Steven Spielberg and Minority Report: A Pro's Vision

Steven Spielberg and Tom Cruise traveled to promote Minority Report in advance of its June 2002 release, and I spoke to them at the Four Seasons in Chicago. As the Apple Vision Pro wends its way into the world, or at least inspires a mess of memes, it’s striking how most of the futurist notions in Spielberg’s sci-noir remain prescient. (There’s a reason for that, which he talks about.)

An edited version of this exchange was published in the UK and Poland at the time. A now-defunct British monthly maintained complete integrity with the quotes, but interpolated a narrative that Spielberg, Cruise and I had spoken in a fancy restaurant and got into a food fight while talking, and that Spielberg made fun of me for having lettuce caught in my teeth. The real-life setting was more banal, in an empty conference room for forty-five minutes.

This is the first publication of the full Q&A.

So many movies! So what is it about Philip K. Dick?

I never met the man in my life!

His writing, then. I know, I know he died before Blade Runner was finished.

I am familiar with his work. But I had not read the short story of Minority Report until Tom sent it to me. When I read it, it was gripping. The premise, what I was attracted to, it wasn't really a story, it was a set-up. I thought it was the set-up for a story, waiting for a story to find it and attach itself to it. It was a brilliant set-up about a future time where crime can be—murders can be stopped before they happen and future perpetrators are put in prison, in complete violation of their civil rights. Gee, I thought, what kind of country would be so desperate and so afraid that they would give up that much of their personal freedom in order to insure their personal safety at night from homicide?

That's the kind of science-fiction you like?

That was the kind of science-fiction, kind of like a film-noir science fiction, that influenced to make this my film noir. I'd never tried a movie like this before. It was a way of telling a story.

And thematically, it has a lot of things going on, including disturbing social themes.

It's sci-fi, it has disturbing social themes that are very relevant today.

This is the first movie I can think of that was named after the MacGuffin.

Yes, The Man Who Knew Too Much was not called "Ambrose Church." [laughs]

What's your favorite Hitchcock movie?

My favorite is North by Northwest in terms of the fact that it was his most commercial adventure film he had made in his life. I couldn't believe he made it. When I first saw it, it didn't even seem like an Alfred Hitchcock picture, except that he's in the first couple of scenes as he is in most of his films. But my favorite Hitchcock film in terms of just sheer brilliance in the craft of storytelling is Strangers on a Train. That's always been my favorite.

How conscious were you of investigating his style of storytelling? There's that great story in the Truffaut-Hitchcock interview book where he thought the ideal scene would be in a car factory, you'd see two people talking and follow a car being assembled, starting with a chassis lowered onto the assembly line, and when you reach the end of the line, open a door a body falls out. You don't quite do that, but there is a scene here that winks at it.

Yeah. Yes, exactly. We had some fun with it, especially for people like you who know the ins and outs of all the minutiae of film. We were playing with that, but also, y'know, the car scene was just another setpiece that I wanted to do, to create a [scene with a] little bit of a surprise ending, but also to show the future, to show how there's no people on the assembly line at all, not even supervisors, the way there is today.

How relevant is this to the U.S. today? It could be taken as Attorney General John Ashcroft's wet dream. Should civil libertarians use it as a jumping off point for debate?

I certainly think that's possible. Civil libertarians could use this as a sort of rallying cry, but at the same time, you have to understand that the dangerous results of losing our personal freedoms, that the end of Minority Report, which we don't want to give away, is all about. So I think John Ashcroft would like the set-up, but he wouldn't like the statement that the film makes at the end. Y'know, that to survive as a human race, we can't rely on the gifts of precognitives to solve our problems for us.

So at a White House screening, you could leave off the last reel?

I very much doubt they'll even ask for this picture at the White House. [laughs] If they do, I'll be happy to send it to them.

So adapting this source material, Dick's short story, is different from how you pulled together the screenplay of A.I.

es, because that was Stanley's story. Stanley had spent twelve, fifteen years working on A.I. I just followed Stanley's writing. I was lucky to have a ninety-page—basically a treatment, written by Ian Watson and Stanley Kubrick, and I had a chance to go through another hundred pages of Stanley's notes, his own personal notes, all in longhand, by the way, not typed up. Very legible, very easy to read his handwriting. And then I had the opportunity to have almost 1,400 storyboards Stanley did with Chris Baker, who worked on A.I., who I hired after Stanley's death. And I had ten years to talk to Stanley about the movie.

So I was really like the kid sitting on the Lakers bench, just saying, if you need me, I'm here. the original Brian Aldiss story was about nine pages, only part one of an episodic of stories he wanted to write about David. That's a whole different story, because that's a story where I really followed the blueprint of someone else. I'd never done that before, y'know, except I've adapted books, of course, but I've never adapted a filmmaker's vision. And I wouldn't have come to the table had Stanley not invited me to tell that story. And then when he died and his family re-invited me, I felt I had to say yes. this was different. I got my freedom back on this one, not having to serve a master who is a master and a man who I had just looked up to all my life.

Film has a responsibility to do everything. To entertain, to illuminate, to teach without being preachy. Film should reflect on events that aren't taught sufficiently in school, which is why I made Schindler's List, which is why I made Saving Private Ryan, why I made Amistad, but at the same time, films should only inspire, in my opinion, students to discover an interest that maybe they'd never had before and then to forget the film that they saw, that just acted as a catalyst for their discovery, and leave that, I hope, in the dust, and then go really read books and understand what World War II was like, what the Holocaust was like.

So how do you flesh out the bones of Minority Report?

Pretty much the short story doesn't go into... It's hard to answer your question, since I have to reveal the plot and the plot surprises in Minority Report, which is hard for me to do. There aren't a lot of surprises in Philip K. Dick's short story, at least as not as many as we put it. In the area of surprises and feints and red herrings and, y'know, we're a little more complicated than the original story. I think he had a great premise and took it as far as he wanted to take it.

Why do you also make films about history? Not that Minority Report is history, yet. It almost seems like you feel it's necessary, that nowadays history isn't compelling to a larger audience unless you make a film of it first.

I know what you're saying. History is taught in this country, [but] I don't think it's taught with purpose and passion, it's taught by mandate. But I also feel that film has a responsibility to do everything. To entertain, to illuminate, to teach without being preachy. Film should reflect on events that aren't taught sufficiently in school, which is why I made Schindler's List, which is why I made Saving Private Ryan, why I made Amistad, but at the same time, films should only inspire, in my opinion, students to discover an interest that maybe they'd never had before and then to forget the film that they saw, that just acted as a catalyst for their discovery, and leave that, I hope, in the dust, and then go really read books and understand what World War II was like, what the Holocaust was like. I'm always happy when people say, "I saw your film and I was not interested in the Holocaust, until Schindler's List, then I began to read, I read Primo Levi, I read Elie Wiesel and all those books..." That's what I like to hear. The good news is they're not talking about my film, they're talking about the books they're reading about it. So if it be a pathway...

I think we're such a communal society that we will insist on always sharing an adventure with strangers in a dark room, no matter what the platform or hardware is, that we will always insist on that. My greatest dream and wish is that we never give this up.

There's intricate, sophisticated social commentary in this movie, and I wonder if the people whose behavior you're critiquing will even see themselves in it. This is a world of even more commercial bombardment than we see today.

When Tom had the cereal box in front of him, we had no graphics on it. It was a blue box, we'd put the graphics on later. He had the blue box in front of him. He said, what does the box do? I say, it's like a jingle, "Eat this cereal," I begin to sing stupid songs to him, and Tom says, you know what I would do if this box starting singing, I'd throw this fucking thing across the room! I said, you would? Let it sing a little bit, tap it a couple of times, then throw it across the room. That's why he does that. It was infuriating, in Tom's imagination, that a breakfast cereal would be talking to him. We're not that far away. We have holographic 3-D imagery on the back of cereal boxes today. We're starting to approach our food talking. Our food started talking to us in 1955 with Snap, Crackle and Pop, when they invented Rice Krispies. Food had a voice in 1955! Once technology allows the imagineers at all these corporate companies, tennis shoe companies, cereal companies, y'know, lingerie companies, anything, you name it, once they have the technology, they're going to use it. It's like the atomic bomb. If you build that atomic bomb, you're going to have to use it. Once they find out how to use it, I'm going to have my comb talking to me in the morning: "You're going against the part! Danger Will Robinson!"

By 2054, who will have won, Lucas or Spielberg? Digital or film?

I will lose and George will win. By 2054, it will all be digital. George will win. It will just be inevitable. But I'm going to have this deep pit somewhere in the middle of Kansas and I'm going have four million feet of Eastman Kodak negative buried there so I can sneak over there and take just what I need to make my movie, shoot my movie on film, y'know, in defiance of the digital era. I think there will be a convergence with video games. By the way, I'm not advocating this. Everything I'm saying to you right now, don't say, "Steven advocates this." I'm saying, I'm just telling you. I don't advocate everything that's in Minority Report. I'm saying that could happen someday. Just because I directed a movie doesn't mean I want it to happen. I'm just saying these are some dangers that may await us around the corner. But I think that the convergence of video games, first-person games, first-person shooter games, or at least games where you are able to navigate in an entirely three-dimensional world and decide where to go and when to go and decide when you want the story to be told to you, be in neutral, hanging around, not having anybody tell you a story.

Eventually, I think, movies, the narrative story which I love to do so much and the story with a viewer, with the audience empowered to just take my story and do it, and tell my story back to them any way they choose, go to the third act first, the first act last, in order they choose that day is coming as well.

Talk about the scene where you show the theater of the future.

I have that scene in the movie. At the end, Anderton [Cruise] goes into the cyber-parlor to download Agatha [Samantha Morton], and in the parlor, my writer, Scott Frank, is sitting in one of those booths and a bunch of cyber-people are telling him what a great guy he is, "You're the man," and he's saying, "No, you're the man, thank you very much," that is what you would call an environmental story where you are literally wrapped up in a body suit, the body suit has pressure points on it, it stimulates you, it touches you, if you're in a fight, you can feel some of the softer punches, and it's kind of like those rides at Disneyland where you're on a simulator and you move in synch with the imagery. This is kind of like a more claustrophobic experience.

So we lose the communal experience.

I hope not. If I could choose, the communal experience would always be with us. And I think we're such a communal society that we will insist on always sharing an adventure with strangers in a dark room, no matter what the platform or hardware is, that we will always insist on that. My greatest dream and wish is that we never give this up. The futurists in our roundtable were talking about stories being told directly into our subconscious and we'll have them fed to us, we'll have a couple of innocuous little sensors on our temples, our temporal lobes, and not unlike Minority Report where the imagery comes out of Agatha and the precogs and onto a screen, imagery will go into our minds and we will actually be in someone else's story, but living a life, someone else's story, a real life for an hour-and-a-half, that is, if we can pass the medical, which must be given to everybody before they go into that experience.

And of course that can be corrupted.

Sure. Propaganda.

Is there something about human nature that makes us turn progress against ourselves?

It's human nature to be part of the event. If you're just sitting at home, passively watching television, you never feel part of the event. But suddenly when the television turns and looks at you and talks to you lying there in bed and calls out your name and says, be part of this, even though it's an invasion of your privacy, people want to be part of a social event and they're going to leap to be the first to stand in line. Look at these reality shows like "Survivor" and "The Bachelor" and all this, I just can't believe that people do this. I don't think they're doing it for a million dollars, they're doing it because they want to win. The money's irrelevant.

Talk about the scenes that are almost totally black-and-white, drained of color. It seems more than just copying film noir's customary black-and-white visual style.

I think the whole movie... I drained Private Ryan of color, sixty percent was drained out, only forty percent held color. I didn't do the same, I used another process here, called the bleach bypass process. It's a laboratory chemical process—you can't do it on digital, it's only chemical! And what it does, it simply takes the Technicolor out of the face, the absolutely red and orange and pink tones out of your face, and the deep browns and gives you more of a pallid, pasty look. the whole film, except for the scene in the swimming pool, the flashback to the swimming pool where we see how [his son] Sean was lost, we didn't treat that at all. The rest of the film? Bleached out.

What specifically encouraged you to start working faster and rougher? Since you started working with Janusz Kaminski, not just with Schindler's List, but even Jurassic II, you've allowed yourself not to be slick, to even be sloppy, as if storyboards never even entered the equation.

I think it was after Hook. Hook really was the slickest movie ever made and the least satisfying, to me, of all of my films, as a filmmaker. It was so conservatively made. I had a chance with that movie to do a breakout new-wave musical and I chose the very safe road. We had eight musical numbers written for it, I threw out all eight numbers, I canceled it being a musical on the second week of shooting. I had already shot one musical number, looked at it, Johnny Williams looked at it, Johnny worked his ass off writing the music for this picture with Leslie Bricusse and we threw the whole score out. Johnny agreed it should be thrown out, he's the one who said, this is not the tempo for a musical, and I made a very conservative movie out of it.

I never had a cup of coffee in my entire life.

I said, y'know, I could make Hook the rest of my life, I could be a director for hire and I can go out and make a lot of movies like this that are entertaining, and my kids love Hook, but play it real safe. Schindler's List had been sitting with me for ten years and when I committed to do Schindler's List, my first promise was to shoot in black-and-white. The second promise was to shoot handheld. My third promise was, be uncompromising in my honesty about the way it really was then. That's what changed my life. The rude awakening with Hook and then the traumatic involvement with Schindler's List, which changed me from inside out forever, just the experience of making that was brutal. I saw that sometimes not having the slickest dolly track, the smoothest crane shots, like John Farrow and C. B. DeMille and all those amazing kind of like glossy painters. Sometimes being rough and honesty reaches people deeper because they see an honesty and reality to the imagery, it feels like it's happening to them. I was able to communicate ideas quicker than in the traditional Hollywood standard and style I had been using for so many years.

But you wouldn't do a Dogme 95 picture.

No, never! Never! I want a really good sound man, I want really good lighting and I want a really good bathroom close by. I don't want to have to go to someone's house and knock on the door and ask to go to the bathroom, which in Dogme, you cannot go to a porta-potty. I want some privacy in my life.

What freedoms does science fiction offer a filmmaker?

Because the rules are different, it's great. Pure science fiction has to be steeped in science before you can mess with the fiction. But, like with Jurassic Park, once I got through the first act with all he science to make you believe that this is how the dinosaurs came into the twentieth century, because of the DNA from mosquitoes and other blood-sucking insects, once I was able to establish a credibility, then I could use my imagination and Michael Crichton's imagination and go to town and be free and liberated.

So the great thing about science fiction is, you start level-headed and honest about the science, then you get to use your imagination, there's no rules, no gravity anymore. that's what's fun. It's like when you ask an actor, what do you like best, improvisation or rote memorization of dialogue. And most actors, if they're worth their weight in anything, will say, I love improvisation. And in a way, sci-fi, for a director, is what improvisation is for an actor.

But that's the gift of any film made in a genre, isn't it? You have these structures and codes already there, you can weave your themes and concerns in a less flagrant way than a social issue picture. Do films that resonate with a larger audience have to embody some deeper mythology?

Yes! Genre is very important. If you can find a genre, like with film noir and the murder procedural, that hasn't been investigated in a while, you're in luck. Except for fans of "Colombo" and "Murder, She Wrote," today's audience has lost the artistry of the genre of murder mystery. The idea for me was not to re-invent the genre, it's been around with us forever, Agatha Christie did it best, but it was just simply to remind people that this is how these stories once were told. I was trying to be as traditional to the genres as I could be, which is why I looked at all of these [noir] pictures and even Chinatown, which is in that genre.

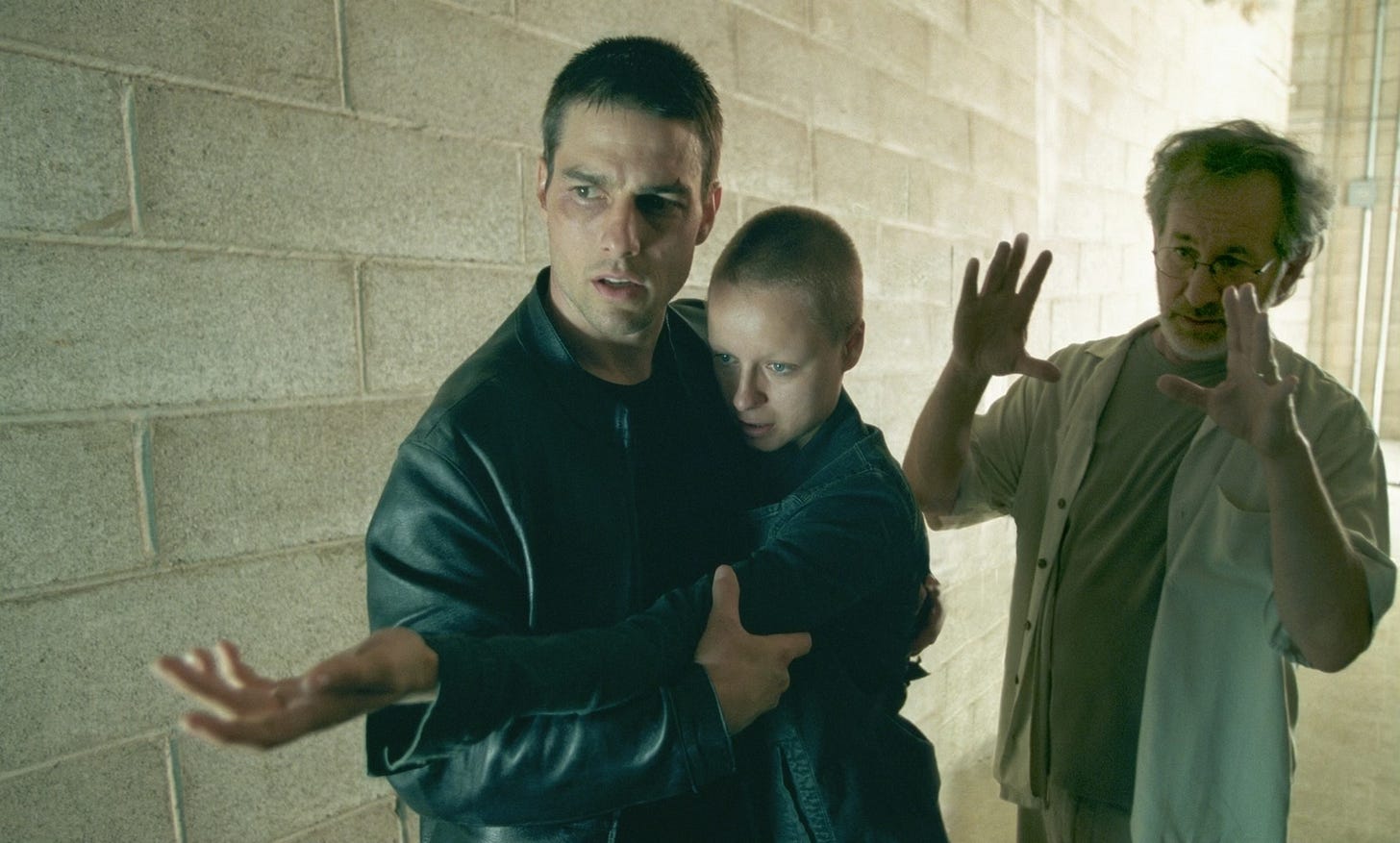

You've wanted to work with Tom Cruise for years.

Together, we're like one personality. We just want to have a lot of fun. We laugh a lot. We cut up a lot. We joked a lot about [a couple of scenes] with snot and eyeballs and tricks we were going to play on the audience. to see how far I could push the envelope. We only disagreed once. Tom said he wanted to do a stunt, and I said, too dangerous, you can't do it. He said, I did it on Mission 2, and I said, but I didn't direct Mission 2 and I wouldn't have let you jump off that, I wouldn't have been John Woo, you wouldn't have been hanging [in mid-air], it would have been a stunt man, not you. Ten percent of them I would not let him do.

He doesn't smile much in Minority Report.

Tom just has to be told to give it up. He never saw this as a big movie-star vehicle, but as a very personal expression of what parents fear most, the loss of a child. that was his first instinct the first day of shooting, and everything about his character was re-informed by the fact his son was missing and he might never be found. It gave him a center of grief, but it also gave a character to play. I think I only let Tom smile two or three times in this movie. I told Tom, I'm not going to let you smile in this picture, hardly at all. This movie is not going to be about smiling, it's going about communicating your intensity and your passion. Tom will do anything you want him to do, but he brings so many good ideas to the set. He is one of the most facile actors I've ever worked with.

Tom's known for getting to know the crew.

On this film, he brought on a guy with a cappuccino stand, kept the crew alert and jumping on caffeine. The crew was so caffeinated by the end of that movie, I could have gotten three more movies out of the same crew, without taking any Saturdays or holidays off. I don't drink coffee. I never had a cup of coffee in my entire life. That's something you probably don't know about me. I've never had a cup of coffee, ever, ever. I hated the taste when I was a kid. It's rare, by the way.

What are you good and bad at in real life?

I thought making movies was real life! When I'm not working on film, you mean? I'm really good at organizing a morning. I'm a great morning person, organizing all the kids, getting their lunches packed and getting them off to school. In that sense, I'm Mr. Mom from about 6:30am to my last, I do three car pools in the morning. So from like 630 to nine, I'm Mr. Mom. But my wife is the real mom for the rest of the day and the rest of the evening. What am I bad at? Probably figuring out consequences for my kids if they do something wrong. Y'know, I'm really bad at that. Not that I'm really tough enough. I'm just always short of ideas. My wife is always much better in the creative consequence department. I think I'm a better dad than filmmaker. The choices I make will affect them the rest of their lives. The choices I make as a filmmaker are choices that, y'know, won't have as profound an impact on the people who see my pictures. So I just feel that fathering and filmmaking are two different worlds entirely. I had a good upbringing, as much as I've complained about it in the press over the years. I look back on it, and I had a great upbringing.

Were the brand names commercial placement? Some parts of this future seems to be little more than glowing advertisements floating in space.

Every brand name you see in the movie paid a fee, some larger than others. I guess the largest fee was Lexus, since Lexus is in more. And I have one!

How about the next Indiana Jones?

That's a ways away. We're not shooting until 2004, it's not coming out until 2005.

Why'd it take so long?

I didn't like some of the ideas, I didn't like some of the concepts. Finally, a concept happened that I like and that Harrison liked as well. George tells the stories, he conceives the stories, then I help write the setpieces with whoever the writer is. But George is the one who crystallizes, this is what this adventure is about. George was spinning off a lot of ideas. He's kind of like a pitcher, I'm a catcher. But I can shake off a pitch, right? I can shake my head and say, let's try something else. George came up with a pitch that Harrison and I thought was brilliant. We hired Frank Darabont a couple days ago to write the screenplay. Harrison's a real young guy at heart and he can still run and fight and keep up with the young guys.

In terms of screenwriting, when do you know it's right?

I never know that it's right! On anything I've ever done. I'm sometimes told it's right, I'm sometimes told it's not right, but in my heart, y'know, I never really know. I know when it's time to stop and let go. But I don't really when it's right. It might be years later I'll look back at something with a lot of perspective, like a decade later, and I'll say, wow, I'm proud of that. I couldn't have done a better job if I had spent another year on that. Other times? I'll see something a decade removed and I'll say, y'know, if I were five years older and had two more months, I could have made a much better picture.

How long was this in development?

Two, two-and-a-half years. The major thing is story, just getting all the storylines. I never realized that when you tell a mystery story, you put a lot of balls in motion, you have to keep them spinning for a long time. There was more work on the script than I've done in many, many years. In terms of production, there was another year just spent conceptualizing the film. In order to do that, I put together a think tank of, we call them futurists, who came to a hotel in L.A., to Shutters in Santa Monica, on our ticket, for a stipend. It was just one of the most exciting— I wish there was a "Nightline" episode devoted to those three days I got to listen to tapes of. We had tape recorders going, and for three days, we talked, what will fifty years in the future be like? I didn't want to know two hundred years, I wanted to know what's the foreseeable future, what's the environment, transportation going to be like? What's medicine going to be like? What will the communication tools be, what will the computers look like? It was an amazing three days. It was a very positive future. If we don't blow ourselves up or somebody else doesn't blow us up, my children can live to be 150 years old, my youngest kids can and probably will. I'm most concerned about Pakistan and India right now. Even in a limited nuclear exchange, they could lose seventeen, eighteen million people within a couple of weeks.

Who came up with the police baton that has the nasty effects?

I think it was Douglas Coupland who came up with the Six Stick. He knew some of the defensive weapons being developed by the he military. One of them, in fact, is a prod, like a cattle prod, that will throw your inner ear out of whack and make you vomit. So that's only about three or four years away.

What did you miss not getting to put in the film?

Well, there was the smart toilet that analyzes what you should be eating and how to live to be 150. I didn't quite know how, I don't remember which of the futurists came up with it, but we all laughed about it and thought it was funny. It was a consensus that is was going to happen... but not in this picture!

So you wanted a texture that felt like how our world is evolving. We get a sense of things of come.

It's about accuracy, especially... I mean, in A.I., the future is unspecified. It's so far in the future, it's unspecified. But this was a specific future of fifty-two years from now, which means it couldn't be, it couldn't be magic, it couldn't seem like magic. It had to seem like there was a technical basis from some of the tools we put in the movie to help the precogs help the Pre-Cops. So that it would not be science fiction, but science that's just around the corner.

Does September 11 change the movies that are around the corner?

Well, y'know, there's a lot of movies... I don't think 9/11 is going to determine any of the movies any of us put out. 9/11 affects how we live and how we think about our futures. But the movies will always be a reflection of our imaginations and our dreams and fantasies and our worst-case scenario dreams and our nightmares, too. But 9/11 should never be a, should never stop us from doing what we want to do in our hearts. I think there's a line to be drawn. For instance, I would never make a movie about 9/11. I would never tell the story of 9/11. I think that story was told brilliantly in the media, more brilliantly than any filmmaker can ever tell it. So I do draw a line at certain things that could exploit the circumstances and the tremendous psychological and physical blow that we received on that. But I don't think it should stop us from telling the stories that we want to tell.

What's left for you to do as a filmmaker?

I am actively, actively, looking for a musical right now. The good thing about musicals, you know how long the film's going to be, the playback gives you a finite number of minutes for each number. I've wanted to do one for years. I've come close a couple of times. 1941 I almost made a musical. That would have been a good thing.