Millennial Mambo: Baz Luhrmann Makes Music Because He Can-Can

The director of Elvis talks musicals in 2001

Baz Luhrmann wants to astonish. He says he wants to “reinvent musical cinema,” and, in the Australian director’s first two movies, Strictly Ballroom and William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, he took his first tentative steps, making a frenetic scratch-mix of music and history with all the prankish savvy of contemporary theater and opera directors.

Contemporary American movies are usually slaves to naturalism, but with his third feature, Moulin Rouge!, Luhrmann is a slave only to the rhythm. Making a movie that is choking with extravagance and detail and a love of “love,” Luhrmann is working in a form akin to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia: an impatient, operatic too-muchness. He designs and directs and music-produces not as though he’d never be allowed to make a movie again, but as if no movie would ever be made again.

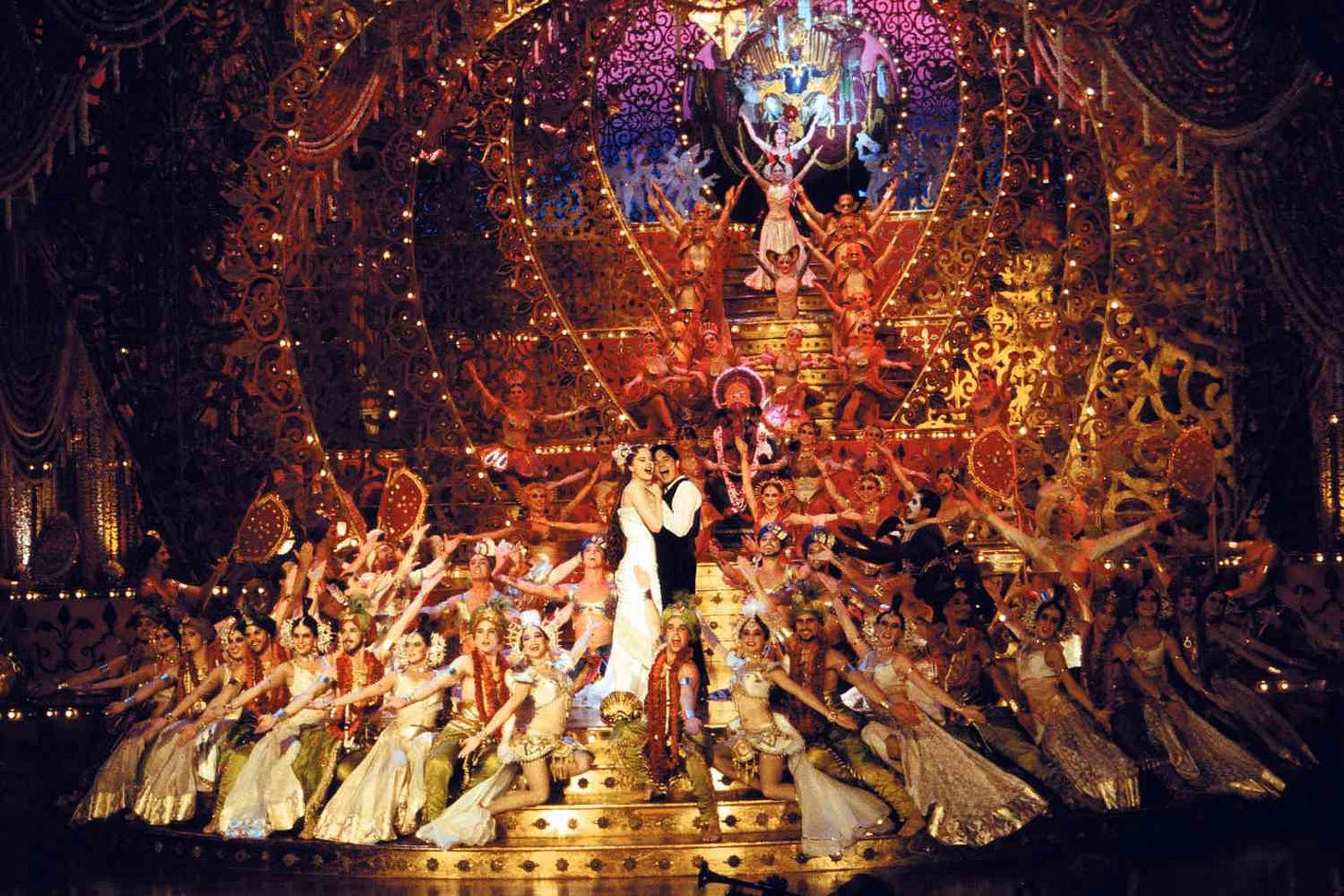

While the story is a mass hallucination of the half-remembered tropes of the turn-of-the-century Parisian bohemian epoch, the music draws from dozens of sources with improvident alacrity. Luhrmann’s show-within-the-show is an India-set stage production that mimics the wild fantasias of multi-hour Bollywood musical epics, and the feast is for the eyes as well as the ears. But the ditty-simple libretto simply sets us in Montmartre, 1899, where “a Bohemian storm is brewing.”

Courtesan Satine (Nicole Kidman, icy, then champagne-giggly) finds her future and that of the Moulin Rouge nightclub have been staked by lascivious impresario Zidler (Jim Broadbent, bellowingly merry) on her accommodation of a dweeby Duke (Richard Roxburgh). Young writer Christian (Ewan McGregor), new to the quartier, falls in with Toulouse-Lautrec (John Leguizamo, playing him as the truth-telling soul of the scene), who leads a bohemian band of artists who are impressed only with “truth, beauty, freedom, and love.” Lautrec pushes Christian and Satine into each other’s arms in a screwball comedy turn of mistaken identity: Satine believes Christian is the Duke. Cue the refrain: “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return.”

An absinthe-drenched reimagining of pop opera and the American musical comedy, each and every scene is a full-throated shouting down of any notion of understatement. Luhrmann is fixed on attaining the authentic through the inauthentic. How do we get to genuine feeling when we’ve been told how to feel so many times in movies and songs?

Contemporary American movies are feats of naturalism, but with Moulin Rouge!, Luhrmann and co. are interested in feats of levitation. They’re willing to tempt the notion: Can you die of too much beauty? If anything will sell the movie to the world at large, it’s the dense, generous, postmodern soundtrack, delineating the recombinant DNA of a century of pop music: the “cancan” heard in Moulin Rouge! is courtesy of Norman Cook (Fatboy Slim) who sings, “Because you can-can-can!” over a track in his family rave-cum-frat-party fashion.

The movie unfurls on lavish sets filled with color and action, augmented with swooping, physically impossible, computer-effects-enhanced shots of the end-of-the-century capital by day and night. The Duke agrees to finance a show, which mirrors the love-intrigues in the “real” world and is designed and told in the excessive, brilliantly colored style of Bollywood musical epics. But you don’t have to know that for the movie’s look and insurgent soundtrack to knock your socks off. Everything is iconic: the characters exist only in our visual rapture (or lack thereof) in watching them maneuver around their feelings through song.

Most effective is how Luhrmann and co. weave their soundtrack from dozens of sources, with the actors singing their own roles. The best example might be a love duet between Satine and Christian, when they are in full swoon over one another, which starts with bits of Phil Collins’ “One More Night,” segues into U2’s “Pride: In the Name of Love,” veers into “Don’t Leave Me This Way,” Paul McCartney’s “Silly Love Songs,” “Up Where We Belong,” and then David Bowie and Brian Eno’s soaring dirge to teenage love, “Heroes.” The ace in the hole? The medley then moves to the climactic soar of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” and Elton John’s “Your Song.” Sounds either dizzying or dumb, but, in fact, it soars above jokiness into some kind of sensation that finds emotional authenticity in the most synthetic parts of our shared pop consciousness.

There is this perception that someone who makes something goes up on a mountain and simply imagines it. The process so often gets mystified like that. But it’s one thing to have an idea and another thing to make it actually happen.

The “we” that Luhrmann compulsively alludes to in conversation is less royal than communal, encompassing several key Bazmark Inq. collaborators, including production and costume designer Catherine Martin (“CM”), to whom he is married, and Craig Pearce, his co-writer. Feline and impatient, Luhrmann is a cat who is self-consciously hep. With a shoulder-length fall of nicotine-to-gray hair, the thirty-eight-year-old impresario loves “a bit of a chat.” Luhrmann is one of the fastest talkers I’ve ever encountered, and is willing to let his thoughts tumble over each other in his clipped, sometimes nasal speech, as this slightly edited transcript demonstrates. These conversations took place at the Raffles L’Ermitage Hotel in Beverly Hills on May 13 and 14, 2001, a few days after the Cannes 2001 opening night debut of Moulin Rouge! Shorter versions of this interview were published in Expresso (Lisboa), June 2001, and at Playboy's now-defunct website.

The refrain from “Heroes” in the big production number is bugging me right now.

[pleased] Is it?

That and the da-DAH-da-DAH of the “Because you can-can-can” refrain.

The fun thing about it is taking a song you’ve lived with for many, many years. The device in that duet is that it’s all pop, and we’re dealing with it in a very classical form. Because it’s emotional storytelling, it does stick, you know what I mean? Like opera. In terms of what I like on my turntable, I would love to have heard Beck do a remix of it or something.

That song’s meant something to me since I was nineteen, and I’m bringing the backstory of the lyrics to the scene, of Bowie in a hotel room watching a pair of teenage lovers on either side of barbed wire between East and West Berlin, at risk of being shot if they make contact.

Yeah.

And you make it so exuberant, soaring, when Satine and Christian light up toward each other in the medley.

It’s inherent. I think what you pick up there proves to me that when a piece of art is true, it transcends time and geography. Let’s take your point on “Heroes.” Whether you knew that story or not, (the link you make with the original clip) is embodied in that: it’s a hero’s song, about a boy and girl saying, “Look, just for one day...” It’s got incredible hope yet sadness in it. Then when, suddenly, it’s transplanted to a scene that has the same notion embodied in it, it amplifies the emotion. Same with, say, the tango piece, right?

There’s a Flaubert quotation I ran across the other day that seems to suit our give-and-take about process: “Talent is long patience, and originality an effort of will and intense observation.”

Boy, has he been around recently in my gig? I don’t know if I’m very talented, but I do know that creativity is exactly as he says. There is this perception that someone who makes something goes up on a mountain and simply imagines it. The process so often gets mystified like that. But it’s one thing to have an idea and another thing to make it actually happen.

I admire at least the simple description of your communal process, a kind of magpie's distillation of all these influences. It’s like a rare, modest idea that a “vision” can work this way, that it doesn’t burst fully formed from one ego.

It can’t. Unless you’re a painter and it is a relationship between you and the canvas, then the moment you step outside that situation and involve one other person, what you get is totally a collaboration. My job is to know where we are heading. How we get there is totally in the hands of many.

I’ve only ever known that process, from working with my brothers as a kid to what I’m doing now. It’s a richer, better experience to work with people. I think that probably what I contribute to the process is that I help others to give forth.

I was talking to CM yesterday about the idea of “raising the temperature of the room,” the idea that the challenges people who respect and know each other can throw each other make the work smarter and richer and better.

Totally. What we do is argue. [laughs] But in a really right way. What I mean by that is that it’s not personal, it’s just dut-dut-a-dutta-dut and it’s fun. We are addicted to it.

From the interviews you did for Romeo + Juliet and from the pre-release interviews for Moulin Rouge!, the most common set of words is “I believe in love.” I was wondering how, for you, Moulin Rouge! is the culmination of your three films about the killing and thrilling aspects of love?

Well, that’s a good one, that’s a good one. [Luhrmann stands, to illustrate the idea while pacing, folding his jacket over a chair.] Strictly Ballroom is like the pure white light that’s triumphantly perfect at the end: y’know, they live happily ever after . . . well, they get together. It has the resonance of, y’know, love triumphs over oppression, right? We all know that. Boy and girl, young, we will not be artistically oppressed, let’s fight side by side, we fall in love, we triumph. But what happens after that? What’s the sequel? One doesn’t deal with that in a kind of David-and-Goliath myth, y’know. We don’t go and see Scott and Fran move on, move out to the suburbs, open a dance school and argue, and he has an affair. Don’t want to deal with that. That’s the purity of that myth.

Romeo + Juliet is about love in conflict with society: it’s tragic, it’s purely the other way. Strictly Ballroom is purely positive, this is purely negative. We completely lose that in Moulin Rouge! It’s more about what happens to the adult world instead of what happens to them. Satine discovers love before she dies. She is “like a virgin, touched for the very first time.”

Touched by love for the very first time.

The first time. Because Satine is born to a world of prostitution. And if you know someone born to the world of prostitution, you don’t ask them, “Why are you a prostitute?” The answer is too simple. It’s like, there’s that, then there’s eating. So she’s never been able to be emotionally involved. She discovers that just before she dies. Christian has this absolute ideal that love will conquer all. But then he discovers that, actually, it won’t, that he can’t control things. His jealousy makes him do a dumb thing and he almost loses her. But right at the very end, y’know, the curtain comes down on them. Whereas love triumphs at the end of Strictly Ballroom, what Satine and Christian both discover is something bigger than love, and that’s death. Something they can’t control.

I’ve made this kind of work all my life. I don’t need to justify it. I spent the first fifteen years of my working creative life doing Brecht and Artaud, materials that were so complex my mother couldn’t understand what they were.

Death steals away Satine. But just before they part, what they discover is the point of the film. For Satine, it’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. And it’s the same for Christian, one hopes, although he has lost this naive, idealistic perception of love, y’know, pure, absolute, unswerving. He’s scared, but he goes on, changed. He doesn’t give up on it altogether.

I basically believe that your relationship to love evolves. I don’t only believe it, I’ve experienced it. I’ve been Mr. Young-I-Will-Never-You-Will-Never-We-Will-Always. We’ve all done that.

Got older and done that. The youthful tack can be delirious, even ridiculous, but you can remember it to find the necessary level now...

That’s right. That’s right. You realize that, actually, there’s another kind of love, y’know. I suppose the bottom line is this: this is an easy answer, or a short one anyway. There’s got to be something good about growing old. You’ve gotta get something in place of all the apparent magnificence of youth that disappears as the years go by, the diamonds of youth and beauty that disappear as you move through life. And that’s a kind of spirituality, a bigger spiritual power.

It’s also the role someone finds themselves playing toward love, as you grow older. A woman I know who’s just turned thirty finally decided to have someone live with her. Now she’s horrified, constantly irritated. I said, “I guess you don’t want to be the old couple sitting around.” Actually, she does, but with the wrong person, it’s turning her manic.

That’s right. You’ve hit the magic number: thirty. This is a generalization, but you turn thirty and that little bit of thing called youth, which you’re not aware of when you’re young, is going. As Orson Welles said [jokey Welles voice], “I know what it’s like to be young, but you don’t know what it’s like to be old.” It’s quite true. You don’t realize when you’re under thirty what a get-out-of-jail-free card you’ve got. Y’know? Then slam, down comes the cage at thirty.

There’s a reason why Hamlet is that age. Romeo has one characteristic: absolutism. Hamlet is the complete opposite: he can’t make up his mind about anything. Macbeth, having gone through that arc, is now engorged with power, and Lear is a silly old man, in a sense. They all have the kind of primary fault of their age.

Speaking of Shakespeare, that brings up a trend among the more interesting filmmakers working today, after they’ve made a few films: the willingness to be simple and direct. Audiences don’t seem to have a problem accepting things being direct once they’re in the seats, but, sadly, with recent work from filmmakers like Wong Kar Wai, von Trier, Wayne Wang, there doesn’t seem to be a critical vocabulary to discuss simple emotionality. That’s going to be a problem with the way Moulin Rouge! gets described as well. Simplicity and directness are sometimes taken for sentimentality or simple-mindedness.

Look, it’s really simple. I’ve made this kind of work all my life. I don’t need to justify it. I spent the first fifteen years of my working creative life doing Brecht and Artaud, materials that were so complex my mother couldn’t understand what they were.

Exactly the same critical response was leveled at Shakespeare and Molière. Because what they were dealing with were audiences from children to the Queen of England. What they had to find was a simplicity in story structure, but a resonance and complexity in the layering. It’s kind of naive not to understand the difference between those things.

“If your story measures the movement toward and

away from love, it’s a song, it’s a musical.”

One’s got to be really, really committed to the journey, the journey of making the art to be received by the audience. It’s not a demographic I’m chasing, it’s a psychographic. Otherwise you withdraw and all you’re doing is hiding in the kind of “let’s hold up signs and symbols that tell a lot of critical folk that they can feel comfortable.” And it’s easy to get drawn into that.

So would a label like “delirious kitsch” be a problem for you?

Well, what are we talking about here? Tastefulness? Because what is kitsch? If we were talking about classical Greek art, statues, and the wall of the Acropolis, we might think of that as being profoundly “tasteful.” But it was painted in disco colors in the time of the Greeks. I mean, all of those statues had rouge and pink faces and brightly colored clothes.

Color was expensive. Only the rich could afford to be gaudy. Only they had perfume and finery.

That’s right. It’s a funny thing about kitsch. If you’re going to make a screwball comedy, for example, why can’t you make it look like an MGM musical? Whenever I’ve ever had someone in the ring about this, they kind of disappear into zero. I remember, in Spain, one guy went into a mumbling thing about “Well, y’know, I just know it’s wrong.” And I said, well, I made a film where there was an all-powerful federation, the president going, “There’s only one way to cha-cha-cha, mate, and you’re breaking the rule book.” When you put rules, so-called invisible rules, next to art, you know someone’s insecure about something.

Sometimes we don’t want to admit we’re swept away by a movie, so this kind of complaint is a way of resisting that engagement.

What you’re pinpointing is important. It’s all about “audience participation cinema”: it demands of you that you participate. It says to an audience, “Hey, whoa-whoa, wake up, wake up, you’ve gotta be involved or forget it, get out, y’know. If you’re not gonna get on the bus, you won’t get anything at the end.” It’s not a state that people who go in to do their critiques are necessarily ready for. It’s not a criticism of the critique people [laughs]. But in all honesty, if you’re not ready to be manipulated, there’s no point. Y’know, ask for your money back.

You’re being told that we’re going to manipulate you.

Moulin Rouge! is bold even from frame one: the big red curtain even before the Fox logo, and then the tiny conductor leading the orchestra as the curtains part and we see the logo...

And from moment one, you’re being let in on the deal. You’re being told that we’re going to manipulate you.

You have to bring something of yourself to observing any art. And sometimes we reveal more about ourselves through what we react against rather than what we claim to love.

I’ve only got one concern. It’s not the war between the fifty percent who defend what I do and the fifty percent who attack it. It’s that the people that need Strictly Ballroom, or who need Romeo + Juliet, or who need this film, are caught in the crossfire. I’m not saying, like, we’re here to save the world, but there are audiences that need theatricality rather than naturalism to be touched and feel. I don’t want them to get caught in the crossfire. And it’s not like the viewpoints are fixed from the time films are released. The rewriting of the history on Romeo + Juliet is quite staggering.

Salon’s review from the time of the release of Romeo + Juliet calls it “garish junk” and goes on to say, “It takes a special kind of idiot to screw up ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ but then Baz Luhrmann isn’t your garden variety idiot.”

The great thing about that is that it is so staggeringly humiliating for that critic. If you live by the critique game, you die by the critique game. On the other hand, a very famous American critic came to me and apologized for his review of Romeo + Juliet. In a film class he’d been teaching, he had screened it and a different view of it emerged.

Maybe it’s naturalism rather than theatricality that’s the unnatural state.

Just show me a musical where you’ve had naturalism in the plot structure. There is a reason why we reference very directly Emile Zola’s "Nana" and "Lady of the Camellias" and "La Bohème" in Moulin Rouge! They are all drawing on the same, recognizable, well-worn story structure.

It’s not that you expect people to go, “Aha! A beat out of Nana.” I expect them to recognize a story about a middle-class boy meeting a prostitute who’s dying of consumption and that what follows is going to be a tragic story. Shorthanding gives us poetic resonance and that’s valuable, y’know. That’s what’s really important.

There’s the bromide that clichés persist for a reason.

Well, cliché and myth are basically a picture of our condition, and they allow truths to appear.

Let’s talk about something even more obvious. You like to re-purpose popular song.

In terms of trying to create a musical language that works now, there are two points to make. One is that it’s quite an old idea. When Judy Garland sings “Clang-clang-clang went the trolley” in Meet Me in St. Louis, the period is 1900 and she’s singing 1943 music off the radio. This helped the audiences of the time to get inside the character and the story, to understand a different time and place through their own music. The second thing is that it’s a basic rule of musicals, that the audience have a pre-existing relationship with the music. “White Christmas,” for example, is sung in two or three films, at least.

Were rights issues tough?

I had to meet with publishing companies. They think, “My God, this is a new way to use our catalogue music. This could be good!” Some of the people who wrote the music we used are friends of mine, like Bono, y’know? He’s a good pal. Others, like Bowie and Elton, I just had to meet with them and go through what I was doing and they all loved the idea. “My song being used in a musical? Now that would be good.” Because these people would be writing musicals if we were in the 1940s now. They were very, very positive.

Any you couldn’t get?

Yes. Cat Stevens’s “Father and Son.” It was sad, because it was a great scene. At the beginning of the film, we wanted Christian’s dad to go (growling the lyrics), “It’s not time to make a change, just relaxxxx...”

Did you approach him?

No. In fact, he’s almost impossible to meet with. We dialogued with his brother and, look, I respect why he rejected it. It was on religious grounds, because Christian and Satine are not married. So it’s really simple. I completely understood that, but he was the only one.

Rodgers and Hammerstein let you have a lot of play with The Sound of Music.

They were fantastic. In fact, they have been historically like that. They’ve got this really groovy, swinging board and they’re really, like, “Yeah! How can we get this music into a more interesting and modern context?” In an early script, there was a moment where Toulouse says (Luhrmann adopting the character’s thick-tongued lisp), “Lotth of healthy Bohemian outdoor thex! Rolling in the thnow!” He was describing the show to the Duke, and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s board wrote back that they really liked this idea and that they particularly liked the “lots of Bohemian outdoor sex” line. Which, unfortunately, I had to cut... So, y’know...

In a way, Moulin Rouge! is one long, unrelenting set piece. Artifice, unrelenting. So what about Toulouse’s line, when he spits out at the Duke, the financier of Spectacular Spectacular, “I am against your stupid dogma!”?

Yeahhhh... That came up when we were in Cannes. An army of people came up and said, “We got your wink about Dogme.” But in truth, really, we didn’t. Lars and all those guys, y’know, we’re all distant cousins. We’ve watched each other’s work for a long time and Bazmark has its own dogma.

So your Dogme is your line about Red Curtain Cinema?

Red Curtain Cinema, yes. It is audience participation cinema. It is a cinema that demands of the audience that they participate. It is theatricalized cinema. It tells very common stories where you know how it’s going to end from the time it begins. It utilizes devices to wake you up: music, iambic pentameter, whatever. You’re involved. That’s the philosophy.

But you’re not espousing it for anyone else?

No, no. And I don’t think the Dogme guys are that serious about it. They’re not saying, “All films should be like that.” It’s kind of like a club with a particular way of thinking.

I’m sure there are people who might think that I must be a zealot. But my view is: you have a story, you have a notion to convey it, you invent a cinematic language for it. Moulin Rouge! is the last Red Curtain film I’ll be doing. The next piece will have a completely different cinematic language. When you start believing that “there’s only one way to chacha-cha,” you’re in trouble. When you start listening to people who tell you that there’s a rulebook about art, you’ve got a problem. You must have your own way of telling your stories. When David Hockney, who’s a great fan of our operas, talks about painting, he says, “It’s my way of seeing.” We always have to find our way of telling.

What killed the musical?

Action is king right now. Right? There was a time when musicals were king, and when sword-and-sandal was king. Then we hit a period, the 1970s, and it was all about extreme reality, Mean Streets, y’know, reality cinema. It was about filmmakers destroying the artifice of their parents. I mean, Martin Scorsese’s parents were into musicals. The circle just goes round. Stories don’t change, just how you tell them. And what we are doing, I think is a kind of reaction against super-naturalism.

As we were winding down, I told Luhrmann about some footage I had shot a few weeks before, intending to reduce the idea of the musical to its essence in ten minutes or fifteen. I described what I had and he perked up with a sweet jolt. He looked at me as if I had asked whether the sun comes up in the East, then proceeded to lay it down like a red carpet.

“All right, it’s true and it’s myth, it’s boy and girl, the boy…”

It’s a song, it starts with a song… Luhrmann stands, again places his jacket over the back of his chair, “The boy sees the girl, he dances forward, she moves back, he hesitates, she dances forward, then around him, then he matches her moves.”

Cha-cha-cha, tango, repeat? “If your story measures the movement toward and away from love, it’s a song, it’s a musical,” he said, waiting for my reaction.

“Boy? Girl? Dance? They’re searching for love? Perfect!”