THE NEED TO TOUCH WITHOUT BEING TOUCHED.

To act with the imperviousness of a violent, inflexible law of physics. To speak voluminously, incessantly, yet be heard only by oneself. That's Johnny's loneliness. Mike Leigh's brave, brilliant Naked is a corrosive masterpiece, as likely to alienate as impress. Leigh describes his film as a "lamentation" about male aggression. His male characters, simply put, hate women as an integral part of their own self-loathing. This isn't sexual warfare: it's apocalypse. His protagonist, Johnny, obsessed with how the hardly evolved "cheeky monkeys" got to this end of the evolutionary scale, is presented as more Man than man: this is the premillennial condition the English condition is in.

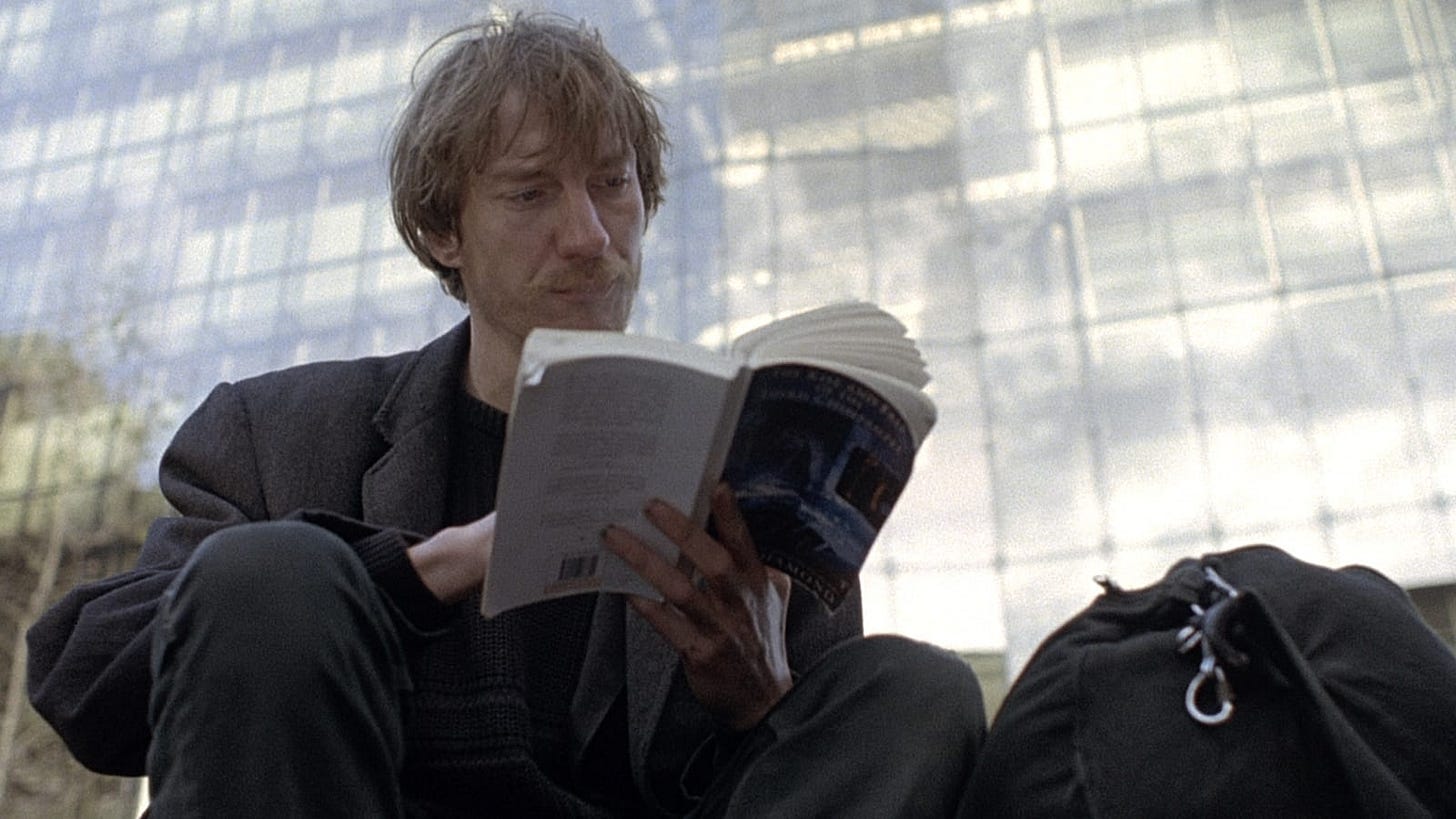

Naked's core is David Thewlis's commanding, ceaselessly articulate vagabond: 27, from Manchester, a barmaid's son with a silver tongue, constant headaches, and some dangerous knowledge of psychology. Lean and shaggy, with large, sad eyes, Johnny is a hyper pup with a gift for talk. And what talk—the acrid fumes of a soul spending itself. Johnny has the fearful potential of insight. He murders with his mouth; he seeks compassion in order to tease it out and slay it. How dare you love me? If only for a few hours, his magnetism transfixes everyone in his path: ex-girlfriend Louise, whom he travels to London to see; her mumbling roommate who falls madly for his wit and rough sex; a philosophical night watchman; and a hilarious, if sad young Scots couple, whose near-incomprehensible grunts and yelps seem torn from the lower rung of Johnny's beloved evolutionary scale.

Leigh's extensive television work and movies like High Hopes (1988) and Life is Sweet (1990) trade in serial social embarrassments, epic awkwardness, and sometimes hilarious caricature. (And of course, after Naked, we have Secrets and Lies and Topsy-Turvy, refined and filigreed editions from the same cool eye.) But Naked bursts through the finely observed domesticity of the earlier work, making a leap into darkness. Leigh makes his movies with improvisation taken to seemingly mad extremes. Starting with little more than a notion, the director and his actors discuss possible threads of story and character for weeks, then partially base their roles on an acquaintance. In Naked, another familiar Leigh device rears its woolly head. If a central character has a bad habit, Leigh often sets up another character who's much worse. Johnny's doppelgänger in male aggression is a vile, arrogant landlord. With his Porsche and hundred-pound-notes and Dirk Bogarde looks with dead black devil's eyes, he'd fit comfortably alongside Ted Bundy.

But placed next to Johnny, that character is pure laziness. Johnny is a magnificent black cloud, an angry young Antichrist who puts the pissy antiheroes of late 50s and early 60s English theater to shame. Johnny plunders the depths of hellishness for good material, a Stygian stand-up who's his own worst audience. Like Johnny, everyone in Leigh's London is adrift. The nuclear family has detonated, leaving a dank wasteland whose citizens live with the most tenuous connections to ideas of comfort and home. The dead capital of the ancient empire is all mildew, damp and verdigris, with a perpetual overcast to chill the bones. In Leigh's construct, Johnny is at the highest stage of evolution and the highest circle of hell. With dozens of references to "the missing link," “The Odyssey,” and prophetic writings in the Bible and from Nostradamus, Leigh and Johnny are never not conscious of the multiple meanings of his traipse through London along what Johnny laughingly calls "the via Doloroso." Still, this prophet without portfolio, drawing from his cracked gospels, is not just another suffering Christ waiting to be nailed to the cross of that popular symbolism. He's more Dostoevsky on the dole: a fevered creature with too much in his brain, powerless to change the world or shed his skin.

At first rub, the many metaphors and allusions chafe, but Thewlis and Leigh are more than up to the task, carrying off their conceits with impressive bravura. For instance, Johnny's ideas about the emptiness of the modern soul are made literal when a lonely night-watchman lets him into the "postmodern gas chamber” that he's paid to watch, with floor after unoccupied floor of empty space. The ten-minute sequence of almost-unbroken talk is exhilarating and exhausting. Like the watchman, we're unwitting pupils to Johnny's too-clever-by-half Socratic dialogues.

Leigh's television-bred style at last seems eminently cinematic, his seeming visual restraint demonstrating itself again and again as sly, patient pattern-making. Leigh is aided immeasurably by Dick Pope's lighting schemes, working from patterns of darkness into pools of light to darkness again. There are three pivotal points where the camera eddies around a becalmed Johnny who seems ready to disintegrate. At these rare moments when both his mouth and feet are still, Leigh's camera swirls around him with a vertigo so profound, you can sense the neuralgia bursting from Thewlis' brow. And at moments like these, Andrew Dickson's forceful score for harp, viola, and double bass, is as lyrical and wounded as Johnny's language.

To the bewildered young Scot bellowing for his girl, Thewlis' Johnny has an instant that startles even on the third viewing. Watch Thewlis' face: after taunting the other man for a few moments, there's a quicksilver change from antagonism to laser-like insight, as he suddenly, flatly, asks: "What's it like being you?" It's the question Johnny keeps asking himself, staring into an abyss that responds with deathly silence, but a silence more comforting than mere concern.