Ready when you're Abel

Talking The Addiction with Abel Ferrara and Lili Taylor

Published in a slightly different form in October 1995.

Middle of a sunny autumn afternoon: Abel Ferrara hovers in the heart of a Toronto luxury hotel, ashen behind sunglasses and a battered BAD LT baseball cap, reflected several times over in front of the mirrors that flank a bank of elevators.

While resembling the addictive personalities of his new good-grapples-evil black-and-white vampire movie, The Addiction, Ferrara has several versions of himself to choose from. The particular one I'm talking to is a lanky, sleep-starved Italian American Noo Yawker, who expresses himself in muttered hipster patois, a willful anachronism, playing the role of God's honest man in the indie-film wilderness. His answers veering from intensely focused to cheerily cryptic. Ferrara slumps in a chintz-covered lobby chair. He's taken fourteen hours off after the first week of shooting a new gangster movie [The Funeral], set in 1935, to talk about and introduce this one. He takes off the hat with the frayed bill. Harvey Keitel’s character would also wear out a hat like that, I say. Even at his worst moments. “His worst moment? Heh. The LT was rockin’!” Ferrara says.

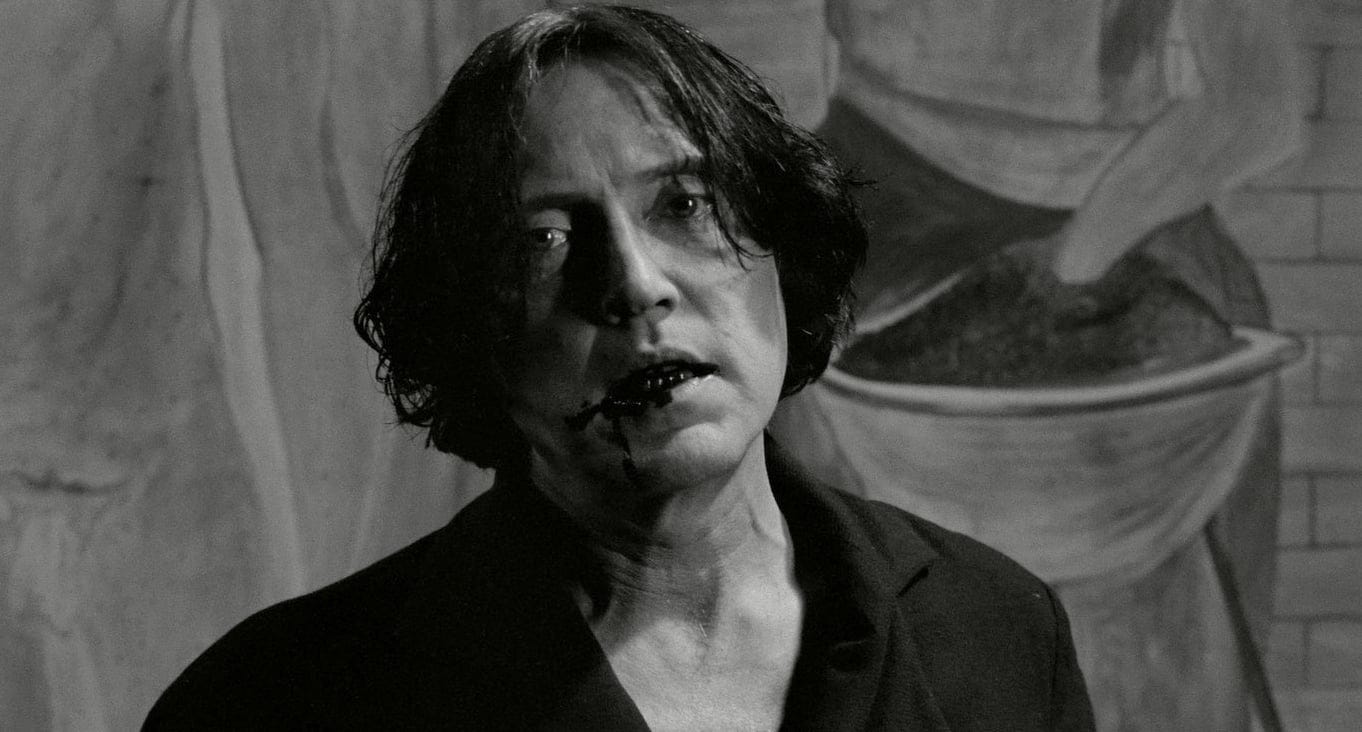

The Addiction stars infallible, ineffable Lili Taylor at her formidable best, as an NYU doctoral candidate in philosophy who discovers bloodlust is the answer to many of her intellectual quandaries. While the characters drench themselves in grad-school chatter, the milieu is still recognizable as Ferrara's ultra-serious, ultra-perverse New York and its congeries of overlapping demimondes.

Is The Addiction a distillation of the themes that were so bold in Bad Lieutenant?

"There are certain basic things that aren't gonna change, whatever the genre of the film, or the time period of the piece, or the characters," Ferrara says after the first of many long pauses. "There are certain life struggles, coming to terms with the world around us, that's not that different from any artform in any given era. Painting on cave walls, even. It's funny about the vampire, it was very much, a story that's been told over and over in every culture around the planet... Probably in other cultures on other planets! Like Bertolucci says, 'The bird always sings the same song.'" Ferrara drifts for a moment. "The robin sings the same song, heh heh."

While there's a pleasing amount of genre-satisfying grue, The Addiction (written by longtime Ferrara collaborator Nicholas St. John) is best as a terse, blunt look at how good can exist, even triumph over evil. It's interesting, I suggest, that the vampires here are smart enough to realize the drives behind and limitations of their dilemma, of the different between theory and practice, thinking and living—

"Yeah, right!" Ferrara interjects, waving his large hands, pointing his sunglasses toward me, "How far can the intellectual side of life take you? I mean, you're missing the spiritual. What's the intellect without the soul? The mind and body can't survive alone."

Why black-and-white? "It was to go back to our roots. Simplify things. We always wanted to get back to black-and-white. We're constantly trying to minimize the color scheme. As much as they say it's not black and white, it's shades of gray, at least on the grayscale, um, we did it pretty much. At the beginning of our careers, it was black-and-white, that's what's worth returning to. I think it focuses onto the story, onto the eyes of the actors. It focuses on things that are important. It's not somebody's sweater standing in the background."

Lili Taylor always has remarkable presence, but her performance here is piercingly good. "She was introduced to me, just out of the blue," Ferrara recalls. "It wasn't specifically about The Addiction. We had that script. When you have material like that, if you don't have an actress, you don't have anything. It was just a chance meeting. I didn't know her work and she didn't know mine. The result was what you saw." He nods. He keeps nodding. “Heh-heh.”

"Clearly, Abel is an interesting director and I like the way he works,” Taylor says a little later that day. “And female roles like this are few and far between. It was just perfect for me, perfect—shoot in New York, shoot very independently. Then the content I find very interesting, the whole dark night of the soul, the whole vampire theme with the addiction and denial that we all have."

What kind of directors are best for Taylor? "It helps to work with a director in rehearsal. If you get a good two to four weeks, and you're beating out the script together, when you come into the filming, you each know exactly the essence of each scene. Then it doesn't become a superficial mechanical stand-there, do-that, you have a foundation. You're already in sync, already dancing together when the shot starts."

Is that Ferrara's knack? "What's great about Abel is his emotional involvement," she says. "I really felt he was just viscerally with me, as if he was vicariously living it through me. It was sometimes a problem, because he talks a lot through the takes, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, go, great, with you, with you," It sounds like how silent movies were made. "So in the editing you have to do a little bit of looping! But as an actor, it really helps."

Does Ferrara talk about the ideas behind the story? "Yes. The more I know where the director's coming from, the more I can be of service to them," Taylor says. "So we talked a lot about the themes, and I'm glad Abel wasn't afraid to talk, he'd get deep in his own jazz-cat way. I love his beatnik kind of language. And he'd never get pretentious. He'd just talk in a cool, deep way and in fact that's why they wanted to make the character a philosophy major, so you could show that pretension, that headiness. Until you live it, that talk is just talk, it's cheap."