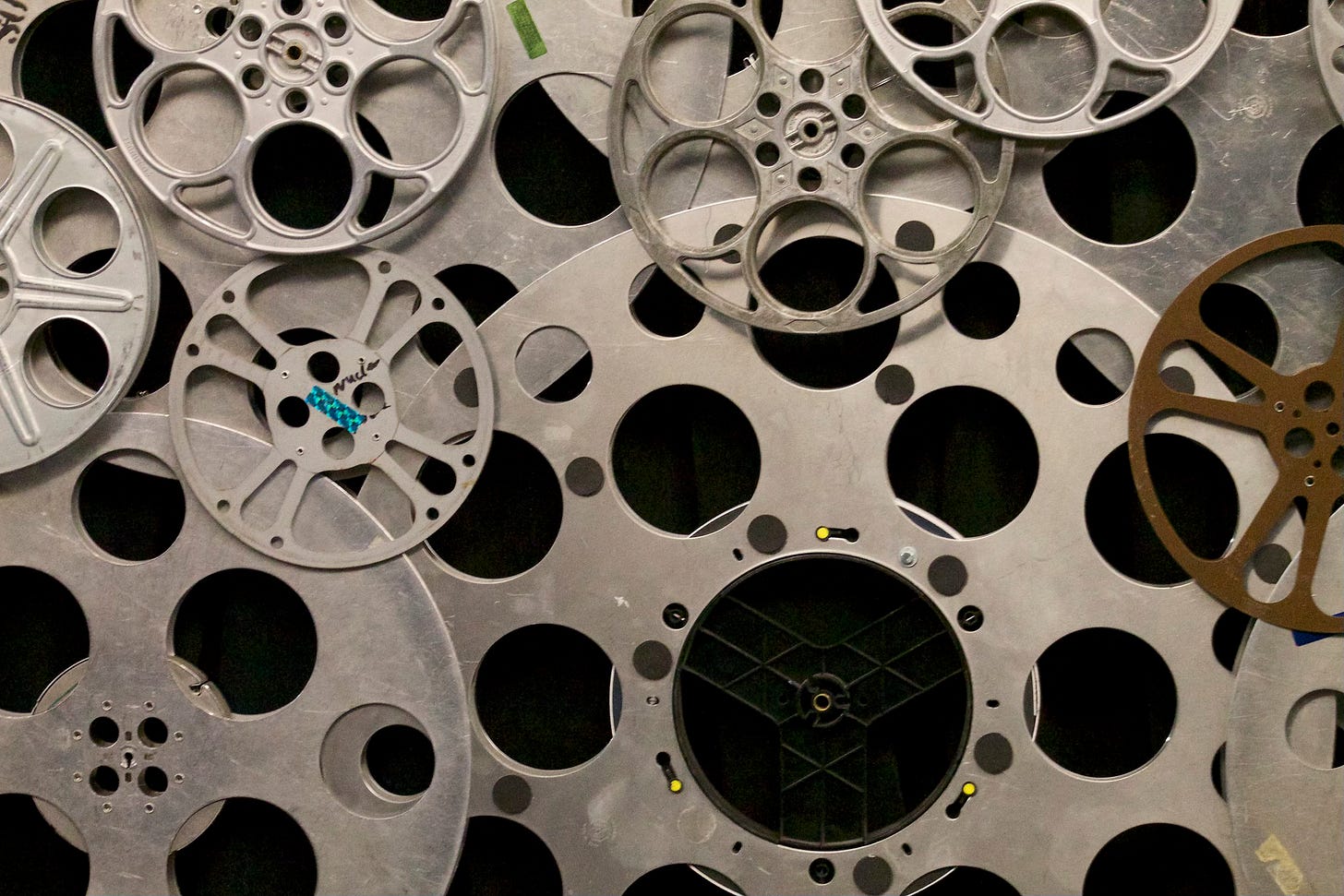

RIP Cinema Scope At 97 Issues; Sundance in 2001

A Sundance 2001 festival report for Cinema Scope on the day the essential cineaste rag folds up shop

Cinema Scope, the indispensable Canadian film quarterly, has passed at issue 97. Publisher Mark Peranson provides the scoop with the customary tossed-off verve of his Editor’s Notes. The cover of the final issue boasts a cowboy collage by Guy Maddin.

I was a contributing editor for about a third of Cinema Scope’s run, from issue one. Among other things, I got to publish a lot of interviews I still like (including with Neil Young upon the release of Canadian-content Greendale). Here’s a piece from an early issue, trudging past Sundance 2001, after its expiration date, a few months before 9/11.

“Does my pleasure bother you?”: Notes from Sundance 2001

Lining up to go in circles. A refrain in Redford's "Inferno," aka, just another day of slush at Sundance. Movies are supposed to be organisms, not artifacts, but there are moments when the Sundance Film Festival seems little more than a high-stakes glorified trade show shoehorned into a frontier resort.

I'm always enough of a romantic fool to think that I might discover a half-dozen movies in Park City that I like as much as Daniel Minahan's Series 7. It's an electric satire of unreality television, a pre-”Survivor” script about a show in which seven good citizens are selected (unbeknownst to them), given weapons, and are followed by a camera crew through their stalk-and-kill paces. Funny, authentic to the inauthentic devices used to hype human drama on TV, and even touching in spots, it's also savage.

But there's compassion on the slopes as well. Maysles Films is not the only celebrated, or soon-to-be-celebrated documentary production group with work at the festival. But the first film I watched after getting to Utah, Lalee's Kin: The Legacy of Cotton, by Susan Froemke, Deborah Dickson and Albert Maysles, with customarily adept cinematography by the 73-year-old veteran. Maysles, dubbed "America’s best cameraman" by no less an eye than Jean-Luc Godard, watches compassionately the plight of the extended family of Mississippi Delta resident Laura Lee Wallace, or "Lalee." The directorial triumvirate made several journeys south to chart the ups and downs of Lalee's dozens of kids, grandkids ("grands") and great-grandkids ("my great-grands"), whom she toils over all the hours of the day. Her life is genuinely sad, and the chances for advancement for poor, ill-educated Delta residents is illustrated through the troubles of the West Tallahatchie County school system.

Yet she's irrepressible. Lalee's language is compassionate and weary. Her refrain: "I hate cotton." It was hard on the African Americans who had to pick it, and harder when mechanization eliminated those holdover jobs from the time of slavery. As with the best Maysles Films' documentaries: there's so much love shown through the simple act of listening. The subjects tell their own stories. Narration is shunned. "I go through a whole lot. Oh, I go through so much, I cry sometimes, pray sometime, sing sometime. Don't nobody know." She's weary; it's not self-pity. Simply listening can be the most compassionate act of all, particularly to those whose voices are seldom heard. Subtitles allow us to appreciate the poetry and cadence of the dense Delta speech without having to strain for the sense of the stories of their lives. The final images, representing the escape of one of Lalee's brood to another life, are accompanied by a line of great lyricism. What is this young girl anticipating? "See what my future is gonna be like."

Although many journalists and publicists have shorter schedules at Sundance this year, the flock descends on the Shadow Ridge headquarters on Friday. Veterans greet veterans, kisses, hugs and wisecracks. Sit in one place, the indiewood whirl revolves past. "Everyone comes to Ridge," a middle-aged Casablanca-lover cracks.

The festival's first press screening produces a serene gem, Barbet Schroeder's Our Lady of the Assassins. Mature work, in all the best senses of the word, this story of impossible love against the backdrop of teenage contract killers in Medellin, Colombia, is a gem of magical miserabilism. Middle-aged writer Fernando (German Jaramillio, intense and wry) returns to his home city after many years, and he's startled by the near-nihilism of daily life, its random shootings and absurd events. He meets a teenage boy, Alexis (Anderson Ballestreros, movie-star-striking yet a non-actor), begins an affair. Violence escalates. Fernando blasphemes, speaks in cynical poetry of what he sees around him. But his lover's impulsive shootings fascinate him: "All these killings are encouraging my own self-destructive urges." The horror of living where life is unlivable is a grandiose spectacle, yet the film is as cool and collected as its characters. "We should indulge every vice to prove we're alive. Virtue is for the dead," Fernando tosses off. Our Lady is one of the great portraits of how the writer talks, lives, and invents the greatness of their romantic others.

After seeing that, I didn’t have expectations for L. I. E. Yet Michael Cuesta's Long Island-set suburban comedy of terrors deserves far more than a ranking in this season's queasy-making tales of pedophilia. Nervy and almost foolhardy, its themes could pass for a variation of Audrey Wells' Guinevere, with an older person using adolescent "awe" to their own pedagogical, seductive advantage. Utterly unsentimental about teenage cruelty, the story is partly about the practice and pathology of pedophilia, inhabited by the great Brian Cox as predatory retired marine Big John (with "BJ" on the vanity plates of his teen-trap 462 Cutlass muscle car). Paul Franklin Dano is also exceptional as the 15-year-old Howie. With only a single line of self-reflection, Big John remains a sympathetic character, despite explicit dialogue that will likely drive the self-serious out in the open. But it's more than another ballad of sexual dependency: it's also about teenagers and their confusion, a kind of L'il Rascals for a cold millennium. Cuesta and co-writers Gerald Cuesta and Stephen M. Ryder weave the contradictions of the characters into fresh and effective drama

Year after year, some of my biggest kicks at Sundance, on screen, at least, come from the World Cinema section. The eye-popping violence of Chopper may be the closest any film comes to the bubblegum rush of past Sundance entry Run Lola Run, but I've seen more than a handful that should counter any trends being sifted and manufactured in dark spaces across Park City (in journalists' minds, I mean). Antic splatter is onsite with Brother, the grandly eccentric Takeshi Kitano's follow-up to the misunderstood yakuka-and-a kid comedy Kikujiro. Returning to the idiosyncratically jittery, eruption-prone style of his great Sonatine and Fireworks (Hani-be), Kitano remains the Lee Marvin of Asian cinema, once more playing the world's most composed sociopath. His newest strands his stoic yakuza amid the drug gangs of L.A., soliciting the likes of Omar Epps to aid him in taking over SoCal crime. Kitano, like few filmmakers, understands the suddenness of violence, or how to inhabit Yohji Yamamoto, rather than merely wear it.

Beautiful Creatures, a wearisome riff on Strangers on a Train, is another post-Trainspotting U.K. attempt at stylish crime and shocking violence, but all that really shocks is its familiarity. Pluses? Rachel Weisz charms as one of a pair of simple, girlish women who fall into transgression while on the run from seriously abusive boyfriends. I like best one wag's curt dismissal: "Shallow Shallow Grave."

Conversations quickly reach serene velocity: everyone's a storyteller, but who's the listener? Roles shift. It's remarkable how much good conversation comes out of even the worst movie--at least if you've found the right compatriots. I'm worried how little nonsense I've heard spoken so far this festival. I have yet to luck into the kind of after-film q&a's that boil down to the old joke, "But enough about me--what do you think of me?"

Reality is a rare enough commodity in movies, but then again, one man's vérité is another man's unplanned nap. I've been thrilled by a lot of documentaries on show, but there are also features that disprove the common assumption that heavy social issues require an approach filled with solemnity and self-importance. After a week of hearing the dreams and ambitions of fresh-faced filmmakers--sometimes on purpose--Startup.com, a documentary about dot.com mania, seems at moments like a pitch-perfect parallel to Sundance. Produced by D. A. Pennebaker and directed by Chris Hegedus and Jehane Noujaim, their cameras trail two high school buddies, a pair of smug, foul-mouthed twerps who pitch GovWorks.com, a site that would connect citizens to local governments, or help you pay your parking tickets, or something like that. Dot-communists dearly desiring the redistribution of wealth into their own Dockers pockets, they can't even get their lawyer to return their call on a day they are trying to get $17 million in venture capital. The tenacity of the camera in capturing the absurd and awkward moments of the pursuit of power and money is as accomplished as in the filmmakers' The War Room.

The hot topic on Saturday of opening weekend was Raw Deal: A Question of Consent, pointed out by several journos as the first press screening of the new Bush administration. Billy Corben's documentary examines a 1999 University of Florida frathouse incident, variously reported as rape and as "clearly willing and consensual sex." The incident was videotaped, and it's included in the film, along with interviews with the parties involved. We may look at the tape one way; everyone in the film has their own divergent interpretation as well. Facts are stupid things, as one former U. S. president famously noted. A companion piece to Startup.com, amply and horrifying demonstrated the arrogance behind a bloated sense of entitlement. Some scenes are so horrible, I didn't look away from the screen so much as the faces of others in the crowd. Self-pity, smarm and prevailing, hard-core degradation marks Billy Corben's film, and it's definitely the work of a young man. It's not a fully accomplished film. There are serious flaws, including a distracting, redundant Michael Moore-style pursuit of a venal politician, yet the presentation of two aggressively different sides to the story, along with the explicit video taken by two members of the fraternity, offers more than enough potent material to spark valuable discussions. Still, I'd be amazed to see if Artisan Entertainment, which snapped up the film, finds a way to ever get it past legal issues and into theaters.

Unnerving on another level, another fine nonfiction entry is Mark Lewis' The Natural History of the Chicken, which alternates images of a chicken factory's production line with oft-comic vignettes of eccentrics with their pet poultry. Lewis' narrative of the life of the Australian cane toad was odd , but I doubt there will be a stranger hour of film, or more chickens, on view here.

Multi-prize winner Hedwig and the Angry Inch, writer-director-drag artiste John Cameron Mitchell's split-personality rock-'n'-roll musical is a consummate confusion of genres, the adaptation of Mitchell's long-running off-Broadway success, a rock opera charting the journey of a 1970s American rock-loving East Berliner whose failed loves strand him in the U.S. after a botched sex-change. Camp yet pinpoint funny, it's Grimm gone dizzy, fluent in the out called rage. Much-performed and long-developed through the Sundance Institute, it's reverent rock pastiche, in an armature of camp sarcasm. Mitchell's direction is only adequate at first, with amusingly indifferent coverage, with slaphappy focal-length mismatches. (There's even a scene shot through a salad bar sneeze guard.) But it's one of those cases where you don't care: Mitchell is charismatic, homely as Hedwig with her galvanized crimson metal-flake lips of flame, but alive with lovely wide haunted eyes, a gratified smile that blooms dimples and a beak that could end a swordfight with a single parry. The bawdy balladry by Stephen Trask is elevated by Mitchell's stirring, soaring voice. And what's in your cocktail, Hedwig? "Oh... Just a little rainwater... and Everclear." Opening for Hedwig was a short that sent tears rolling down my face from thrilled hilarity, Andrew Lancaster's In Search of Mike. An Australian entry, this spirited, fierce, hilarious and maybe even brilliant eight-minute ellipsis of a lifetime of mother-son damage, recalls only the spats and scatological put-downs. Most of the language is gaudily unrepeatable here, but I do treasure mom's "I always thought you would become somebody. I should have been more specific."

I'm fonder of the free-associative pyrotechnics of Philip Gröning's L'amour, l'argent, l'amour, a reverie filled with wrenching, gorgeous images. By turns concrete and elusive, it's a disaffected-boy-meets-hard-girl-go-on-the-run-with-dog story, shaggy-dog Wenders, as much lucid dreaming as narrative. There are jumpcutty touches of Godard and sparks of Carax, but more interesting is Gröning's soundtrack, a treasury of minor chord music of cosmopolitan eclecticism. Velvet Underground, Can, Calexico and Yo La Tengo underscore the film and the camera often takes off down the highway to their melodies, unencumbered by story, lap-dissolving as if high on influenza and antihistamine. A city symphony anxious to hit the highway, L'amour offers a benevolent poetry to its scruffy young characters' bouts of lethargy, indolence and recrimination. It all melts like warm rain on the skin, and the sensation is refreshing.

A late entry, sold out on its first showing, was Happy Campers, a strychnine take on teen horniness, despotism and horniness, the directorial debut of Dan Waters, writer of Heathers and Hudson Hawk. "You take fun too seriously," one camper chastises counselor Dominique Swain, whose perkiness is quickly perturbable. Camp Bleeding Dove is drenched by multiple voice-overs, thick with Waters' love of pop slanders: Swain is brittle and adorable slanging at the love of her summer, "Don't go Breakfast Club on me, bitch." There's even an interregnum in the eye of Hurricane Skippy that suggests Waters is after something like "A Midsummer Night's Dream" if Shakespeare had mastered the lexicon of "suck" and were an adept of rank sexual hysteria. Followers of Waters' wordy wickedness will recognize familiar locutions. One of Hudson Hawk's nastiest lines is echoed by the aside, "Be nice, her mother and father died on that TWA flight that got shot down." In his q&a afterwards, Waters was pleased to report the reasons provided for its R rating by the laconic comics at the MPAA: "‘Rated R for nonstop crude sexual content involving minors, language and drug use.’ There's no way it's a PG-13 and we just have to accept that!"

Ingmar Bergman said cinema is a close-up of the human face, so Bruce Wagner's Women in Film must be cinema itself. A latter-day The Women, drawn from a chapter of his novel, "I'm Losing You," Wagner's second feature showcases his adoration of baroque language and intense invective. Beverly D'Angelo plays a thwarted producer dictating her memoirs to a microcassette; Marianne Jean-Baptiste is a casting director with a blind baby, writing letters to her friend Holly Hunter; Portia di Rossi is a junkie-thin masseuse plotting a book called "The Thief of Energy." A spirited kowtow to the epistolary muse, Wagner's script is a tumble-down rush of language atop language, meta-language and sexual snap and profane pop, with intertitles more like e-mail headers than chapter titles. The performances are surprisingly rich for such a wordy piece, with Di Rossi's mad autodidactic rants, rife with mispronunciations, the most remarkable. Yet D'Angelo's performance—"I sound like a man, worse, an angry man!"±with its bitter jokes and the repetition of self-deluding cant, is rich as well. . The film has a for-unique look as a digital experiment, and one shot in particular seared my eyes: severe deliquescent shadow at dusk as autumn leaves crusted a turquoise pool, colors I've never seen on film. And with all the flesh on display, the result also demonstrates video's opulent embrace of the imperfections in a beautiful woman's features.

"Dream is destiny" is one of the first lines of Richard Linklater's Waking Life. A philosophical cartoon, it is a daring and loopy singularity. More than an experiment, it's a psychedelic breakthrough. Before its premiere, in its first showing before any audience, Linklater said, "Our hard drive was in Switzerland two days ago... How many of you out there are on drugs? Oh good. We'll have to explain it to the rest of you later." Wiley Wiggins plays a young dreamer whose thoughts spiral across the inner lives of seventy-four other characters, and the philosophical monologues of theatrical weight seem like further chapters of the Grand Unified Richard Linklater Movie. Shot with handheld digital video, with eccentric, spacy animation digitally rotoscoped atop, the effect is indeed lysergic and more charming than one might expect. A few years ago, Bob Sabiston and Tommy Pallotta's Roadhead used an early version of the software. Pallotta is producer here, with Sabiston credited as animation director. As in any Linklater picture, there is a hortatory fervor, loving language that conveys large ideas rather than as lyrical speech. The utterly independent spirit of the project—what other movie this year will showcase a discussion of André Bazin and his ideas about "the ontology of time"—is reminiscent of Steven Soderbergh's Schizopolis in its absurdist intensity. (Soderbergh even has a cameo in this picture.) But where Soderbergh's excursions into tiny strange films has led to larger-scale work like Traffic, Linklater's refrain of false awakenings seems a finished thing in itself. Although everyone in his idealized Austin speaks like a fervent 25-year-old filled with knowledge, caffeine and hormones, it is a world, his world, and it speaks to everyone's dreams. Sitting beside a Texan filmmaker, I asked if this was his Texas. Nope. Austin's a whole other place, he said. But, "I think I liked it." A beat. "I have to sleep on it."

Snow, transit snafus: late to a preferred screening, I let the Sundance gods plop me into the next available show, which turned out to be Nobody's Baby. If I ever believed in a Sundance god, I now believe he/she is dead. An attempt to master the moron-comedy of the Coen Brothers' Raising Arizona with the deft sensibility of a Shannon Tweed straight-to-Hungarian-cable vehicle, David Seltzer's low-budget loser is in a league with Tom Schulman's 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag. Skeet Ulrich and Gary Oldman are two skanky, dim drifters who luck into possession of a baby after Ulrich causes the death of its parents, and the jokes appall. A woman beside me brayed at the lamest gags, and I took a good look at her in the dark. I must have been slackjawed, as she sternly reprimanded my rudeness: "Does my pleasure bother you?"

I must have made it through about three and a half heads here, or at least until Mary Steenburgen is given her first glowing medium close up as milk begins to trickle from her nipples under her white tank top, and she is obliged to bray, "Get out! I'm not your fucking milk cow!" Let's leave it to Skeet's words, or Seltzer's, "O Lordy, this is bad."

To worry the Sundance metaphor, let's take the words of Speed Levitch's character in Waking Life, in the style of his customary wordage and warpage: We are all in "a Dostoevesky novel populated by clowns." But they're chatty clowns. The best films at Sundance this year exhibited the act of listening, and listening well, and it's magic. As for the careerists, the doubtlessly-apocryphal money figures flung about remind me of Errol Morris' definition of a movie versus a documentary: "Two zeros!" But that's all over. No more zeros. Sundance, as always, was just the storm before the calm.

Published in a slightly different version in Cinema Scope 6. Edited by Mark Peranson.