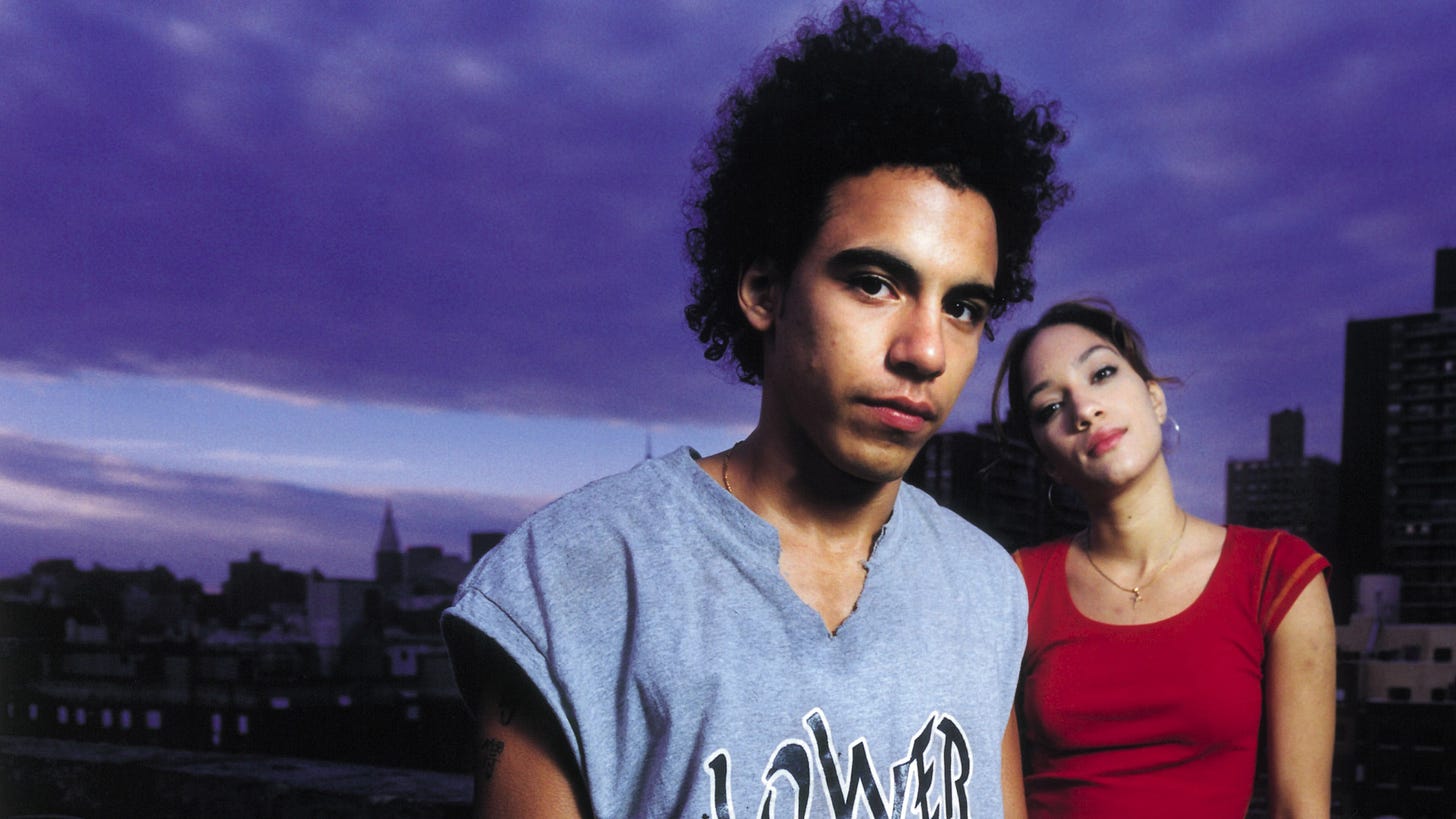

Raising Victor Vargas

A deadline review from Sundance 2002 and a contemporary interview with director Peter Sollett

Raising Victor Vargas debuted at Sundance 2002, and was introduced at an October screening at the Academy by co-writer-director Peter Sollett and co-writer Eva Vives. Sollett and Vives’ filmographies have been bountiful in the decades since, but Raising Victor Vargas was one auspicious debut which I immediately loved. (It’s streaming now on both free and subscription services.)

I wrote a deadline review of the film from Sundance, and later, an interview with Sollett. (A fifteen-minute video case study with Sollett on its making is here.)

Peter Sollett’s Raising Victor Vargas is the kind of sharp, tender, precise small wonder that says more than most epics. Drawing on his superb 1999 short, “Five Feet High and Rising,” which won prizes at Sundance and Cannes, Sollett has created a glorious, full-blooded, oft-profane, fully inhabited microcosm of life and love among teenagers on New York’s Lower East Side. Using mostly nonprofessional actors, Sollett tells the story of Victor Vargas (Victor Rasuk) and his family: a younger sister, Vicki (Krystal Rodriguez), a younger brother, Nino (Silvestre Rasuk), and his cranky, endlessly put-upon old-school Dominican grandmother (Altagracia Guzman). At his most senselessly self-assured, Victor works the streets as a teen Latino “Roger Dodger” but at other times, he’s just the cutest dork on the block. He likes to think he’s Casanova, but he’s actually still a kid, with bravado, the adrenaline tremor behind teenage hubris and self-regard. “Juicy Judy” (Judy Marte), the girl he longs for, sees through him, but the layers of that contemplation are patiently revealed.

It’s the essential hormonal equation: discomfort and desire, inextricably combined. Raising Victor Vargas is a rare contemporary sample of comic neorealism, a small movie that manages to quietly capture with looks and smiles the same things that required operatic conflicts in movies like Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers. Another great trait on show is Sollett’s immense compassion and empathy. He originally wrote the script to be set in Bensonhurst, the predominantly Italian and Jewish neighborhood where he grew up. It began as an autobiographical project, but he couldn’t find the type of actors he wanted. Sollett and his partner Eva Vives posted notices in their East Village neighborhood, and most of the kids who responded were Latino. While it began as an autobiographical piece, Sollett worked for the two years between the short and the feature with the performers, observing them, asking about their lives, and bringing the fruit of their friendship to the screen. Raising Victor Vargas shows affection without sentimentality and it also shows a wry acknowledgment of the complexities of a family’s conflicting desires. (It’s also one of the great portraits of how teenagers tease one other.) The film benefits from an instinct for the documentary truth of directed improvisation, which is then sculpted through assured editing.

Other technical aspects shine, too, including the camerawork of Tim Orr (George Washington, All The Real Girls), in richly grained super 16 images, replete with jittery, itchy sneak-zooms that tickle in ever so much more tightly on a good instant of performance. Other times, the camera holds with infinite patience and love, letting a moment between the actors play and play and play. There’s brilliant sound recording as well. Listen to the voice of actress Melonie Diaz, who plays Judy’s seemingly mousy but actually beautiful best friend. Every sly intonation of her almost-a-whisper voice comes across with rich nuance.

The performances are impeccable as well. There are close-ups of the confounded grandmother that capture what it is to love, fear, fear for, and be wounded by one’s family. And I think Victor Vargas may have the best joke about masturbation of all time with a sly reference towards the end of the film. I’ve seldom laughed so hard. This is the sort of movie that I shouldn’t compare to the work of others (such as Mike Leigh and Ken Loach). Raising Victor Vargas is perfect on its own terms. I laughed, guffawed, cried, wanted to see movies just as good, wanted to make movies of my own. The 26-year-old Sollett and his collaborators prove themselves to be masterful miniaturists and also that there’s no subject larger than the beating of the human heart.

Talking to the quiet, soft-bearded young director over the weekend, I wonder what could possibly hold over to his next movie. “The beautiful and intimidating truth about what I have learned in my last five years of filmmaking is that there are so few things written in stone. Each movie needs to made on its own terms.” Of working with non-actors, he says, “Every actor needs to be directed with a vocabulary unique to the particular relationship you have with them.”

The movie has a serenely confident air, but never seems predetermined. “ I greatly admire filmmakers that appear confident in their moviemaking,” Sollett says. “I sometimes dream of what it would be like to wake in the morning—whether it be to go to my desk or the set—and have all the answers. But I don't think that exists. I think that a confident filmmaker is someone who is confident in themselves that they are capable of utilizing their resources to make the best film possible, even under a great degree of pressure.”

The camera’s jittery. The characters tempt. And Bergman, wasn’t it Bergman who said cinema was a close-up of the human face? Sollett cops to a few influences. “Cassavetes, Fellini and Bergman,” he says. “I look at the films of these three directors and I see three filmmakers achieving a single goal, but utilizing, each of them a completely distinct cinematic vocabulary. What do I think they have in common? They are humanists. At their best they are mapping emotional terrain not charted anywhere else. They look deeply into their characters, weather they be deep or shallow and expose them for their best and worst they have to offer. And they are honest! So honest! So frequently their relationship to the world around them feels so positive. They are for the people! Human beings, life in general is something of value in their films. People are more than a single objective or an obstacle or an object of sexual desire in their films. I admire their respect for humanity, even when they acknowledge that sometimes we harm each other unnecessarily.”

Shooting a few hundred hours of footage, treating a feature like a documentary, can make a mess that’s hell to untangle. “Certainly. I did everything that I could to look ahead and try to make things easier on myself and my editor Myron Kerstein but sometimes I did paint myself into a corner. We shot coverage, but not an irresponsible amount. Our shooting ratio was about 15:1. Not bad.”

The reviews out of New York are ecstatic. Is that gratifying? “To a certain degree, yes. One of the reasons I’m making films is to communicate with people. I could never put into words what I am trying to communicate in Victor Vargas. Reading a good film critic can tell you what his or her relationship to the film was. How well did we communicate this? How deeply into the layers of the writing and performing did they see? And why? That's the level that I am interested in reading. So often a review reveals more about the critic than anything else, and that can be interesting, too!”

Sollett keeps up with other filmmakers and their work. “Adaptation, About Schmidt, Punch Drunk Love, I have a different relationship to all of these films, but perhaps what they have in common is that these filmmakers are exposing themselves, their world views and doing it in such a way that we all have access to it. The other day during an interview a journalist was clearly trying to provoke me to say something condescending towards studios and studio filmmaking. I wouldn't do it. Perhaps I’m focusing on this how these filmmakers have navigated studio waters through their filmmaking as opposed to an examination of their expression or individual voice. It's probably because I am in awe of them and I am trying to figure out my own next move.”