CAMERON CROWE TOURED AMERICA for Almost Famous before its release twenty-five years ago. It opened September 30, 2000. We spoke on a high floor of a hotel in Chicago, curtains blowing in open French doors. Kate Hudson was nearby, wandering barefoot on plush carpet. This is a lightly edited version of that conversation.

The White Album

The words and sentiments in the best pop movies are singular and salutary, and knowing that, makers of movie dialogue often reduce heart and hope to trailer-ready phrases.

Writer-director Cameron Crowe has at least one infernal phrase to his credit: “Show me the money!,” anyone? Yet the nerve and fortitude of his characters' struggle to be good and kind and, well, happy, lets me disremember that fancy of the zeitgeist.

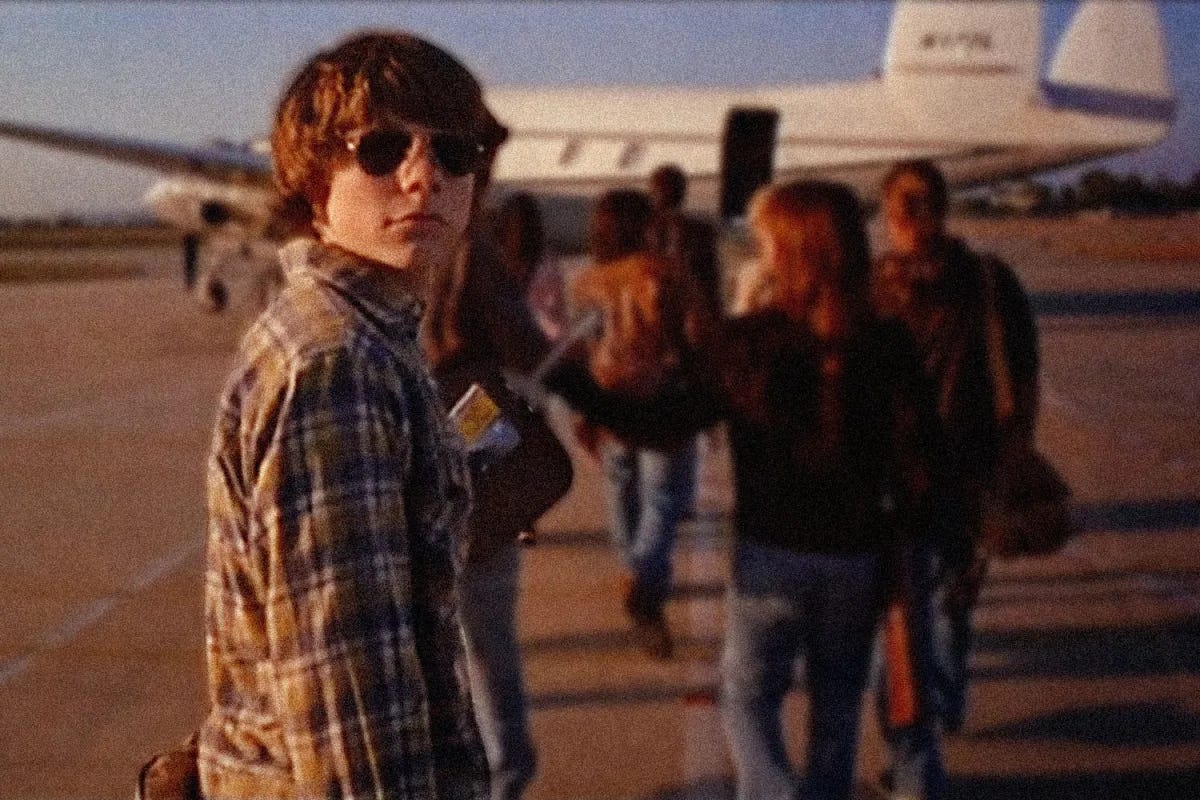

Almost Famous, Crowe's fourth feature, is a flighty fairytale of his own youth, spent as a journalist barnstorming the 1970s U S of A as a precocious, underage reporter for pre-zine rock magazines Creem and Rolling Stone. It's tempered autobiography, drawing on his experience touring with bands like Led Zeppelin (who, in a rare posture, allow five of their songs to be used) and wrote, among other notable Rolling Stone pieces, an unwavering, confessional profile of Jackson Browne, which left that then-faded icon feeling burned and betrayed. His stand-in is one William Miller, played by observant newcomer Patrick Fugit as a boy too young, too sweet-faced, to have any hair to stand up on the back of any part of his body. He has discovered escape, from the confines of the home of his complex, controlling mother (played with delicious specificity by Frances McDormand), and from the confines of his mind by rock 'n' roll. Now there is the making of the music: the bands, the battles, and yes, the girls who pave the path with golden smiles.

Crowe may be the lyric bard of happiness in big-scale American movies: a filmmaker who is a maverick simply because he's seeking bliss and joy in stories of puppiest love and mooniest longing, rather than through the invocation of head-rush modern technology (see under: The Matrix; Run Lola Run; Fight Club.) I can't resist what Crowe's trying to do: it's almost impossible to write well about bliss. Longing, yes, regret, yes. Ugly souls and bad men are joyful to describe or for actors to play, a sweet sin to write about. But what about rapture, tranquillity, the contentment we all seek? Happiness writes white, goes the phrase.

I asked half a dozen people who write, who the heck said that? And I finally came up against a passage from Martin Amis' "London Fields," an unreliable narrator offering unreliable insight within their miserable purview: "I think it was Montherland who said happiness writes white: it doesn't show up on the page. We all know this. The letter with the foreign postmark that tells of good weather, pleasant food and comfortable accommodation isn't nearly as much fun to read, or to writer, as the letter that tells of rotting chalets, dysentery and drizzle. Who else but Tolstoy has made happiness really swing on the page? When I take on Chapter 3... I'll have to do, well, not happiness, but goodness anyway. It's going to be tough."

I won't compare Crowe to any page from Tolstoy, but there is a line late in Almost Famous that sounds smack-worthy on the page, yet in context, performed, it is filled with goodness and hope and does not belong in a moment so fragrant with the potential of death and demolished youth. It's tough. Tender; tough. A central character earnestly in need of a stomach pump, being kept awake until a doctor arrives, burbles, babbles, and comes out with the line, "I'm all about the positivity!"

And so is Cameron Crowe. In Almost Famous, green, baby-faced William Miller aces several assignments, then, without having met the young scribbler, is given a Rolling Stone assignment that could become a cover. He's sent on tour with apocryphal arena rockers Stillwater, fronted by one Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup, reserved yet watchfully taking it all in), who is antagonized by another member of the band, Jeff Bebe (Jason Lee, funny and focused) for stealing his glory. What William does with this story will affect the course of his own career, but also the career of the band, and he will find first love in the gleaming, angel-haired person of Russell's greatest fan, Penny Lane (a luminous, tough-but-easily-damaged Kate Hudson), one of several "Band-Aids," a clutch of groupies with better-than-average manners who follow Stillwater. Crowe's knack for casting has not failed him yet: Brad Pitt, his first choice for Russell, could have toppled the movie's balance, making his scenes more sideshowy, where Crudup does not; and even actors who are obviously meant as caricatures, such as the double for Rolling Stone's publisher Jann Wenner, fit snugly into their scenes.

Fugit's performance, a charming and inspired one, channels the wiles of a young writer. Fugit has a way of swallowing lines but still making himself crystal-clear. His large eyes, following the ways of this world he has only known through records, brim with curiosity but also the necessary discernment, even judgment, of the born scrivener. There are several terrific scenes with Philip Seymour Hoffman (let us not spend words, but only bow deeply in his direction) playing Crowe's real-life mentor, the late, vital rock writer Lester Bangs. A café scene where Bangs lays down the law, the rules, the doctrine, to this callow child is an instant classic. Then there are their phone calls late at night, William seeking the light, Lester offering sage, heavy-voiced brilliance about the ways of rock and more importantly, the ways of rock musicians, the two chatting as if they are the only two people awake on earth at that very moment.

Crowe keeps himself awake between movies with another habit of the born writer: procrastination, or taking on other tasks to avoid tasks at hand. A practiced interviewer, Crowe is also a giving and forthright interview subject. Meeting him before this week's debut at the Toronto International Film Festival, Crowe told me about how Billy Wilder, Crowe's idol and the subject of his essential book, "Conversations with Wilder," viewed the idea of Almost Famous. "I kept trying to audition ideas for what I was working on and he would have None. Of. It.," Crowe says.

"'These personal movies, they are garbage! Who cares about such a thing? Next question.'“ What if it was about you as a young journalist in Berlin?' 'Even more boring. Who cares? Maybe your mother and father, mine are dead, next!'"

Crowe laughs with the memory. While commercially successful and respected, Crowe takes a lot more time than a director like Wilder between projects. What took so long: False starts, many drafts, doubts, permutations, finding the core of the story? "All of the above. I avoid rewriting by writing. Sometimes whole new things. Where you write yourself into a corner almost so you give yourself a break and you don't have to write. Or the other thing is to hit a wall and then torture all your friends and family and loved ones with Hamlet-izing, which I am really big on. "Why am I doing this? What is the point? Let's speak objectively! Let's forget we've had this conversation a hundred times before, let's just make it all fresh, come to it fresh right now, should I really be doing a movie about sort of my own experience?' And then my wife, for example, would be like, "Okay. Coming to it fresh..." Crowe grins, even giggles at the memory. "'Yes. You should do it. You've got to put away those boxes with artifacts that you've never been afraid to throw away.' Okay, okay, I say, and then the process repeats itself. Basically someone has to rip it out of my hands."

Is that doubt or has that become process? "It's become process. That's really well-said. It's doubt that's become process. If I remember that, it might save me a couple days at least. But it's true. It's indulgent to make that part of your process. I really want to work on a faster basis."

But you've been a professional writer for how long? "Too long. Too long to have these problems." I cite Neil LaBute's version of a writer's need to bang up against deadlines: "If you really needed it on Monday, you should have told me, so I could have started it late on Sunday night."

"That's right, " Crowe affirms. "That is how it works. I'm working with someone now who wants to start my next movie in November [Vanilla Sky, with Tom Cruise, Penelope Cruz and Cameron Diaz], and they're going to allow me the opportunity to make this story that I love and believe in, but mostly I like the idea of picking up the pace because I've always taken so long. This [producer] thankfully knows to just stay on me, 'We cannot [start] any later than November 3, or it doesn't get made. It's a window where we can do it. And I'm going to make it. Simply because the whip is cracking in the right way."

Crowe pauses, then demonstrate the enthusiastic gratitude for experience that characterize both his films and how his co-workers describe him. "The whole thing is a privilege. It's fun to talk about the funny little ways of process, but overall, y'know, I'm very lucky to be here. If people hadn't have liked Sean Penn as Jeff Spicoli [in Fast Times at Ridgemont High] I would be doing something else. I would be a DJ, moving around the country, trying to find a radio station that would keep me for a while. That's the truth of it. I got lucky early and didn't put a string of failures together that was long enough to keep me out of the arena."

So Almost Famous isn't his pet project, taking advantage of all the goodwill earned by the massive success of Jerry Maguire? "I think my alarm system is good enough to have stopped if it was going to be like that. I have a real problem with bottom-of-the-drawer scripts or the pet project that you must endure. I don't know if Billy ever did one, but the thing is that there is that musty indulgent feel that comes with projects like that. I never wanted to do that. It was more like I wanted to do the movie that answered the question of what it was like back then. I used to feel bad that I had never gone to prom or things like that and then as time went on, I came to realize that I was lucky, I was lucky to have been on the road with Led Zeppelin.

“Now biopics are coming out about people I used to interview. It's like, 'Who's that guy you've cast? I was there! It did not look that way!' I wanted to do the movie that captured the way I remember it. I'm lucky enough to have gotten close. With [cinematographer] John Toll's help, I was able to do it in a way that made me feel it was all worthwhile and I'm not just dragging people back through my memory bank, like, 'Ah, the glory of my youth!' But it's great when that bus takes off [in one scene] and you're hearing 'That's the Way' by Led Zeppelin and there's a flare [going off]. It's the kind of moment that I remember and it's good to have it up on the screen. So yeah, I wanted to use just a little bit of my credit line, but to do it right."