Loved-In Spaces: James Mangold's New York In Kate & Leopold

An extended conversation about space in New York City with James Mangold, 2001

From the time of Heavy (1995), his first feature, I’ve had interesting conversations with James Mangold about his movies. This one’s about space and time and Kate & Leopold. The now-sixty-one-year-old filmmaker’s thirteenth feature, Like A Complete Unknown—“what a title!” tweeted Bob Dylan—opens December 18 on thirty IMAX screens and wide on December 25. This is a slightly edited version of a 2001 interview.

There’s a welter of plot and characters in James Mangold's Kate & Leopold, a contemporary Manhattan lifestyle satire-duck-out-of-water time-travel comedy from the director of Heavy and Girl, Interrupted.

And that's part of the charm of its romance. Meg Ryan plays a fortyish career woman, a test marketer whose life seems less and less than meaningful. She’s broken up with Stuart (Liev Schreiber), her upstairs neighbor, after four years, and as Kate describes him to her assistant, “Baby, you are one percent of one percent, I went with a visionary for four years, and I had to pay the rent.”

Stuart’s crackpot scheme is to travel back in time and discover the ways of an older island, and without undue fuss, he does, witnessing the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge 150 years ago, but gaining the attention of a disaffected English duke who’s due for marriage (Hugh Jackman, dashing, yes, but also genuinely funny), who winds up traveling back to the twenty-first century with him. Conflict with work? Ideals? How about the perfect man to make the word “lifestyle” leave your vocabulary?

Ryan’s perplexity and intensity charm, as well as her delicious petulance. She’s no longer the kewpie. Mangold and his collaborators have knit a modest yet knowing portrait of the contemporary career woman at work and at home. (We’ll overlook a few moments of bumptious slapstick.) Stuart Dryburgh’s cinematography has a pleasing edge, an almost hand-tinted look. This New York looks loved-in. The script’s brisk plotting and delineation of a close-knit community suggest the English 1950s Ealing comedies that Mangold knows so well, having studied under filmmaker Alexander Mackendrick, who was one of the key practitioners of that dry but lasting work. Stuart calls the plot’s conundrums “a beautiful 4-D pretzel of kismetic inevitability”; Iet's leave it at that.

New York is filled with dreams and delusions, and Mangold does a good job of maneuvering his characters through their intimate spaces. Kate & Leopold is in part an attempt to stand apart from the reigning Hollywood comedy styles of the turn of the century. Mangold discusses some of his inspirations in the conversation from early December, 2001 that follows.

You've gotten Scorsese's Gangs of New York release date since that film wasn't done in time. When were you scheduled for release originally?

We were a Valentine's day release, originally.

It's a small picture, but I was happy to discover how sweet and smart it was.

That's what we wanted. That makes me happy to hear.

It feels like it's someone's New York, a living, breathing place that just happens to have these comic follies in the foreground. The small pointed, satirical elements don't feel like warmed-over Nora Ephron or Woody Allen, it feels like someone else's lived-in New York.

We were really focused on that. We wanted a feeling of New York but we also wanted a feeling of fantasy. I was just trying to connect with the tone of these great romances of the fifties. Fantastically comedic ones and straight-ahead ones. My favorites, I love Breakfast at Tiffany's. I love Billy Wilder's The Apartment. These are movies that I adore. And I feel they have a real character of New York but they also have a storybook character.

The great thing about those movies is that everyone has inventive memories of them. They're not necessarily what you or I would see seeing them for the first time now.

Yeah, but you should see Breakfast at Tiffany's again. It's great. Except for Mickey Rooney as the Asian guy.

When people talk about it, they're talking about their Breakfast at Tiffany's. It's like how two people would talk about their New York—we're each talking about something different, but still the same reigning romantic ideal.

Right. But it's also the sense, I think unlike a lot of romantic comedies made today, there's a sense of real drama in these movies as well as comedy. The characters have someplace to go. They're not written from a kind of market-tested point of likability from the get-go. I think one of the things Meg was really interested in in this role and I was really interested, was that the sex roles are reversed and for once, she's playing the less adorable of the two leads. She was playing an edgier careerist who had lost her sense of romance and how to breathe and how to live and love and was just in this race. Which is more often the male roles in these movies. And Hugh Jackman was the figure of glamour in this picture.

Something terrific about her performance is this sense of earnestness rather than confusion or anger. It isn't explicit in the film, but her performance says, "Where's the pretty picture I thought I was working toward?"

Right. Or, "What is this? There's no there there. What happened?"

I love Bruce Springsteen, and the less produced, the better.

Sometimes I don't want Bob Dylan with an orchestra backing him.

The word "polished" has just come to mean "more" in Hollywood.

The Brooklyn Bridge, seeing that edifice under construction in Leopold's time is a lovely way to begin the film. It’s a monument that still stands, on its own, inside everyone’s history but also existing outside of it.

Well, I’m very interested in pointing out not only the things that are different from then and now, but the things that have stayed the same. One of the magic qualities of [the conceit of] time travel to me is that if you go back to the same island 150 years earlier, what are the landmarks that stay the same as well as the things that have changed? The things that make is seem like you're still in the same place although so much has evolved. New York is a town that really makes you think about history.

Oddly enough, Kate & Leopold fits into a familiar Miramax genre--romantic comedies where time and fate may keep lovers apart, rather than societal restraints. This year alone, there's been Amelie and Serendipity.

This movie was in development with Miramax seven years ago. I came on about three years ago and soon as I finished Girl, I did a draft of this. The genre of fate and destiny movies never... Maybe Harvey could talk about that.

For you, what have been the essential changes from the time of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge to today?

Well, It thought, one of the biggest things, and it's why there's the [movie preview] test screening stuff in the movie... [a scene which has mostly been cut from the release version] I wrote Meg as a market tester in general because one of the things that's really changed... I'm not a historian, but speaking from kind of a sense of zeitgeist, or of an fairytale sense of what past and present mean to us, I believe that back in the day, in Leopold's day, people meant what they said and said what they meant. They stood for things. They didn't put their finger to the wind to figure out what they feel. I think one of the greatest cultural changes now is that we're such an incredibly connected society, interconnected with people, that the President gives a speech, and you turn to a friend and say, "What did you think?" And your friend will say, "Well, I think it went over well." It's like, "What about the content?" Not about how it went over.

It's amazing the amount of time that regular, rank-and-file Americans spend talking about the box office of movies or what record is number one or whether Michael Jackson's new record is doing as well as his last one, when in fact they haven't even listened to it. Our dialogue becomes almost content-less. People like to talk about what's selling as opposed to what's inside of things. And in a big way, I think that's the numbness I was trying to create for Meg's character, this sense that she is part of this culture of marketeering. Of selling but not ever even being in touch with what you're selling.

A line that fits into that is when Leopold says, "You speak less French than possibly even I do." Leopold is speaking out of turn about himself, blunt about himself, which is a double-edge about speaking directly.

Someone like J.J. [Kate's quietly supercilious boss at the research firm] is completely baffling for Leopold—or not—he may remind him of his Uncle Miller [who insists back in the nineteenth century that he is old enough to find a rich woman to marry and settle down]. The fact is that the kind of indirectness [is unknown to Leopold]. One thing that was very clear about Leopold is that he says what he means and means what he says. And that's a very attractive thing. In a man or a woman. That it's hard to do what you think it today's world and not be thought of as an idiot.

There's the old Mark Twain line, "it's better to be thought an idiot than to open your mouth and remove all doubt."

Right. And I think it's something more and more we've gotten away from.

Oh, we were very conscious of the dressing of her place. And Liev's. We pulled everything, my god, Kathy and I, Kathy Konrad, the producer—my wife also—and I walked those apartments. We took them apart and put them back together. We had so much shooting to do there. We were really concerned that you felt an inner romantic in Meg, that the place was pretty, but lived-in.

Knowing your background, including studying with Alexander Mackendrick, twenty minutes into the movie, I was thinking, oh, Ealing comedy.

Oh, I love those films. Ladykillers, Man in the White Suit.

I was rereading your appreciation of Mackendrick in your afterword to the script of The Sweet Smell of Success and thought, too, of his portrait of 1950s New York in that picture. In Kate & Leopold, there's a sense of how the neighbors in your picture interact, in the hallways, on the fire escape, watching the neighbors and the street below. Just like in Ealing. Was this kind of thing in the draft when you came to it?

What it was about, I mean it was very different. The thing that's constant is that it's about a Duke from the past coming forward. In [Steven Rogers'] draft, Meg was a time travel scientist. So, Liev's character didn't exist, Breckin [Meyer's] Bradley [Kate's goofy younger brother] didn't exist. The whole world of her corporate... She was the scientist. When I think of Ealing comedies, I think of a closer-knit sense of community. The scope of the movie is about a very specific bunch of characters. I don't know how to explain it. There's a folksiness or an earnestness to those films. I think it's something we've gotten away from in the calculated nature of how Hollywood movies, specifically romantic comedies, are made. Y'know, slap two stars in, throw on the pop songs for the montages and go. I think you're dead right. I mean, what ties all these things together, whether I'm referencing Wilder or you're bringing up Ealing, those films, it's a day and age when comedies had more of an earnestness about them. There was more of a sense of meaning coming from the comedy. It wasn't just, y'know, expanded SNL sketches over two hours. That there was some kind of belief that the form... Sometimes going for a laugh isn't the smartest thing. Sometimes going for a different feeling is better. We've almost now turned comedies into something where they have to keep us rolling in the aisles for two hours but you kind of can feel empty after two hours. What else did I experience besides laughing at all this toilet humor? And the bottom line is that I think there are some great films that were made twenty or thirty years ago or more, but you laugh but you also feel and think. Again, the Ealing Comedies, Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Capra, I mean, there's a ton of them. There was a time when it was one of the things that we, the Hollywood machine, the American film industry knew how to make better than anything.

You have a lot of moments where characters let things sink in, a sweet version of a "burn." It's nice that every character has a moment here they're allowed to be pleased. It gives a different tempo to it all, taking these in-between moments without hurtling to the next plot point.

It's letting things breathe. Absolutely. As much as this film is being sold on the chivalry angle, and I think it's real, that's what makes Leopold so appealing, the movie itself has a kind of kindness to it. It has a kind of graciousness to it that to some may seem a little antiquated, and to others, I hope, may seem very welcome. It's a courteous film. I think it's not reserved or stiff, but there's a kind of earnestness.

You present Meg as the NRG-type research hack who could easily become the soulless Faye Dunaway in Network, but within the next scene, in the taxi, she becomes a real—

I think that's true. She's clearly at war with herself, a romantic who's buying into... Look, these are questions I have to wrestle with. A lot of this crap, testing and science and... A lot of it's very smart. None of it's untrue. It's just, is it robbing it of something, like our own instinct? In the sense of what she has to do at the end of the film, would any of this knowledge she's developing help her make the most critical choice she had to, about how to spend her life or who to spend it with. The truth is, there's no amount of testing or knowledge or forethought that helps you make decisions like that. Some primeval decisions in life have to be made on gut.

Speaking of such a thing, was there ever a point here you ever dealt with on screen the fact that Liev's character had slept with his forebear? He's been making jokes in interviews. [This was removed from the release version.]

Right. No, we dealt with it only to the degree of laughing about it. I just thought it was kind of fun.

It's a very odd thing. In Back to the Future, that's a major, Oedipal plot point [which no longer appears].

Well, because they're over five generations apart, it certainly didn't qualify as anything resembling incest. And also since it's technically impossible to sleep with your great-great-great-great grandmother. it's an impossible incest, but who knows? Certainly, once Meg's gone back to the past, her relationship with Liev lies in the future, so nothing she does in the past affects what she does in the future.

It's nice, too, that certain things don't become cumbersome, that issue, and also when Leopold has to return to the past, it occurs off screen, we don't have to see yet another CGI leap through time.

Who needs any more spiraling CG effects and star gates and swirling voids of time? We felt like dealing with it like an old movie. Just do it and get out. What was also interesting to me about Liev's character, Stuart, and Meg's character and Hugh's character were related, it wasn't like Hugh was just Superman. It was like Liev, the fact that he comes from the same stock, it says how men today are a product of their time, not their breeding. It isn't just, “Oh aren't English boys nice?” Even an English boy today is a different kind of creature, those times produced a certain kind of man and woman. You or me raised in those times would be very different people.

We don't how intense Stuart and Kate's relationship was, but it's also nice that he's not just the bad, failed old boyfriend. Despite her saying, "Baby, you are one-percent of one-ercent, and I went with a visionary for four years, but I had to pay the rent," he still helps her to improve her lot and improves himself in the process. He's gracious toward his ex-slash-friend.

I think his character really grows during the movie. I don't think he's so generous in the beginning, but I think by the end of the picture, he's... I mean, Hugh is like Mary Poppins in a way, everyone in his wake grows. even kind of, you look at J.J., the boss, by the end of the picture, he seems more clear and sure-footed and less smarmy. The whole... That idea, that somehow everyone in the wake of Leopold's movement, cutting through this water, kind of just becomes more evolved, gets better, finds themselves a little more, we were really conscious of. And I know Liev was concerned with giving himself... He didn't just want to be the manic bad scientist, he wanted to have some place to go.

And also the ex-boyfriend, dare we say, "dick," character we see all the time.

Right. And find an interesting way to turn that up. Not only is he the ex-boyfriend, but he facilitates them getting together.

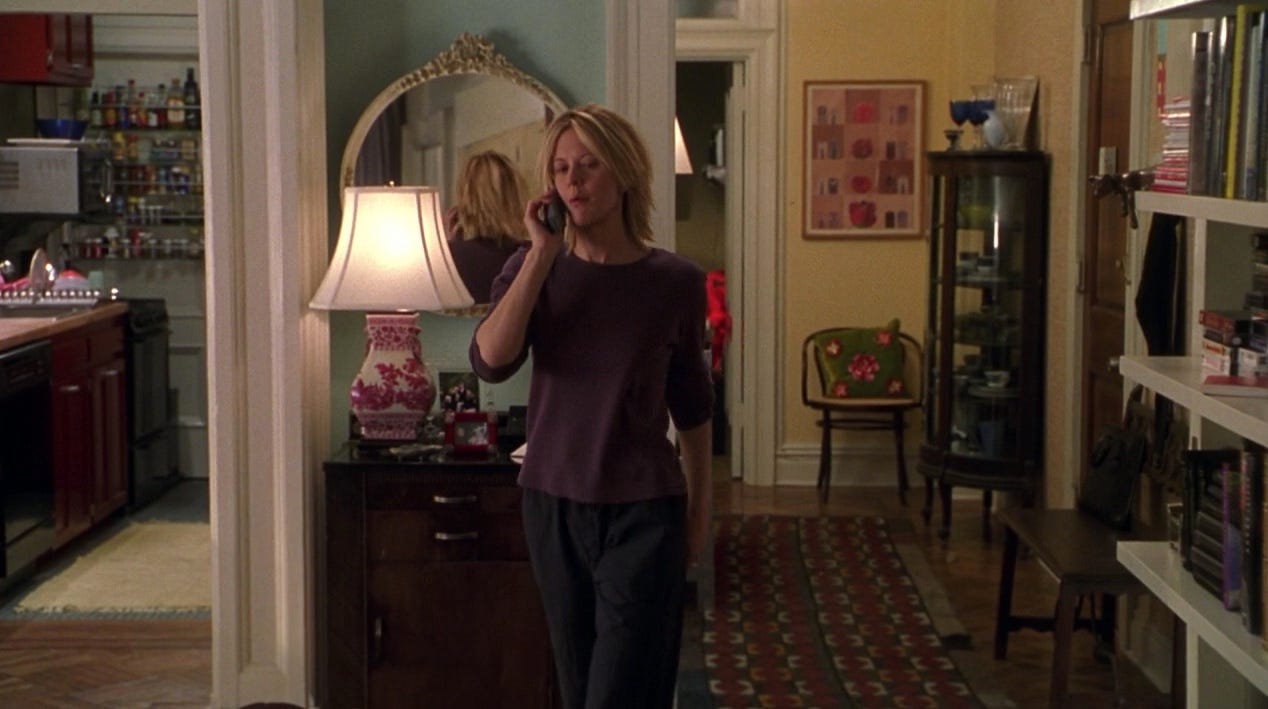

The atmosphere is charming, everyone lives and works in desirable spaces, but it isn't suffocating like some pictures, say, The Royal Tenenbaums [2001]. It's not distracting, but it looks like a smart, lived-in world.

Oh, we were very conscious of the dressing of her place. And Liev's. We pulled everything, my god, Kathy and I, Kathy Konrad, the producer—my wife also—and I walked those apartments. We took them apart and put them back together. We had so much shooting to do there. We were really concerned that you felt an inner romantic in Meg, that the place was pretty, but lived-in. Mark Friedberg, the production designer, he did an very interesting thing. Which he was very, he has this theory that one of the things you go wrong with when you build sets is you tend to build, you tend to decide what period the building was built, a room that looks like a, y'know, a room in a structure built in 1920 or whatever. He said that the real truth is that most buildings were built in 1920, then renovated in the fifties, and then someone did work in the seventies. So he always tries to think about the sets that way. I mean, not that you'd give it this much attention, but I think it gives it a real feeling of realism. Mark designed it like it was a prewar building that had been retrofitted with plumbing and then cut up into other rooms. There was a way his logic allowed him to cut this place up in a way that feels real.

There’s stuff the way it would be in a confined New York apartment, and they're not outsized like an apartment on television, one of the sets on "Friends."

I've lived in New York City and know what's possible for people to afford and it gets downright silly. Also, I like, because things are opened up by playing scenes from above [in Stuart's apartment] and below [in Kate's apartment] and the fire escape, I always felt like we had one very big apartment with all these different rooms as opposed to two separate rooms. I felt like there were all these choices where action could play.

Here's an authentic New York detail: You see Meg barefoot a couple of times and the soles of her feet are dirty. Most women I know in New York are unselfconscious that way... padding around, taking up the grime.

I mean, I don't know about... I don't know what that is, but that is New York.

It's being comfortable with—or resigned to—the everyday sooty character of the place.

None of us, Meg included, had any problem with trying to make things real. Making a fantasy film doesn't mean you have to make everything ludicrously clean or buffed-up or like a Doris Day movie. I think Meg is very conscious of [things] feeling lived in, being conscious of where she puts her coat and where she'd throw down her keys and when she'd kick off her shoes and when she'd be barefoot. I think she just made herself at home in that apartment.

A lot of directors go for gloss, as if the characters were living in a commercial. Obviously, Dryburgh's an outstanding cinematographer, but how'd you arrive at this look? Things are a little grainy, but there's a nice marzipan edge to the colors.

We wanted almost a three-strip Technicolor feeling. We wanted a 1950s look to the movie. I don't know what else to say about it, but that's what we were going for. I loved the way this picture looked, even in dailies I was in love with how the movie was looking.

And it's nice that the effort to use CGI is spent on the Brooklyn Bridge under construction instead of just more whooshy time-travel vortex effects, as you were saying.

I'm very allergic to that commercial feeling. I feel like it's almost anesthetizing, like we've almost learned how to turn off commercials in our brains, and when movies look like them, I feel like we're not engaging them. I can think of a lot of major movies in the last year that are incredibly proficient technically but almost to the point of having no power. They become almost unfeeling. they're like an overproduced record. I know it more from music, I mean, I love Bruce Springsteen, and the less produced [he is] the better. Sometimes I don't want Bob Dylan with an orchestra backing him. The word "polished" has just come to mean "more" in Hollywood. It's like more isn't always more. Sometimes just allowing actors the space and a beautiful shot to perform in is the best "more" you could have.

You've always described the approach to your first feature, Heavy, as an attempt to recapture the gestural weight of silent movies, of allowing eyelines and reactions to carry so much emotional import. Here, you're allowing a lot of instants of revelation, realization or goofy joy instead of hitting the next plot point right away.

We're so used to those plot points, I feel bored with them. It almost seems that the only thing that makes it all interesting anymore is what the actors and the director do with these moments, how we riff on them instead of just dwelling on the, "Bomm-bomm-bom! He's sleeping with her! Bomm-bomm-bom! The weapon's in the drawer! Will the bomb get defused before the clock runs out?" It gets silly. These plot points have been well-known since Shakespeare, and what makes things work is the quality of the writing and the quality of the acting, the quality of the direction. When they work, it's not so much making big choices, as just making living choices, human choices.

When I hear someone say, the stories have all been told, I always want to say something like, yeah, but they haven't been made with Meg Ryan's face at the age of 40.

It hasn't been told. And you know what else, they have all been told before. The act of going to the movies is not always an act of reinventing everything. for me, on this picture, I was trying my hand at something I had seen and loved. I wasn't presupposing I could reinvent the romantic comedy. I was just hoping to make a good one that I would like to watch. I miss seeing movies like this. I miss seeing movies like The Apartment, or Tootsie, for that matter, movies where you had real good actors committing to outrageous circumstances, a kind of sure-footed sense of storytelling. As long as it says something, and something you might not have heard this way before, that's enough for me.

There's an intelligent modesty to that approach, instead of, "By God, I'll change it all!" Instead, you're investing yourself in stuff that you love.

You can't do that with every movie. I mean, you can, not that I've done it with any. I think sometimes as filmmakers we can get too aware of our political power. You can become a hack, where you're just out to make money, which is not what I'm about, or else you can become someone who's out to redefine the medium with every picture. I don't think either one is useful in your head. Some of the greatest filmmakers, whether Orson Welles or Stanley Kubrick or Alfred Hitchcock, were great storytellers first. They didn't sit down every day and figure how they were going to turn everything on its head. They actually just set out to make great movies and the stuff they did, it was who they are and the way their minds worked that their movies unlike what you'd seen before.

Stanley Kubrick was saying, this is what's in my head and I have to get it out.

Right. He was making the movies in him. It's us, it's the audience, that realizes they're challenging our notions. For him, they were his notions.

He couldn't have done it any other way if he had tried.

I don't think he could have. that's the beauty of it. Sometimes we're too aware. Wanting to formally reinvent something for the sake of reinventing it is not good. I think you have to have a good reason. You have to know why you're turning something on its head.

"To thine own publicity be true."

No, I love ambitious directors succeeding or failing in any way. It's a lot more intriguing to me than people who are just putting out more Big Macs. But I do think that we tend to anoint people awfully fast. I think that's the press looking for new filmmaking heroes. The danger is that every year we find the new Fellini, and then in three years, I don't know where they are anymore. Why don't we calm down and let somebody finish more than three movies? Before we anoint them to the level of someone who's made thirty-six films.

The studio directors often had a whole life behind them at 35 or 40 before they began making movies.

That's rare enough nowadays, too.

At festivals, there's a lot of hullabaloo about the new guys, but there are a lot of good third and fourth films, if directors get a chance to make that many.

They're considered a failure at that point, that's what's really wrong. They took too long to get there. It's the age of the phenom. [The press] wants the guy who's Dwight Gooden, Roger Clemens. They want the guy who gets to the mound, throws, strikes, he's a phenom. But that's not how it works. John Ford made a jillion movies. Alfred Hitchcock made 36 movies before he was Alfred Hitchcock. Anyway, I'm happily on the long road. I always figure the turtle might win the race.