Movies Of Late

I Lost It At The Chat Prompt, You Hurt My Feelings, Master Gardener, Joan of Arc Does Joan of Arc, Fehér’s Twilight, The Man Who Fell To Earth

A diversion on artificial intelligence, Kael, Sontag, quarter-billion-dollar man David Zaslav, James Schamus and other things here:

Commerce; evaluation. Criticism; quarterly returns to stockholders. It’s a muddle! Critic Godfrey Cheshire composed an epic surmise, “The Death of Film/The Decay of Cinema” in 1999 as James Cameron and George Lucas and their financiers facilitated the transition from light passed through 35mm celluloid strips to video projection: “[T]he overthrow of film by television–which is what this amounts to–will be related to a dissolution of cinema esthetics and the enforced close of cinema’s era in the history of technological arts.”

Sontag again: “Cinema, once heralded as the art of the twentieth century, seems now, as the century closes numerically, to be a decadent art.”

Now it’s 2023. Nearly a quarter-century. Who’s as august as Sontag, who should I ask for the hottest take today? I offered a quick question for the chatbots at Google’s Bard offering: “What would Pauline Kael say about screenplays written by A. I.?”

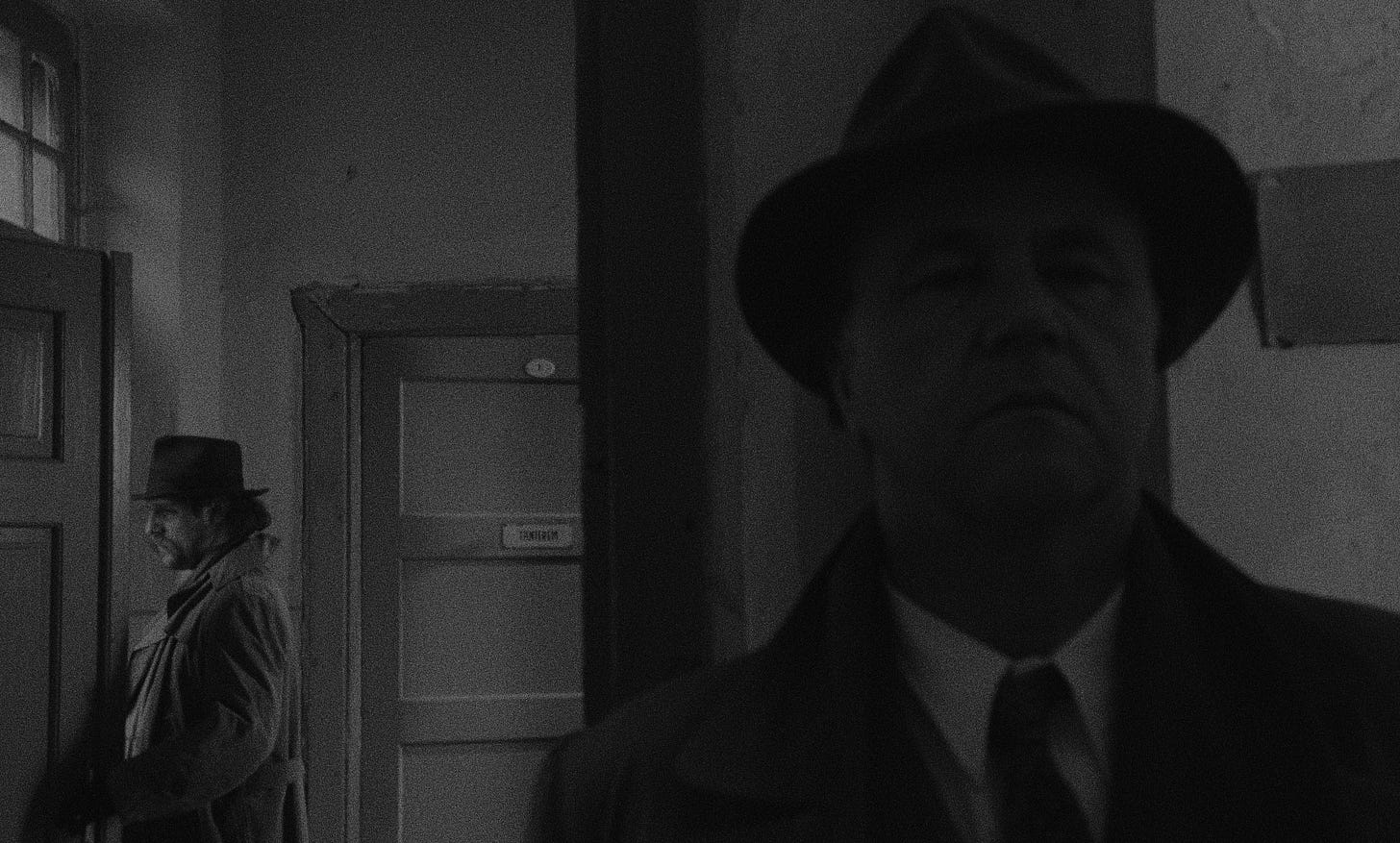

György Fehér’s Twilight is great, granular gloom:

The detective’s existential quandary in a minimalist landscape is illuminated by Fehér’s 1991 statement while picking up a few prizes on the festival circuit: “I want to show to what extent the search for justice stands in ridiculous contrast to the eternity of nature. Meanwhile, it is precisely this search that I am so fascinated by.” Fehér’s film is a serene experience: we are made as much of mist as we are of mysteries.

Paul Schrader’s Master Gardener:

Visual elements are simple yet often bold: in the master house, there is wallpaper patterned with chalked jellyfish on baize-green ground; the flowers are presented as pinpoint splats of color like squibs detonating in a shootout. There is a dreamt image of a highway’s verge by night blossoming and turning to garden, leaving civilization behind, racing into a bower of bloom. There is also a shot lifted from one of the most beautiful of Schrader’s touchstones, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970). Maya sits on a bed in an unadorned motel room, realizations washing over her in the physicalized form of the light from headlamps of a passing car turning through venetian blinds, stroking, striating, elevating.

Joan of Arc’s Tim Kinsella on Joan of Arc doing Joan of Arc:

I think part of why JOA was able to persevere for so long is that we evolved into having a pretty expansive practice. We all enjoy all kinds of music and it was always a great thrill for us to work new elements and gestures into what we do while not losing track of our core. This project specifically is a way for us to indulge our interests in twentieth century minimalists. It’s exciting for us to use the familiar sounds of rock-band instrumentation—guitars, bass, drums—and apply them to forms that usually employ different tonality.

Nicole Holofcner’s You Hurt My Feelings:

Nicole Holofcener’s You Hurt My Feelings is a tender, testy feat: a fine, fierce comedy that moves at the pace of irritability without cataclysmic detonation, only deepening disappointment. Plus, a little bit of money and a lot of neuroses go a long way. Holofcener’s movies move gracefully from minor-key moments and momentary mortification. Her latest feature stars her capable muse, Julia Louis-Dreyfus (Enough Said) as a New York City writer who can’t get the hang of her new manuscript; playfully eavesdropping on her therapist husband, she overhears him saying that he really hasn’t liked any of the drafts he’s read. Social structures crumble in this comic kammerspiel.

The Man Who Fell To Earth, shown on 35mm in Chicago:

Roeg, a time-slipping editor who began as a cinematographer, knows red from blue, red sand from blue sky from green water from red blood, knows the difference between Bowie’s milk torso and Rip Torn’s fishbelly-white gut. The Southwest is pinioned against Manhattan of that moment, and Roeg gets more from his juxtapositions than even Terrence Malick in The Tree of Life. But both these dream-state editors work with abstraction and the very concrete: objects and glances and reactions are given light-and-death weight. Every bit’s abstract and so very concrete. Objects like white telephone handsets and multi-pane mirrors anchor glances and reaction shots. There are echoes of then-fresh color still photographers like Stephen Shore and William Eggleston, with Shore’s blank stares at common color and Eggleston’s awestruck glances at the essential character of banal juxtapositions within the frame, but Roeg and cinematographer Anthony Richmond are fleet, liquid, never to be pinned down.