unparalleled moment in our country's history? This is a big thing for them, and that hey can't stand up and put that your name on it, because of men like the head of the paramilitary group, Yapto [Soerjosoemarno], would have them beaten up or killed if they did. That makes me sad, I can understand as an outsider how you can …

Oh no, the giggling is empathy, it's "Oh my god…" The obscured names just keep rolling. It wasn't the final nail in the coffin it was more like the final stroke, the final gesture, so sad and true.

It is true. That is true.