Terry Gilliam Shot Through A Metal Tube

Two long-ago encounters with Terry Gilliam: in snowy Chicago (1995) and sultry Marrakech (2011)

SNOW FLOCKS THE ROTTEN GRAY SKY.

Every airline's flights have been canceled or rearranged, and Terry Gilliam, urgently required in a distant city this evening, once again feels dislocated. We'll have to talk in his car to O'Hare. Gilliam, armed with his violently infectious giggle, seizes on the stretch limo as a metaphor for time travel's meaning in 12 Monkeys, his marvelously rich, complex new movie,.

The fifty-five-year-old Gilliam is as manic as a child. "We've got a premiere tonight in L.A. This weekend in New York, I did over seventy-five interviews. It's bizarre. Technology just makes us more confused, since it opens up so many more doors."

The car reminds Gilliam of how Cole, Bruce Willis' time traveler, is shunted from the desolate future, where a virus has killed ninety-nine percent of mankind, to 1996 where he searches for a renegade animal rights group that calls itself "The Army of the 12 Monkeys." "We get in the chrysalis, then we get in the steel tube! Which is the point! That world is all around us, but why don't people recognize it?"

The script, written by David and Janet Peoples (David wrote Unforgiven and co-wrote Blade Runner), is inspired by Chris Marker's melancholy 1964 science fiction short, La Jetée, and draws its central imagery from it. Like Gilliam's other films, the world of 12 Monkeys is both retro and futurist, a documentary of the universe of found objects clattering in Gilliam's sensibility. There's a lovely interlude using clips from Hitchcock's Vertigo, with Cole astutely observing to sympathetic psychologist Kathryn Reilly (Madeleine Stowe) how strange it is that "movies stay the same, but you change." I bring up the Southern aphorism about never being able to step in the same river twice, and Gilliam nods. "Yeah. It's like being asked to compare my work with Python to what I do now. I suppose there's still a certain sur—surreality— well, surrealness about it, using the same kind of juxtapositions, of scale, time, space. I think the foot at the beginning shows the same kind of fatalism. Whatever you do, there's something you're not going to escape from." He pauses, then mutters, "It seems a very long time ago that guy did those animations."

Cole's a convict whose reprieve will come only if he allows himself to be flung back and forth in time. He eventually agrees with those who think he's mad, and decides it's best to stay in 1996 with Kathryn. Again, Gilliam works the parallels to his life. "After 'Fisher King,' I was spending a lot of time back and forth between the States and London. I have a lot of memories of New York and other places, and I go back to them, it's almost as if the intervening years had never happened. Just at the moment I think I'm one person and I have this life worked out! I used to go on holiday, Morocco, Greece, anywhere, and throw myself into those worlds. Then I'd come home and there was this awful feeling as I walked up the stairs to my apartment, that the apartment just started, with each step, clunk, another bit of the apartment, clonk, another piece blotted a bit of Morocco. by the time I had opened that door, Greece or Morocco had vanished forever and the apartment had taken me over again. It's always been like that, and it drives me crazy."

Taken for being crazy, Cole is incarcerated in a mental hospital, where he meets Stowe and Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt), a loony rich kid escaped from a Tex Avery cartoon. Pitt's astonishing, practically bouncing off the walls in all his scenes. "I met Brad and I really like him, his earnestness and determination. Then as soon as I did that, I realized we had made a huge mistake and we were doomed! But months later, Brad worked his ass off and it shows. He's fantastic. We were the beneficiaries of being on the rebound of him being the sexiest man in American, which he hates. All those twitches and mannerisms? He really worked for it."

Gilliam also admires Willis' work. "I've seen the film, what, fifty or sixty times? The more I watch, the more impressed I am with Bruce. He's so understated. There's a lot of people who don't like Bruce because of all the macho, smart-ass films he does. My big fear was that I thought people who would really like this film won't go because it's got Bruce and Brad in it, they'll think it's that kind of film. And the people who go to see Bruce and Brad will be disappointed because it's this kind of film. I'm dying for it to open and see what the reality is!" Gilliam giggles, then resumes his earlier train of thought. "We're just surrounded by this stuff. Of all this information that surrounds us, what bits are important, what applies to me, which can I ignore? And nobody's really certain, so you're kind of nervous the whole time. That key bit, the answer, the meaning of life might have—fweep!—gone by when you weren't looking. I think instead of informing us it's turned us into even more neurotic people. Mobile phones! In the past, when you rented a car, you couldn't contact the known world from that car. So what you wind up doing, of course, is calling friends, whatever, then the phone conversation is constantly interrupted by bad connections or you're under a bridge. So then you become more neurotic wondering what you lost in the conversation. Before, driving a car was just one of the great things, you were free."

On the median, an O'Hare-bound train thunders past. I mention how Gilliam's use of contemporary, rundown Philadelphia locations is reminiscent of Godard's Alphaville. "Christ! Alphaville is so simple," Gilliam says. "But Godard caught an atmosphere with no money. I admire that film tremendously. I wish I could be that restrained and restricted." But 12 Monkeys is a more complex film. "Not that you would know it from the questions I get. 'Is it a hopeful ending, Terry?' I get asked. What I think it is, is a transcendent ending, it's very beautiful. I get teary, it just gets me, there's something very beautiful that happens there. Oh it's a downer, oh it's a happy ending, that's the choice? That's how films have to end, it's binary, it's on or off? That's nonsense. That's the vocabulary you have to deal with in most stages of filmmaking, from studios to critics and interviews. It's so limited. I've got this whole world [we've constructed] to deal with and it's down to this? There are interviews where you talk about Brad and Bruce's butt. After all that effort, that's what we talk about?"

I joke, "Ambiguity—is it good or evil?"

"Each one of us who makes movies has some kind of impact. Isn't that what It's A Wonderful Life is about?" Gilliam giggles. "There's something about the human spirit that seems so irrepressible no matter what you throw at it, that always astounds me, so in that sense, yeah, it's there. An awful lot of the time I get very depressed, but it doesn't matter. Life's a pretty good ride to go on, however bad or silly it gets," he says as the long car pulls up to the curb.

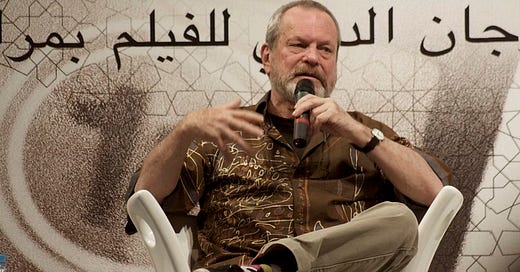

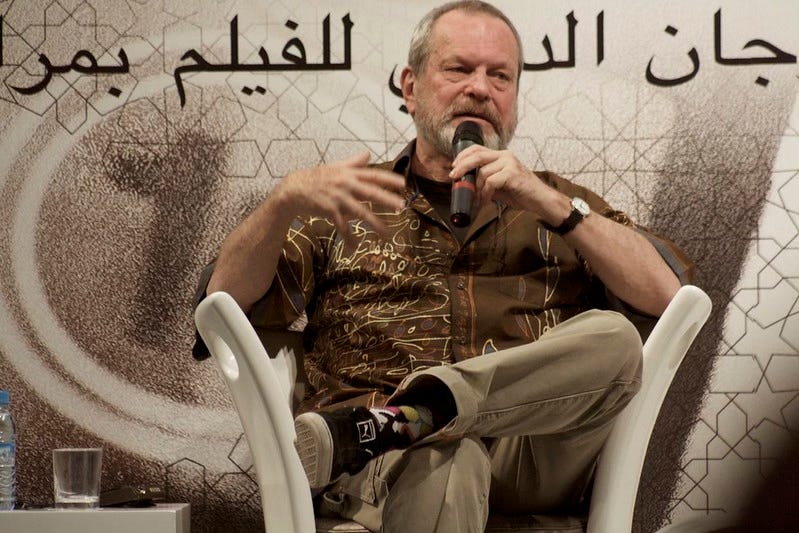

Smack in the middle of the nine days of the tribute-laden eleventh edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival in early December [2011], three sentences kept popping up among English-speaking journalists: “We’re in Africa“; “That’s a lot of food” and “Where’s Terry?” As in… Terry Gilliam. (Insert characteristic giggle.)

A packed late-afternoon masterclass of largely young faces sang with Gilliam’s familiar fast, funny, unguarded commentary. The simple question, “Why film?” got a simple anwer. “I suppose it’s the best job out there.” He laughed, often. “I get rid of all my nightmares by giving them to you.” When things go wrong, he’s inspired: “With no choice, you have to just be instinctive… I’m lucky that way, things aways go wrong.” Gilliam sounded one of his familiar refrains: “The trick is not to have a career. If you don’t have a career, you don’t worry.” Catering to others’ expectations is trouble, he said. “The worrying thing is who is the common denominator—” he trailed off for a second— “It’s not my fault!”

Gilliam on not-the-last Don Quixote disaster and what any potential filmmaker should take from it: What I love about Don Quixote is that he keeps misinterpreting the world. He thinks the world is either worse or better or whatever. He gets it wrong every time. He has these heroic, epic moments and he seems to be unstoppable. He just goes on and on and on. I think he’s a great example for people, especially in film, in how to get through life, because films can often be incredibly disappointing. What I like about the documentary is that so many other filmmakers, when they saw that, they could start telling me their stories of equally horrible disasters. It’s a very difficult business. That’s why I like the documentary, it should discourage anybody who’s not willing to live in a world that disasters like that occur. Don’t make films if you’re not going to be able to deal with things like that.”

On the night of his honor, Gilliam is introduced by jury president Emir Kusturica, who explains Gilliam and his genius in terms of his relationship to Kusturica and Kusturica’s genius. Gilliam doesn’t care: the consistent, grateful giggle’s there in any case as he accepts his Golden Star Award. The 1970s game show trappings suit Gilliam’s apparition…

… as if he’s teleported onto the east coast of Africa into a music hall revue from some doomed film set elsewhere, on the other side of the planet.

And at the fall of the next night, just past 6pm…

Gilliam, a small bright angel, poses for photographers on the stage with tens of thousands of viewers estimated in Djemaa el Fna behind him before a screening of The Imaginarium Of Dr. Parnassus.

Projecting The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus to a crowd of thousands in Jamaa al-Fnaa square in front of the night market. The expanse is a great place to buy fresh-squeezed orange juice, buy fantastic street food for nothing at all, see bits of a movie with thousands of others, and just maybe get run down by a dirt bike in a teeming, suitably Gilliamesque tapestry.

You just reminded me, over the holidays in December 2019, I was on a tour of Jewish Morocco, one day as we travelled from Marakech, we watched Casablanca on the bus. Now that would have fit into a Gilliam movie.