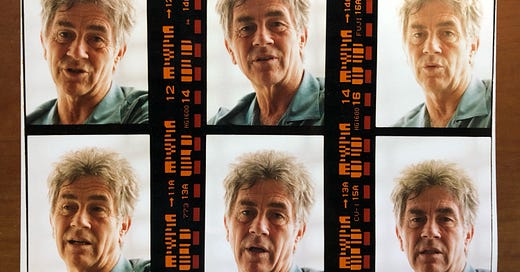

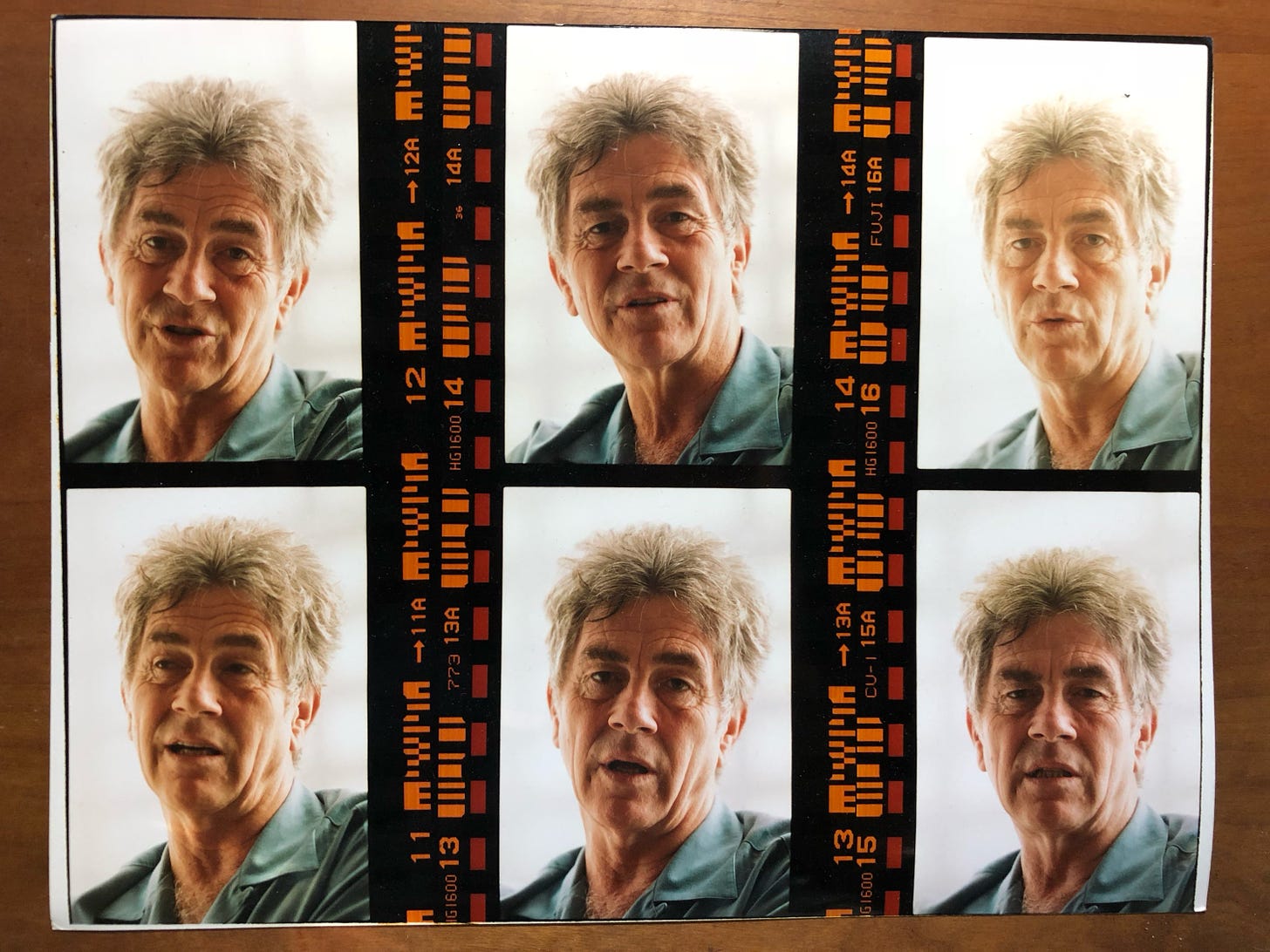

Hampton Fancher was sixty-one when he made The Minus Man, his serial-killer directorial debut, released in 1999. We spoke in Chicago on a high floor of the Ritz-Carlton—glistening Lake view, etc.—when the film was released. It was early afternoon he wanted to talk off-the-record a little before starting, he had disliked the previous interviewer and was ready to open another of very chilled white wine. He wanted to give me the answers he had denied the prior guy, including about being Jim Morrison’s neighbor and being the one who had to deliver the news down the block when the musician had died in Paris. (He tells that story, and many others, in many other places.)

Most people know the name Hampton Fancher as the name above David Peoples' on the script of Blade Runner, or perhaps on the script of 1989's The Mighty Quinn. But Fancher, who began as an actor on television programs like "Maverick" and "The Fugitive," has made a living as a screenwriter for years.

He made his directorial debut at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival with the The Minus Man, based on the novel by Lew McCreary. Weirdly laconic, it follows the travels of drifter Vann Siegert (a slyly charming Owen Wilson), a gentle blank of a serial killer at the center of its purposely (and purposefully) flat narrative. It's bracing to find an unbroken spirit like Fancher, still talking with the ideals and the sprawling notions of a much, much younger man. Beyond the stylization of the drama, Fancher also demonstrates an ear for poetic language, flat yet flowering, capturing some unspecified damage in each character's way of speaking. After talking about recent films that had dug into the dark recesses of men's minds, we turned to voice—the voice of a character, the writer's voice behind the characters' voices.

So—voice.

One thing you might try to plant in yourself is that there are various ways to do things. The ideal of finding a voice might be something unconscious, it might be someone talking in some bar that fulfills that. But when you find that voice, they begin to talk like that in your head or on the page or even out loud, then it's unstoppable. You can't get in its way too badly unless you're a fool or shooting up or something. Somerset Maugham used to sit down and write his name until he hated himself. He'd fill up three pages, looking, looking, trying to find what he was going to write about.

There are times when you realize you have a theme, but the voice of the characters is elusive.

The inner voice is very primitive often. It starts with something simple. But once you get that voice, then you don't have to worry about being arbitrary, the intellectual or conceptual aspect of it.

What sets the voice off?

I think it's unconscious. It takes a lot of baths or typing. All of a sudden, it's just a phrase or a name, you laugh, you get excited, then you start railing. It's just a question of application, consistency, discipline.

Do you write in simple language?

I used to write overly rich, almost baroque language. I got sick of it. I read a script, Walter Hill's draft of Alien. Man! That and early Elmore Leonard. I still write rich sometimes, but for the most part, I like to write lean. The trick in screenwriting is to get the job done fast. Even if you're being opulent. I write ten pages to one page. It might take me four months to write those ten pages.

Polishing and tweaking or finding the thread?

Polishing and tweaking has to be done fast. No. It's permutations, finding the voice, the next day, saying, "Fuck! That's not it." Then when you get into stuff, you run. I literally am dumb, it takes me a long time to find those voices. The Minus Man was an exception.

You've described the spooky calm here "affectless" but the dialogue is flat, yet often poetic, as well. "I’m not even thirty and I've got six things wrong with me." "I used to live there once, for a while." You can take those in isolation and they sound like Terrence Malick. But as you watch, it's more like, who is this goofy guy? He's saying strange stuff.

If one responds to that, those qualities, I'm lucky. I felt lucky writing it. I remember the bar scene, the first thing I wrote, in about eight minutes, not like me at all. It wrote itself. I couldn't keep up with myself. When she said that, "I'm not even thirty..." I called up Lew and told him, I said, can I read you something? I've departed, I want to give you an example. I was pretty proud of it, too. It just happens. I think what happens is it's probably one's day. It's a word. The idea of having something wrong with you? I probably heard somebody say that. And when she said that, I knew I was in gold. She was alive.

Overhearing something and twisting it: Purposeful mishearing.

That's been my life. I play with that a lot. I think it's susceptibility.

Leaving yourself open?

If you're sensitive, or sensitized toward other people's rhythms and ideas, usually something quixotic or funny will rise up. They're buried there. Directing to actors is also the same for writers: A director gives an actor an idea and then the actor takes that idea and grows a new plant from it. The same thing happens with overhearing and observing. Things, unbeknownst to you, will pop out.

And it's more fertile than staring at the blank page. You've made a living churning pages for years, but only two other movies got made.

Scripts I've written. Lots of 'em. I'm not prolific, but there are some I own, but studios own most of them. My most promising things, I can't get. Too much money has been spent on them already. Warner Bros. has a pretty interesting story of mine, but they have a policy of not putting a script into turnaround. You can't get those things away.

Making your directorial debut at Sundance at sixty-one is unusual enough. But it sounds like you've had a good life, nothing to regret.

I know what it must look like out there, "What have you been doing all this time?" There's a seventeenth-century writer who said, "They who would be young when they are old must be old when they are young." I was pretending to be old all my life until I got to be about thirty. So I don't feel old exactly. I know I have only a few years left, but the challenges and the rewards are still the same. I was probably a fanatic when I made my first short at twenty, an asshole probably. There is something that comes with age about humility and not being threatened by being wrong. When people would tell me something was wrong, "Fuck you! Get out of here!" So who would want to tell me? How could I learn anything? That's a good part of age. The confidence that allows one to make mistakes.

There's a calm and unflurried visual style here. Older directors with experience do that, but first-time directors usually show off.

After I saw Run Lola Run, I said, I have to make a fast film! I used to try to make fast things. Eight frame cuts and stuff. But Minus Man had a placidity about it. I wanted an almost passive approach to the whole thing. To be tranquilizing. A deadly lullaby.

Along with Owen Wilson, the cast includes Mercedes Ruehl, Brian Cox, Sheryl Crow, Dwight Yoakam, Dennis Haysbert and Janeane Garofalo. The Minus Man Blu-Ray from Kino Lorber. is a fresh HD master, from a 2K scan of the 35mm interpositive and includes a new audio commentary by Fancher and producer Fida Attieh.

In early 2019, Fancher released a slim column of aphorisms on screenwriting, which I reviewed at Newcity.

Hampton Fancher’s name appears on but a fistful of produced screenplays—including Blade Runner, The Minus Man, Blade Runner 2049— but his legendary life is rich, captured in part in Escapes (2017), Michael Almereyda’s captivating experimental interview documentary. Fancher, garrulous, greedy for experience, is, among so many things, a flamenco dancer-turned-actor-turned-screenwriter, an all-round beast of curiosity.

I first met Fancher when he was a hale sixty-one, and had made his directorial debut with “Minus Man.” Here’s a sample of that exchange before whiffing his carborundum-strength dream prose and scheme advice. “Scripts I’ve written? Lots of ’em. I’m not prolific. There are some I own, but studios own most of them. My most promising things, I can’t get. Too much money has been spent on them already.”

Drawing from courses he taught at NYU and Columbia, Fancher’s “The Wall Will Tell You: The Forensics of Screenwriting” (Melville House, 80 pages, $15) is a punchy pamphlet introduced by Jonathan Lethem and packed with incantatory aphorisms about screenwriting, process and result, that slip-slide from poetry to passion, from carpentry to fever dream. “I’ve learned a lot from Hampton over the years,” Lethem writes, “and most of all when what he had to teach me came in the form of a baffled admission that he had no fucking idea what to do from one moment to the next except live, write, exist and love. ”

A pungent parallel to Robert Bresson’s spare “Notes on the Cinematographer” (out-of-print but readily available online), fumes of Fancher passion rise like cool, perfumed wine. Translated Bresson includes “Make visible what, without you, might perhaps never have been seen,” and “The most ordinary word, when put into place, suddenly acquires brilliance. That is the brilliance with which your images must shine.”

Fancher’s words read instead like those of a man who acted in “Gunsmoke” and “Bonanza” and beat down the 1960s and tore up the 1970s and kept it going into a new century and was Jim Morrison’s next-door neighbor in the Hollywood Hills once upon a tale. They’re not koans, nor “Oblique Strategies” in the style of Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, but they’re worthy rabbit punches of experience, both practical and philosophical: “Music, painting, acting, architecture, fucking pottery, even screenplay writing; in all art, an element of surprise is essential.”

“Above all, don’t fucking digress into anything intellectual. It’s action you want. It’s a pinprick, even. Keep it simple, keep it felt. Language is secondary. But it also isn’t—don’t be stupid, write sharp.”

“Don’t give characters flaws that you don’t care about, that you don’t take seriously, or that you don’t think are fun.”

“What you are trying to learn cannot be taught. What you learn is by teaching yourselves through trying. You have to become better than your teachers or your teachers are shit.”

And, yes, of course, “A screenplay is the bones of a poem and the poem is a movie and the movie is a dream.”