The Film Center in Chicago is featuring Robert Altman for his centennial, and for Newcity, I spoke to programmer Rebecca Fons about her Iowan affinity for the films of the prolific Missouran and also drew on several interviews I had with him in the last decade of his life. (It’s Newcity’s May film feature in the magazine and online here.)

Altman’s clear Midwestern voice, Fons told me, “gave him the talk to make films that American audiences from coast to coast saw themselves in. His grand cast of characters were an assemblage of us: all the good and gnarly parts of Americans; the highs and the lows of life; the sweet and the sour of any given interaction with a lover or a stranger. By being from smack dab in the middle of the country, Altman could see us all from a 360-degree view, and then tell it like it is.” That full piece is here.

I grew up on a couple-acre patch of green amid rolling farmland in the west of Kentucky—I spent eighteen years there one week, the tired joke goes—and didn’t grow up with movies. I grew up among people. People who talked. And talked. Stories were everywhere. Histories were spoken aloud. Women and men in their eighties and nineties who had sat on the lap of Civil War veterans when they were small. Legacies were alive. Everyone knows and trusts implicitly the basic, indispensable relationships and alliances and mutual associations in a town of a thousand. You’re forced to, through fires, floods, illness, economic slumps. Cemeteries were filled with the names of people you knew who were the successors of the passed. A dozen identical headstones would answer to the same name.

One night, young, I saw both “Nashville” on a big screen and “The 400 Blows,” uncut and uninterrupted, Janus Films logo and all, on late-night PBS. And that was it. There was a path in the darkness ahead, like through the thicket across the way. Many movies followed. Stories—movies—still hold weight for me in the smaller, smallest details, such as every aspect of the final, chilling, thrilling shot of young Jean-Pierre Léaud’s face at the end of “400 Blows.” Truffaut described similar vivid details, glimpsed only by the viewer in solitude with a character, as “privileged moments.” (“The 400 Blows” is one extended privileged moment.)

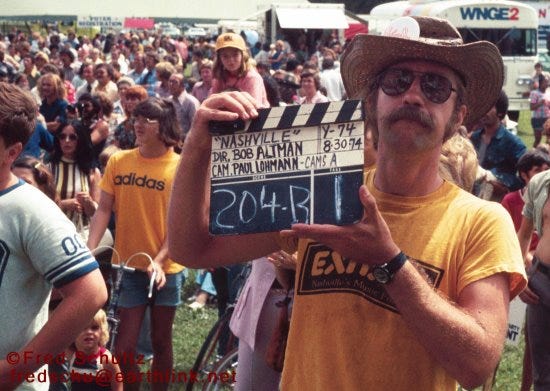

Robert Altman’s 1975 tapestry for all time, despite elements that were called out as inauthentic to the music metropolis of Nashville in its moment, weaves twenty-five characters (including the disembodied voice of a folksy populist presidential candidate spieling from a passing campaign van) in as dense and heart-stopping a critique of American horseshit as you will ever see. The politics of the 1970s and the blather that “don’t worry me” and the fear of sudden moments of violence, ring down the half-century. Radical endings, both. Beginnings for me.

With “After Hours: Scorsese, Grief and the Grammar of Cinema,” Chicago-based writer Ben Tanzer uses the movie that changed Martin Scorsese’s life and career in 1985 when he was flailing, to circle, in prismatic fashion, his own creative life. Tanzer takes up the warm legacy of his artist father and therapist mother; other writers who have influenced him, like Jim Carroll as well as music of a time; late nights in New York at the end of the century; and of course, “After Hours” and the thin-lipped smile it would have brought to Kafka’s lips. Tanzer finds a personal way into the “essay-ella” form from series like “33 1/3,” and we talk about all of that, and more. The 3,400-word conversation is at Newcity here.

You sound like you had a great relationship with your dad, including through art, especially movies. Had you already seen Scorsese as an artistic father? Did you need to recognize artistic fathers, either personally, or for your ongoing work?

My dad and I did have a great relationship, and it was complicated by the challenges he faced. He really loved art and movies, though, as did (and does) my mom, and he was a proud Jew, New Yorker, activist and mostly reformed tough guy. Scorsese was important to both my parents because they saw him as the first American director; they watched him capture the greatness of the foreign directors they admired. For my father it went deeper too—Scorsese was the first director who captured what he felt about the New York City he grew up in: poor, violent, insular and full of hustlers. I don’t know that Scorsese is an artistic father to me; he is, however, wholly integrated into the series of inspirations—and there are many, for how I want to see and capture the world myself.

I wrote about “Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors”, Ian Penman’s essential rumination of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and how his cultural life crossed that of the German dramatic polymath in the early 1980s, when it was published two summers ago.

A commonplace book of fractions, reflections, refractions of a demiurge: Penman is willing cataclysm in finely forged bursts, some macro, some micro, minted as gleaming coin: “Life lived at a hurtling rate: beyond a certain point impossible to tell whether it’s speeding up or skidding down or whether finally these now amount to the same thing.”

Writing about movies isn’t exactly the same as music being “dancing about architecture,” as comic and painter Martin Mull put it, but the concrete fact and the elusive allusion of the audiovisual form is usually taken up in essays of variable length and oral histories and coffee-table books.

Penman cites the Fassbinder canon of influence, led by those he adapted—Alfred Döblin and Vladimir Nabokov—and those he ably aped, like master melodramatist Douglas Sirk. But his own book is collage, or bricolage, a term popular when Penman first encountered art high and low, a life captured in the fashion of a literary compositor like David Markson (“Wittgenstein’s Mistress”).

“He is not an exquisitely doomed wit or decadent or dandy. He is rough and ready and grand and grimy and loudly specifying and spilling out all over the sides. How does this line up with the ‘artificial’ aesthetic at play in so much of his work?” Penman writes, hoping to reconcile a life with so much lyrical sorrow. (More here.)