Time is James Cameron’s great hiccup.

His worlds warp the future with the past, and several movies he’s made, such as Terminator 2 and True Lies, have stood against breathless hurry to meet studio release dates. Pre-release buzz on the multi-hundred-million-budgeted-and-more Titanic dwelt on the cash invested by a pair of media conglomerates.

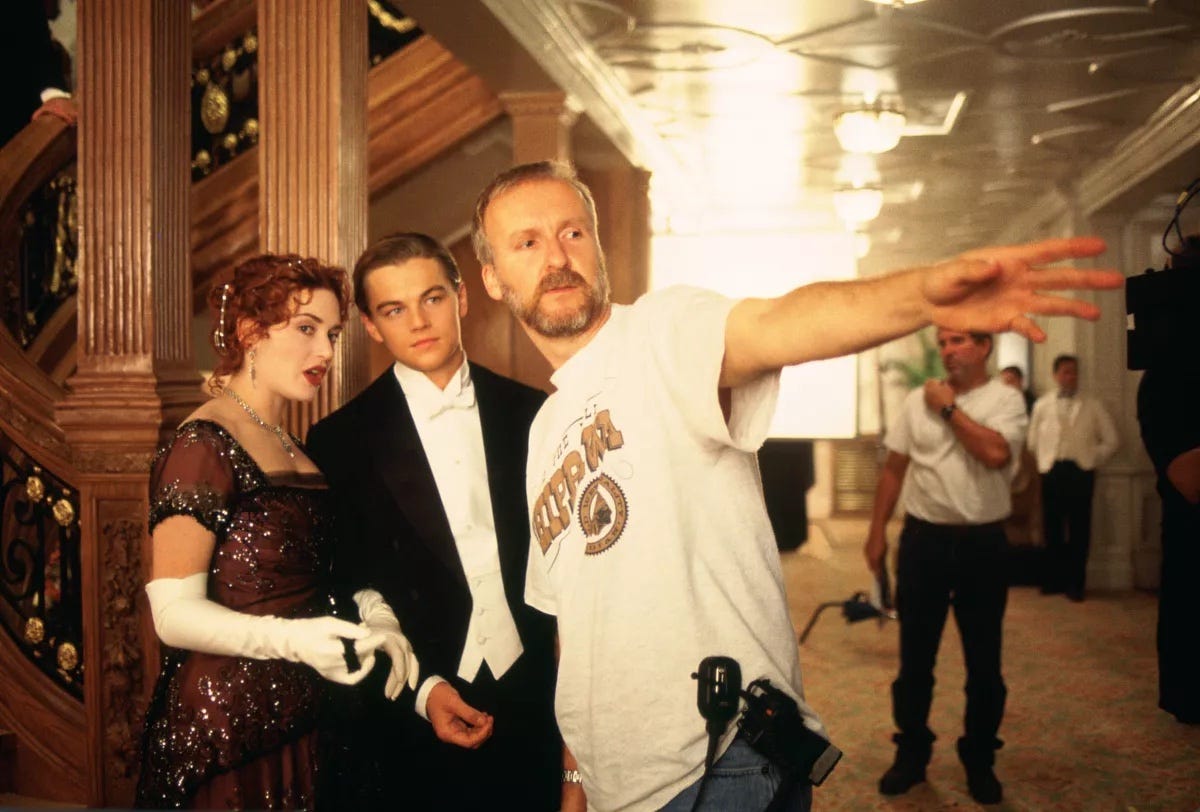

But now that Titanic is on the horizon, you can see what’s up on the screen. While as a driven storyteller, Cameron not only tries to raise the level of commercial moviemaking standards, he also erects dauntingly colossal challenges to himself as a filmmaker. And as with the Terminator movies, time and memory remain his fixation. Cameron dares to combine his knack for spectacle with the intimate details of a sweetly corny, silent-era-simple love story between the privileged, but trapped young socialite, Rose (Kate Winslet) and the dead-broke but still-spirited artist Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio). Then he provides a contemporary set of bookends, unfolding the story through a 101-year-old survivor’s recounting the story to a crew of techno-buccaneers who intend to salvage valuables from the long-dead wreck. While Cameron’s dialogue never rises to literature, his storytelling verve, in details large and small, again demonstrates his grand range of skills.

The obvious opener for Cameron was to ask his definition of a great love story. “A great love story, to use your term, has to be somehow memorable,” the low-key yet intense writer-director says. “The special ingredient that makes something great is a novelistic sense of completion of the character, not just of a moment, but a real understanding of the two characters. In the case of my characters, there is a historical reflection on Rose’s life and the effect that love has on it. It’s not enough to feel the passion of the moment. You could say a good love story was Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. Standard characters, you like them, you like seeing them fall in love. But there’s another dimension, in, say, Dr. Zhivago when he sees his great love and can’t reach her and he lets go so she can survive. Scenes like that stay with you. A great love not only is cathartic, but it’s a catalyst, like for Rose, to become a better person.”

It was never a question of arrogant confidence. It was never like, throw enough money up on that screen, then fuck ’em all. We’ll grind ’em under our wheels!

One of the more thrilling aspects of Titanic is its deft balance of intense intimacy and immense spectacle. “It’s funny, I’m winding up the cycle of question-and-answers about the film and no one poses the question in those terms,” Cameron says. “They ask, what was the greatest challenge of making this movie, assuming it’s sinking a ship. The real question is how to create a sense of intimacy and have that, for the audience, on an eye-level with the big setpieces. I’ve tried to embrace those extremes in everything I’ve done. But you get better as you apply what you learn. You find what’s intrusive. It takes a lot of experience before you no longer feel compelled to show off as a director, instead of letting the dramatic goal of the scene dictate the style.”

Cameron says that the contrast in scale of scenes was sometimes comic. “Certainly, the hardest experience of my career was going from a cost-report meeting where we realize that this thing was costing tens of millions of dollars more than it was meant to. I’m thinking, ‘Man, this is a real high-wire act, we’re really setting ourselves up for a fall here.’ I’ve had enough experience with the media to know what would happen. Then I go up to the set and do a scene where four ladies with big hats and corsets are taking tea. Talking about the printer botching wedding invitations! ‘I’m doomed,’ I thought, ‘I’m just doomed!’ I felt like Captain Smith after he hit the iceberg; it was only a matter of time.”

There is a magical shot of Titanic being towed out to sea, the immense ship filling the view of a golden horizon and flanked by a throng of tiny tugs, depicted in a glassy way that suggests postcards of the period or a pre-digital era of matte painting. “It’s funny,” Cameron says “When we were putting that scene together, I was debating taking it out because the effects looked a little bit like moving paintings as opposed to a one-hundred-percent lucid sense that you were there. At a certain point, I thought, y’know, maybe that’s not such a bad thing. Maybe it’s just that any image that’s very slow-moving, uses enormous amounts of people and that we associate more with black-and-white photography than with color, it’s going to look that way.”

DiCaprio’s character is looked upon as an amusing arriviste when he dares mingle with First Class. There’s much in Dawson that resembles how the press has portrayed Cameron over the years, as though he were some sort of barbarian bounder, this Canadian-born once-upon-a-time truck driver. Cameron laughs heartily. “Right, right, yeah! There are elements of me in every character I write, but I think more so in Jack, because I do come from blue-collar origins and have always tried to approach making movies without pretension. There’s a part of me that’s still the 19-year-old artist who’d sit in the quad at college drawing people’s faces with no sense of the larger world. I entered this world not because I wanted to be involved with the system in itself. Hollywood with its premieres and all that, It always feels slightly alien to me. None of that is necessary to the act of creation. I think part of what people really don’t understand about being on one of my sets is that I’m applying a blue-collar work ethic to what is perceived as a gilded life.”

In Titanic, the shipbuilders boast that they’ve built the “largest moving object ever made by the hands of man.” Now Titanic is one of Hollywood’s largest moving pictures ever, and no one knows yet if it’ll float. Cameron laughs. “Yeah, there are interesting parallels. Arguably, this is one of the biggest films in history, certainly in unadjusted dollars, and we knew this going in. But it was never a question of arrogant confidence. It was never like, throw enough money up on that screen, then fuck ’em all. We’ll grind ’em under our wheels! I don’t think we would have spent all the time on the chemistry between Kate and Leo’s characters if that was the case. We would have relied on pure spectacle.”

—Published in a slightly different version, Newcity, December 18, 1997