SEPTEMBER 2003—Much of a movie like Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation resists explanation, since its magical, melancholy moods are a triumph of image, music and performance, with lockstep plot and suspense a distant, superfluous concern.

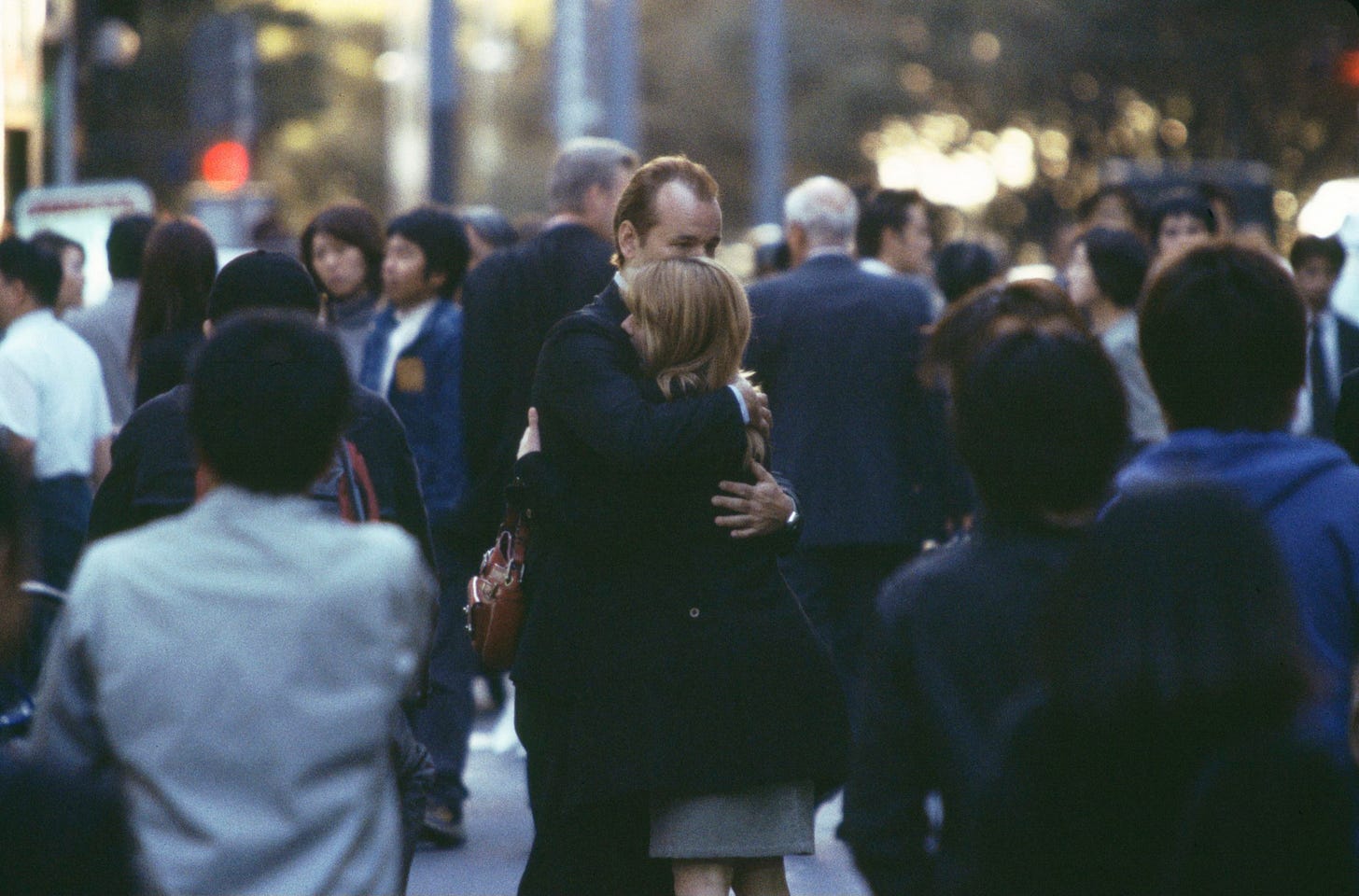

The writer-director’s second feature is a feat of levitation, contemplation, mood and love, love, love, a playful, romantic meeting of two lonely souls of different generations (Scarlett Johansson, Bill Murray), lost in Tokyo, deprived of indifferent mates, adrift in an empire of signs without meaning, only recognizing a fellow forlorn face across the bar in the Tokyo Park Hyatt, across a generation or three. There's vernacular grace in the pair’s wanderings across the gaudy topography of Tokyo Coppola finds, reminiscent of Wim Wenders’ work, in which a scene could take place only in a particular room or street, or against a particular dazzling yet puzzling urban backdrop. Lost in Translation has the dreamy pace of memory as well, as if only the most heightened sensations are recalled and the boring bits fall away.

For many, Lost in Translation defined the Sudafed-and-Johnny Walker mind-set of 21st-century road warriors—jet lag as Ecstasy; regret, longing and displaced desire as woozy narcotic. Murray plays a fiftyish actor whose career and marriage are in decline being paid $2 million to perform in a whisky ad; Johansson is the tagalong wife of a photographer on a shoot (who likely neglects her even at home). Adrift in Tokyo’s Park Hyatt, with views of the city starkly evoking Blade Runner, the pair meet. And meet again. It’s not a May-November romance, but something more elusive, more transitory. “Their relationship was more like a friendship. I didn’t want it to be a typical kind of cliché,” she tells me as we sit in the second floor restaurant of the Chicago Park Hyatt, overlooking Chicago’s 1869 landmark Water Tower.

Lost in Transltion has quiet authority, much like Coppola in person. The thirty-two-year-old writer-director is tiny, incredibly soft-spoken and resistant to describing her work. Yet she has a presence you want to trust implicitly. She describes the movie’s genesis rising from trips she took to Tokyo, first as a tourist, and then promoting her Milk Fed clothing line (sold primarily in Japan). In terms of style, she says, “The starting point was the impressions of being there, the blurry neon. The [continual weave of] music helps, that kind of dreamy… it’s like you’re on another planet. And I wanted something that I thought was romantic, not something that was supposed to be romantic. Like, a lot of movies are supposed to be romantic are kind of corny.”

“Being at that point, in your early twenties,” Coppola says you ask yourself, “What am I going to do with my life, what kind of person are you going to be? That confusion is amplified by jetlag in this really foreign culture. Your visual impressions in a half-awake state are just not the same as your reality.”

The movie is similarly jet-laggy. “We were never precise about what day we were on. It’s like when you’re on a trip or you look back on a week in your life where all this stuff happens, it’s blur. Was it three or four days? I wanted to be impressionistic.”

The image-rich pace of editing reflects that choice. “I don’t think it’s a conscious thing. It’s an idea about fleeting movements, moments that can be enchanting or beautiful but part of what makes them great is they don’t last.” There are shots that are technically “incorrect,” but are lovely in their own right, such as a scene both hilarious and touching, when Murray does karaoke to several songs, including Roxy Music’s “More Than This.”

“You mean when they’re doing karaoke? It’s sloppy? Yeah, there are other shots, like at the end, where she’s out of focus, and that’s the nature of how we were shooting. [That section] was all kind of improvised, done documentary-style. Sort of a homemade quality to it. So it wasn’t intentional, but I was inviting it to be a little homemade or sloppy, it was more about the feeling. Instead of losing a moment by being precise, I wanted to capture what was going on.”

Music is a mood, almost incessant, such blasting from each storefront they pass, yet blending with the one before and the one to come. A passage from My Bloody Valentine is used once, for a driving scene. Coppola uses it for mood. “Kevin [Shields] wrote new music, but that was an old My Bloody Valentine song I wanted to use. I just loved the feeling, they’re into each other, they’re driving home and that captures that feeling. I like that moment, blurry neon, the music, feeling.”

Do they get intelligently lost? “Maybe! I dunno, maybe they’re just lost. I feel that way when I go there. I know a few people, but it’s still really confusing to even go on the subway, it’s an adventure.” (There’s a shot on the subway that cuts away at the split-second it registers, stolen on the subway, of Johansson’s hair momentarily aloft, caught by a breeze from an escalator.)

The film opens with a dreamy shot, a horizontal frame of Johansson’s lower back, in translucent panties pink like cherry blossoms. It almost seems a provocation as well, like “Hey, look, I’m not a guy directing this, I can do this”—

“And you can’t?” she finishes the sentence, laughing. “I never thought of it like that. I just wanted to have a moment, a flash of her femininity before you get into his story, to hint at her. I saw the paintings of John Casares, photorealism of all these butts in underwear and when I saw his book—my brother [Roman Coppola] is into him—I said, that would look good as a title sequence. And I always liked the Lolita title sequence, just her foot. [So it’s] abstract and iconic and feminine. And later you see her hanging out in the pink underwear. It’s just supposed to be an impression of her, if [the film] is all memories. I thought it would just cut nicely—to see pink underwear and then neon. These movies are collages. I didn’t really have an intellectual reason. You just do what you like and not think about it too much.”